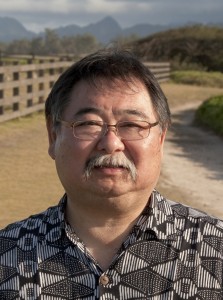

Garrett Hongo was born in the back room of the Hongo Store in Volcano, Hawai`i in 1951. He grew up in Kahuku and Hau`ula on the island of O`ahu and moved to Los Angeles when he was six, much to his everlasting regret. He complained so, his parents sent him back when he was nine, where he lived in Wahiawā and Waimalu with relatives who so hated him, they stuffed him on a plane back to L.A. when he was ten. He grew up fighting from then on, all the way through Gardena High School, where he encountered Shakespeare, Camus, and Sophocles in English classes. They convinced him to try higher education, so he went to Pomona College, managed to graduate, still fighting, and found poetry there under the tutelage of Bert Meyers. He wandered Japan, Michigan, and Seattle thereafter, supporting himself through wits and lies, directing the Asian Exclusion Act from 1975-77, becoming poet-in-residence at the Seattle Arts Commission in 1978. He then gave up wit and went back to graduate school at UC Irvine, studying with the poets Charles Wright, C.K. Williams, and Howard Moss, all of whom averred he deserved hanging. Hongo has subsequently taught at USC, Irvine, Missouri, Houston, and Oregon, where, fool that he was, he directed the MFA Program in Creative Writing from 1989-93. He has written three books of poetry, including Coral Road (Knopf, 2011), edited three anthologies of Asian American literature, and published a book of non-fiction entitled Volcano: A Memoir of Hawai`i (Knopf, 1995). Not among the falsehoods on his resume are two fellowships from the NEA, two from the Rockefeller Foundation, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Lamont Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets. He is now in semi-retirement and fights no one, having lost all his teeth and suffered from tapioca of the hands. He plays with his daughter, scolds his two grown sons, and loves his wife Shelly Withrow. He is presently completing a book of non-fiction entitled The Perfect Sound: An Autobiography in Stereo. In Eugene, where he lives, they call him, among other things, Distinguished Professor of the College of Arts and Sciences and Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Oregon.

***

LR: As a longtime professor of creative writing at the University of Oregon, what has the relationship between academia and poetry been like in your life?

GH: Academia has provided a space for poetry, actually. We can pursue it seriously this way—in formal classes and workshops. I didn’t fully and consistently connect with my own poetry until I got to an MFA program—at Irvine—where I studied with C.K. Williams, Charles Wright, and Howard Moss. They each gave me something different that I desperately needed—C.K. a big push and a challenge, Charles subtle and constant support and a craftsmanlike approach in answering my own inspirations, and Howard amazing formal wit and geniality in working with my own poetic structures. Since then, as a teacher myself, I try to do things similar for my own students. The poetry workshop has been a haven, though, a place to put the busyness of the world aside and concentrate on poems, poetic thought, the imagination. Academe has been the environment that has supported this most consistently for me.

LR: In your writing, geographical and cultural landscapes have inspired both poetry (e.g., Yellow Light, The River of Heaven, and Coral Road), and prose (Volcano: a Memoir of Hawaii). How do you switch gears from one genre to the other?

GH: It’s not easy, actually. I took years and years to find the prose style for Volcano. I wanted a dense, even a cadenced prose like Melville’s in Moby-Dick, a storytelling one like Thoreau’s in Walden, and a “poetic” one like Emerson’s in his essays. My other models were Kamō-no-Chōmei’s hojōki (translated by Oliver Sadler as “An Account of My Hut”), a kind of Book of Job in Japanese, tsurezuregusa by Yoshida Kenkō (meditations on life and aesthetics translated as Essays in Idleness by Donald Keene), Petrarch’s “The Ascent of Mount Ventoux,” and Yasunari Kawabata’s izu-no-odoriko (The Izu Dancer), a kind of Japanese La Vita Nuova.

You notice only the Kawabata is contemporary? It’s the flaw of the book for general audiences, I suppose, but I wanted to see if I could create a prose that was like poetry. The poet Mark Jarman in The Southern Review likened the book to Wordsworth’s The Prelude, which was a huge compliment and another book in the back of my mind as I wrote. It indeed was about the growth of my own poetic mind, to see if I could, like a python, dislocate my poetic jaws and swallow a huge and gorgeous landscape, all those ostensibly non-poetic subjects like geology, volcanology, rain forest biology, oral family histories, and local talk story. I’d felt my own poetry too confined to take on that Volcano world, so I turned to prose, but not a prose of reportage or standard non-fiction. It had to have the weight of meditation, aimed for the capture of fleeting insights and inspiration like poetry.

After I turned the manuscript in, I was working on revisions and edits with my editor Sonny Mehta. He wanted complete concentration on the project, so we met in his suite at the Bonaventure Hotel in LA for two whole days. The first thing he said to me was “Garrett, now I know why you took so long to turn in this book. It’s not prose, is it?”

It took me a long time, though, to come back to poetry, as my inner identity and voice had been completely altered by the experience of having written Volcano. Some count it as a 23-year long “absence” or silence between The River of Heaven and Coral Road. Chronologically, I suppose it was. But really, what I was doing was adjusting to the new thing I’d found and staying silent about other things I found completely unpoetic in my life—the loss of my first marriage, raising my sons as a bachelor father, accommodating to the quiet regional life in Eugene, Oregon. When I did adjust, when I found a new life with Shelly Withrow, I spoke again and out came Coral Road, which I think is a natural progression from the lessons of Volcano and The River of Heaven, a natural extension of the prose and poetic voices in both.

I’m working on three projects now—one a book of non-fiction about my audio hobby; a new book of prose poems about Los Angeles; and an extended narrative work about a Nisei G.I. at the tail end of WWII and thereafter, studying painting in Florence, Italy. Of the three, only the audio book might actually be in “prose.” The others are very poetic.

As far as landscapes go, they’re a trigger for me, a big part of the magic, if you will, of falling in love with things and speaking poetically about them. I can’t be happy unless landscape is in there. I’m kind of a landscape painter in that sense, like Paul Cézanne or any plein air painter. I love description and can’t write without it. That’s why you see landscapes, cityscapes, and seascapes in my work all over the place. It’s how I start the work of seeing, of being in love with a subject, of being loyal to its feeling.

LR: You have described Coral Road as “a book about travail” and “a song of woe” that dramatizes the unique “dual immigration” experience of Asian Americans who move first from Japan to Hawaii, and then to the mainland after the sugar economy collapsed. What I find particularly interesting about these stories of the Hawaiian diaspora is the way in which discourses of authenticity emerge that imply greater questions about the nature of cultural identity. Could you speak more about some of the writing choices you made when deciding how to best frame these issues in the book?

GH: Do “discourses of authenticity” automatically imply “greater questions of cultural identity?” I don’t think so, actually. I think they tend to shut down the greater questions of cultural identity. In fact, that’s what “discourses of authenticity” are indeed structurally designed to do. Think about the Black Arts Movement, for example. For all its contribution to black pride and the renaissance of African American culture, one of its goals was to shut down, put down, and quash the diversities of cultural identity within African American literary production, identifying, branding, if you will, writers like Ralph Ellison and my own teacher Robert Hayden as “Uncle Toms” and “Negroes” who were too accommodating to white cultural dominance and too learned regarding Western canonical literature. Had Gwendolyn Brooks not embraced the doctrines of the Black Arts Movement, she too would have been denounced and ridiculed for her being so practiced in traditional English poetic forms and diction. I knew Robert Hayden and was shocked when he explained how he was considered persona non grata by black students at the University of Michigan because his poetry had been so branded. It was a disgraceful way to treat the author of “Those Winter Sundays,” “The Middle Passage,” and “El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz (Malcolm X).” History creates these self-identified movements of “authenticity” as much to stifle as to empower. “When the power shift to their side,/I wasn’t black enough for their pride…” writes Caribbean Derek Walcott in his great poem “The Schooner Flight.” When I read that, I knew and felt deeply what he meant. “I’m just a red nigger who love the sea,/And either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation.” Partly because of his hybridity, his mixed-blood and culture, Walcott’s Shabine, the sailor who loves the sea, is outcast within the contemporary nationalist movements of the Caribbean, made an exile from his own homeland. I know that feeling, being an outlier myself.

My basic take is that there are very serious contestations going on regarding indigeneity, hybridity, diaspora, and naturalization to the landscape of Hawai`i. Most writers and scholar/critics have sought legitimation and created discourse at the level of “authenticities” with regard to representation, canceling and vying and seeking ethical, political, and moral certainties. This discourse that was created and now dominates acts as a kind of policing mechanism, therefore, suppressing other diversities of discourse, disciplining existing discourse into the categories set by these policing discourses—e.g., legitimacy, local, Native Hawaiian, outsider, etc.

Under this mechanism, I would qualify as an outsider—the “Mainland,” California, West Coast, or “kotonk” author many of the self-proclaimed “local” writers would label me as. Under the discursive mechanism of indigeneity as value argued for by writers like part-Native Hawaiian Haunani Trask and Japanese American scholar-critic Candace Fujikane at UH-Manoa, I would qualify as a “settler” writer akin to South African descended from colonizing Boers—the Dutch.

However, both these discourses fail to account for history—immigration, migration, and diaspora. My ancestors did not come to colonize Hawai`i as the Dutch did South Africa, nor did they STAY to colonize Hawai`i as Trask and Fujikane say the emergent Japanese American bourgeoisie did. In fact, my family was dispersed in a subsequent diaspora FROM Hawai`i, as the days of King Sugar ended and its laborers had to emigrate once again in order to survive. My family re-settled in Los Angeles, where I grew up from the age of six.

But my early childhood in Hawai`i is no less legitimate than any local writer’s childhood. It’s just that I see it through a different lens—not one of naturalizing myself and my ethnicity to the landscape of Hawai`i, but through the lens of a kind of literary Romanticism, in fact, and also a theoretical awareness of hybridities, diasporic nostalgia and loyalty, and a consciousness that is as much cosmopolitan as regional.

What’s not discussed is that there is a diaspora of displaced peoples FROM Hawai`i—Native Hawaiian, Japanese American, Korean American, Portuguese, Puerto Rican, Chinese, hapa-haole, and haole. We cannot be explained, as the policing discourse would explain us, by the label “outsider” quite, as we have histories and attachments to the place completely unlike mainstream tourists or bourgeoisie professionals who come to buy real estate and settle in Hawai`i. Our connection cannot be denied, nor do I wish to displace the claim of any other of the “legitimate,” local, or Native Hawaiian voices that claim they are the essential voices of Hawai`i who should be heard. Not at all.

Yet, I understand how I am perceived as a threat. It’s a shame, but, in a material sense, it is about competition for various forms of recognition—within the local scene, state funding, mainstream publishing. I’ve been lucky that way—in terms of publishing, that is—but it’s not my fault. I had no trouble from the Bamboo Ridge group until I published with Knopf. The fear and anger, I think, come from an anxiety that a single voice will be chosen by the system, already seen as oppressive and discriminatory, the episteme, if you will, as “representative” without election from the region that voice might be (mis)taken to represent. In that sense, the issue has to do with systemic over-simplification and the over-simplified, angry reaction engendered in those who perceive themselves as silenced by that initial over-simplifcation that has selected an “exemplary and representative voice” without input and participation from those silenced and marginalized by this episteme.

When Frank Chin came out with his angry response to the widespread acceptance of Maxine Hong Kingston‘s work, his accusation was she was “fake” Chinese and promulgated stereotypes and a narrative of assimilation into the mainstream, white world. To me, what was more interesting than the accusation was the creation of distinctive, exclusionary, and fundamentalist categories of “the real” and “the fake.” I’ve already written about this in my Intro to Under Western Eyes, my anthology of Asian American non-fiction. I also wrote against nationalist unisonance as a reactionary myth in the Intro to The Open Boat, an anthology of Asian American poetry, in which I tried to argue against a qualifying politics and for diversity—political, aesthetic, cultural, and even ethnic—within the category of AA poetry.

Moreover, there are also at least three other ways to respond to assumptions about authenticity vs. usurpation of that space by “the fake”:

1. My ghosts are in Hawai`i—my father and paternal grandfather in Volcano, my maternal grandfather and grandmother on O`ahu. While my grandmother was still alive—she only passed away two years ago this April (a month shy of her 102nd birthday), I went back every year to visit her on O`ahu. Indeed, she was my fondest connection to the past, especially to Kahuku and Hau`ula.

2. There is a trajectory of blame and scapegoating, a pharmakos, if you will, in the practice of condemning various writers who write of Hawai`i as “illegitimate” and “outsider,” as though these acts, cathartic though they may be, could cleanse the collective guilt we all feel for the injustice and criminality of the land being colonized by non-Hawaiians. These condemnations and vilifications are almost ritual, marking intruders and interlopers, branding them, excluding them on the order of Oedipus being cast out of Thebes as a poisonous presence. The arc of the activity and its passionate performances are psychologically and sociologically beneficial to the performers, identifying them as a “tribe” of authority, indeed in a mimetic fiction of tribal origin in ritualized difference, and casting out non-tribal identities and entities in acts of self-valorization.

3. Nationalisms identify a narrative that there is both a history and an imaginary contemporaneity that are held in common by a group, that those not holding to this narration or bearing its marks are outside the nation. Whether one shares the history is nearly meaningless as one must also dwell in the imaginary contemporaneity as well—in other words, be in sympathy and communication with those who identify themselves as that nation. Deviations, particularly those that advance any competing or more complex narrations, are suspect, threatening, and potentially invalidating of the narrative of the nation. I think this is one difference between the positions/perceptions of Wole Soyinka and Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

LR: In crafting the poetic representations of history that constitute the poems of Coral Road, how did you take the historical source material you gathered to an imaginative poetic space?

GH: I wrote Coral Road as an homage to my mother’s side of my family, the Shigemitsu and Kubota who worked as contract laborers on the North Shore of O`ahu in Hawai`i during the early part of the 20th century, after arriving there as immigrants from Southern Japan. They were a tough, stoical lot, marrying themselves to hard lives on land they occupied for three generations, rootlessly, as the land was never theirs and could never be. They were there for reasons of history and diaspora—the land belonging to capitalism or the lost Kingdom of Hawai`i. What I have of our time there are fragments of stories, songs my grandparents sang washing dishes, a meager handful of documents and a few phrases in Hawaiian and Japanese, and the sparkle of the sea or on the tassels of sugar cane as I drive by whenever I take a survey of those old seaside lands along what is now Kamehameha Highway. I am not a native son nor prodigal one, consequently, but a kind of swallow who has lost his mud home on an island thought by so many to be a paradise.

The people in this book are the legends from my childhood—my grandmother who walked, as a twelve-year old and by night, 25 miles along coral roads and railroad track from Waialua Plantation to Kahuku so she could escape a bad labor contract, her path lit by the moon as she made her way in secret as a runaway; my uncles who fought for America in Europe during World War II, while a family elder was taken from Hawai`i and spent the war years in a DOJ detention center in Arizona; my father, who brought back from Italy and his time in military service an affection for Renaissance painting and American Big Band music. And I am there too—a fourth-generation American hankering for these lives to be known and celebrated, for the music of my language to sing of them.

The historical source material? Just that—as grout and stone for the imaginative seawall I was building to protect my house of histories and mementos from being eroded by time. They undergird the stories I’d already inherited or gave me clues to pursue other stories, all of them part of the matrix of feeling I’d built up, my wish to pay homage, my wish to claim my own descent from that history and that place that has become so different now, even from my own childhood past.

The quick thing to say is that the book is about “heritage” where there is no legacy except love and memory.

LR: You have spoken of your unwavering poetic interest in origin, descent, cultural specificity, and the notion of the imaginary homeland. Where do you think this interest comes from and what techniques have you employed to represent it in your poetry?

GH: I think it comes from having been uprooted at a critical age—six—and then “returned” twice: once when I was nine for a summer in Wahiawā and 5th grade in Waimalu; then, when I was nineteen and I came back to Hau`ula and Kahuku for a winter vacation in the landscape of my childhood. Feelings were released in me I didn’t realize I had—”a great ache,” as I say in the poem “Kawela Studies” about that return when I was nineteen. And the stories I kept hearing pieces of each time I returned—the family stories, very gothic ones, and tying them to other oral histories and the general history of Japanese plantation workers in Hawai`i as more and more scholarly work got done and published.

I have to give thanks to both the storytellers in my family—my grandmother Tsuruko Kubota, my grandfather Hideo Kubota, my aunt Sawako Sanjume, and my cousin Leanne Sanjume—all of them gone now—and to the historians and scholars of this history—Warren Nishimoto and Michi Kodama of the Center for Oral History at the University of Hawai`i-Manoa, Franklin Odo recently retired from the Smithsonian, and Ronald Takaki at UC Berkeley (recently deceased). They all helped me, encouraged me, released my imagination into the scraps and shards of stories about the plantation past so that I could occupy the interstices between them with my own lyricism and make of them a continuous feeling of loyalty, love, and homage.

As far as technique goes . . . I’m not sure I can answer that so easily. I think about things a great, long time before I compose. I wander the landscape, gaze out over the seascape in Kawela, Kahuku, Hau`ula, walking along the beaches and promontories. I tell myself these stories each time I pass a stand of ironwood trees in Kahuku, every time I pilgrimage to the Japanese graveyard in Kahuku. I try to live in them, you see. Then, when it’s time to write, I write—bringing to bear all I know of these histories and stories, as though they were the myths of my literature, and also bringing to bear all I know of poetry, the history and techniques of poetry in English, and the poetry of the world too as I’ve come to know it. That’s why, in Coral Road, you see Kubota writing to José Arcadio Buendía from One Hundred Years of Solitude, to the Spanish poet Miguel Hernández and the Chinese poets of Angel Island. Why you see the Nisei G.I. I call Fresco painting scenes of plantation life and the 442nd in WWII through what he’s learned from the tradition of the Italian Quattrocento. Traditions in poetry and painting are things I know something about, so it’s my habit to derive from them too—from the Wordworthian verse paragraph in The Prelude, from the extended Whitmanic line, from Ezra Pound’s imagism and rhetorical complexity. It’s just there for me in my training and part of what workshops call “my voice,” so I write easily this way when I do write. But, the big thing is to have what to write in terms of subject and feeling and sweep of imagination. Technique is always there.

LR: The second of the five sections in Coral Road entitled “The Wartime Letters of Hideo Kubota” consists of epistolary poems that challenge the politics of WWII, which America largely regards as the touchstone of just war. Written in the voices of Americans whose loyalty to the flag is in question due to their ethnic origin, these poems also consider how subsequent generations are touched and shaped by the emotional fallout of war. It is difficult to read these meditations on WWII without drawing contemporary parallels to the War on Terror and its effects on Muslim American citizens. Can you talk a bit about how you see the relationship between past and present in Coral Road?

GH: I was just on the phone with my old and dear friend, the poet Edward Hirsch, and we were talking about just this sort of thing—how history and its devastations, its trials of the human soul, have given us great lessons that survive in the poetry from these times as repositories of human wisdom. In one of his tragedies, Aeschylus writes: “In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.” It’s this kind of wisdom Kubota seeks when he writes to his chosen sages in poetry—the Turkish poet, a Communist, Nazim Hikmet, who was imprisoned by his own government for sedition; to Tadeusz Różewicz, the great Polish poet of post-war reconstruction who came back to a country both physically and psychologically devastated by war and created a poetry of simple human values, direct statements, and blunt-force love. He invokes their spirit to both console and counsel him through his own travail and isolation, a detainee in a Justice Department camp. He reaches out and conjures their spirits to lend him their wisdom, their patience, and their resolve to continue—to prevail, as Faulkner said.

I write so much about the past because I wish to be its child. I look upon the lives and spirits of my grandfather, Hideo Kubota, and father, Albert Hongo, as exemplary. To me, they were Titans who walked the earth, who fought through an elemental history in order that I could be their mortal son. I want to pay them homage, I want to live up to them, I want them to welcome me in heaven when my time comes. Despite the distractions and beguilements of the contemporary world—Calypso’s spell—I want their past to live in my present and to guide it. That’s how I try to live, how I try to write.

LR: Do you have a specific routine that you like to follow when you sit down to write? If so, could you describe it for us?

GH: Yes, after I’ve committed to composing a piece, whether extended or short, I simply sit down after breakfast and coffee and pick up a note from my notebook, whether it’s a collection of images or another kind of composing idea or narrative situation, and I begin writing. Usually, the style comes out pretty easily, as I’ve worked all that out before I commit to composing. I “hear” a voice, in other words, in the back of my head—”a chune,” as Yeats said. For example, in “The Wartime Letters of Hideo Kubota,” I knew which poets Kubota was to address and which of their poems—”Lullaby to an Onion” by Miguel Hernández, for example, and the situation of him in a Fascist prison near Madrid. Kubota himself was locked in the stockade of the trading post in Leupp, AZ on the Navajo Nation near Flagstaff on the Mogollon Plateau. I had these facts, these situations, and I simply wrote. The poem came out in one day from first draft through about three revisions from notebook entry, some re-worked lines, then to typescript, back to lines revised over the typescript and written by hand, then another typescript revision. And so on. But, to arrive at that point of composition took, I’d say, years. I had the idea of an AJA detainee at Leupp for over thirty years, having visited the place my freshman year in college in 1970. I knew Hernández’s poem for almost that long and his plight, having received a letter while he was in prison from his wife who said that they were starving, having nothing to eat but onions, that even her breastmilk for their infant son must taste of onions. And I knew from stories Wakako Yamauchi had told me of AJA farmers during the Depression having nothing but carrots to eat what that must be like. Finally, I’d dramatized the situation for myself in my own head—a sequence of poems from Kubota to these world poets who’d suffered detention and then release: Nazim Hikmet, César Vallejo (poem uncollected), the Chinese poets of Angel Island, Pablo Neruda, Tadeusz Różewicz, and others. Finally, though I’d planned for Kubota to address Czeslaw Milosz during the days after returning from WW II when he wrote “Dedication,” I hit upon José Arcadio Buendía tied to a tree from Cien Años de Soledad and Charles Olson‘s “Maximus, to himself” and “Maximus to Gloucester, Letter 27 [withheld]”to fill out the sequence. Those situations filled out the “stages” of Kubota’s struggle, if you will, his progress from forlorn and emotionally abandoned detainee to returnee and a new citizen of his village on the North Shore of O`ahu.

The poems arrive from my feelings of yearning back so long ago for a history, a people, a story, our AJA and Asian American identities having suffered without foundational epics, narratives when I was a kid growing up in Hawai`i and L.A. I wanted this for myself, for the people I loved whom I’d witnessed, I thought, abandoned by history. And they arrive from my learning in literature, from my having created a cadence and a diction for my own poetry. Finally, they arrive from imagination—dreaming all these things together is the process that makes the poem begin.

The routine is nothing but routine I guess, it’s very special and more like a sort of ritual after I’ve gathered all these other things up—more like an actor’s performance after having built a character and placed him in a narrative situation. In this way, my poems are like an actor’s takes for the camera, except mine are for the page.

LR: After writing three books, what’s your secret for keeping your poetry fresh?

GH: Hah! Maybe it isn’t! I mean compared to what younger poets are doing, my stuff is pretty traditional, I guess. I’m not trying anything new or quirky or post-modern, not sampling or incorporating collage or rap or talk radio or graffiti. I’m going back to AJA history, British and American Romanticism, and the world of hope poets speak from internationally in the face of oppression and war. Harking back is what I do, I think. So “fresh” isn’t a value for me so much as depth, yearning, and a vision backwards glancing through history.

I invent situations, though, characters like Kubota, Fresco, and my old shakuhachi maker from Yellow Light. I’ve characters I’m collecting now—based on Nisei artists in LA’s J-Town and Chinatown just before WWII, based on a Nisei G.I. studying painting in Florence just after WWII, a Sansei based on the kabuki character from the play Sukeroku, and the like, a Sansei singer for a rock band based on an amazing woman I used to know whose family ran a restaurant in J-Town. I put them all in a bar in J-Town in the Fifties and Sixties. These are for my next book, all about AJA life in LA, and kind of centered around music and painting, musicians and painters.

LR: In 1993, you edited The Open Boat—a seminal anthology of contemporary Asian American poetry. What led you to compile such an anthology at that particular time? In your view, how has the position of Asian American poets within the landscape of publishing changed since then, if at all?

GH: Well, that’s a question with many answers, to tell you the truth. I decided to do it, again, mainly because I was tired of the Asian American critics, such as they were, dominating the interpretive reception of Asian American poetry, claiming it was one, lock-step, proletarian-based and anti-hegemonic protest against The Man. In the early 90s, I’d been invited to an Asian American literary conference at a major West Coast university—the first one in years, although I’d been part of the first AA lit conferences back in the 70s—and was appalled at the hammerlock on open interpretation of the poetry these critics were executing and among so many of their college and university students. Granted, the mainstream hadn’t yet quite awakened to the presence of Asian American poets as a “collective,” but these Asian American critics hadn’t yet awakened to the principle of diversity and inclusion—aesthetic, political, ethnic, and regional. I write about it in my Intro to The Open Boat (and give more specifics, I might add). And, I felt, they were actively silencing this diversity. This reminded me so much of the work of what playwright David Henry Hwang has called “The Gang of Four” in their attempts at gate-keeping through their anthologizing, essays, and back-stabbing—they acted and functioned like a literary Mafia, condemning any outbreaks from the party line they issued, publicly denouncing single writers. What struck me was here, at this literary conference, there was in play another serious attempt at “licensing” the category of Asian American literature by a cadre of like-minded, politically narrow thinkers. I really didn’t like that.

I wanted to open things up because I knew that Asian American poetry was this huge spectrum of practice, from the activist and consciousness-raising work of Janice Mirikitani and Lawson Fusao Inada to the avant-garde work of Mei-mei Berssenbrugge and John Yau. I knew there were South Asians like Chitra Divakaruni and Agha Shahid Ali and multi-racial Asians like Ai, Yau, and Mei-mei practicing poetry. And poets like Arthur Sze practicing a highly nuanced, sophisticated lyric that had to do as much with human consciousness and linguistic play and reverie as any ethnic identity. These were poets I felt fell outside the descriptive category of “Asian American” as defined by the academic critics and students I was meeting at the conference. I wanted to include those who fell outside that narrowing descriptive category. I wanted an “open boat,” if you will.

I also wanted to introduce our poetry to a wider audience. To ourselves: those Asians out there who were yearning to hear from us; those in the mainstream who would welcome new voices, welcome the diversity we brought to America singing. That’s why I lobbied hard to include photographs in the anthology—because I knew we’d look so striking and handsome. And I wanted a book of us and for it to come from a major press that could not be ignored. Because of Martha Levin, then Publisher (who much later became Chitra Divakaruni’s first fiction editor), I found that in Anchor Doubleday.

Finally, I did it because I could. A lot of opportunities came my way after The River of Heaven came out, and this was a project I thought up myself and believed in. Publishers were really willing to get behind a lot of things I’d propose, but this was the project closest to my heart. And that I could hire my MFA students to do the initial reading and recommendations was another benefit—Eugene Gloria, Charles Flowers, and Mary Chan all worked on surveying the field, writing short reports, and making recommendations to me. I certainly gave them leads, identifying some of the major voices and most talented emerging poets I knew of, but they did the bulk of the initial work. And Charles Flowers, who ended up being David Mura‘s editor at Anchor and later Associate Director of the Academy of American Poets and Executive Director of LAMBDA, now editor of Bloom, handled all permissions. It was fun to be able to give him that summer job.

How has the landscape of publishing changed? Well, it is more diverse, isn’t it? Famous Asian American authors are numerous now, and, in publishing itself, there are Asian American editors now, Asian American literary agents, even very exciting Asian American publishers like Kaya Books and workshops dedicated to celebrating Asian American work like the Asian American Writers’ Workshop and Kundiman. Lots has gone on and no sole entity or Mafia owns the imprint of Asian American literature anymore. Even though some may still try.

And how has the position of Asian American poets changed? Look at who’s just been named a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets—Arthur Sze. That’s so cool….

LR: Do you have any advice for emerging Asian American writers who are just beginning to put their work out on the market?

GH: First of all, I wouldn’t think in terms of “the market.” With the internet, laptop publishing, readings all the time, and e-zines, the market now is more of a scene than when I started and, in that sense, it’s much more exciting. But it’s still only a medium. You can get caught up in the scene and still never accomplish your own work. If you’ve something to say, find how to say it first—-find a place, a group, a workshop, a graduate program that can help you. That’s what happened to me. I never got so serious about my work, never was asked to take my work as seriously as when I got to the MFA Program at UC Irvine and found myself among teachers like C.K. Williams, Charles Wright, Howard Moss, and Mark Jarman and classmates like Yusef Komunyakaa, Helena Viramontes, and Carolyn Doty. And my first MFA students then too—Juan Delgado, Maurya Simon, and Paul Marion—who worked with me when I was hired at Irvine for one of my first academic jobs.

Other poets, particularly one’s elders, will insist on better work from you—work that you yourself might not think you’re capable of and you need that insistence. And elders who teach might even show you how to do it if you’re lucky. It’s what happened to me.

2 thoughts on “A Conversation with Garrett Hongo”