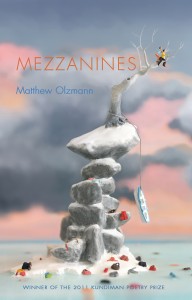

Matthew Olzmann is the author of Mezzanines (Alice James Books), selected for the 2011 Kundiman Prize. His poems have appeared in New England Review, Kenyon Review, Gulf Coast, The Southern Review and elsewhere. He’s received fellowships and scholarships from the Kresge Arts Foundation, The Kenyon Review Writers Workshop, and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. Currently, he teaches at Warren Wilson College and is the poetry editor of The Collagist.

* * *

LR: Some of the most pervasive themes that Mezzanines deals with are place, identity, and faith, all in the context of mortality. Can you talk about the relationship between mortality and some of the specific places, identities, and beliefs you grapple with in the book?

MO: I’ve heard it said that most of literature, in some way, grapples with only one question: what does it mean to be alive? I’m probably not capable of answering that question, but if the idea of mortality hangs over a lot of these poems, it’s because I often get stuck thinking in binary terms; I get at things by considering their opposites. What does it mean to be alive? Not a clue. What does it mean to not be alive? Now I’m sufficiently terrified. What I’m saying is I tend to be the type of writer who understands the dark only by flicking the lights on and off a couple dozen times. I understand the deep end of the pool by splashing through the shallow side. I know Eden is paradise only when I’m banging against the gate from the wrong side.

LR: Mezzanines is full of unlikely juxtapositions and contradictions; for example, the interplay between high literature and the intensely personal and emotional in “The Tiny Men in the Horse’s Mouth” or the pairing of sci-fi pop culture with a meditation on racial identity in “Spock as a Metaphor for the Construction of Race During My Childhood.” What are your thoughts on contradiction and juxtaposition as poetic strategies? As the aforementioned poems appear side by side in the book, can you explain how they relate to one another?

MO: I’m interested in making connections between various points, in metaphor as a device that makes something abstract more tangible. As such, I’m constantly looking at things that might not overtly belong together, and I’m trying to find correspondences among those dissimilarities.

In trying to organize the book, I initially arranged the poems a little bit more thematically: here are the love poems, the poems about identity, the poems about weird stories from the news, etc. However, those thematic clusters quickly began to feel artificial and predetermined. So I deliberately broke them up and tried to spread them out over the book, hoping those threads that were related in terms of “content” would echo and speak to each other across the length of the book rather that exist back-to-back as next-door neighbors. I began thinking of the order “tonally,” and those two poems—while apparently dissimilar in terms of subject matter—felt similar in terms of tone and perspective, both in their movement from humor to emotional crisis, and from an outward gaze to internal reflection.

LR: How would you describe the roles of humor and self-parody in your poems?

MO: There is no form of humor that doesn’t come with some kind of “target.” In this way, for me, humor can be a type of critique. I also think types of humor and absurdity—with their tendencies to disrupt the reader’s ability to anticipate—can be an interesting entrance to a more lyrical moment.

LR: Which poem in Mezzanines was the most challenging for you to write? Can you walk us through the process of its creation?

MO: While I’m not sure if it was the most challenging, “Spock” went through an unusual revision process. It’s actually the combination of three different poems. So the process of its creation was probably the most elaborate. First, I had to write three failed poems. That wasn’t necessarily “challenging,” but understanding that those poems didn’t work (and why they didn’t); realizing that those poems (all written at different times without the others in mind) were related and approaching similar concerns; imagining a way that they could be used together; and finally stitching fragments of them into a single poem took a lot of time.

LR: Along with a fair number of the poets we’ve interviewed at Lantern Review, you have spoken about the importance of risk and the tolerance of failure in their writing. Can you tell us a bit more about why you think the freedom to fail as a poet is important? How does that freedom impact your writing, and what are some of the practical measures you take in order to find and harness the freedom to fail?

MO: I think it’s a matter of having the right amount of pressure on you and your work. Obviously, I don’t want to “fail.” I don’t set out to purposely write poems that don’t live up to my expectations. But a certain amount of that is inevitable and part of the process. A baseball player in a batting cage might take hundreds of swings in one day. Obviously, he’s trying to hit each ball as effectively as possible. That won’t always happen, but each swing is part of the process of getting better.

LR: As a founding member, participant, and proponent of The Grind, what do you think writing every day gives to writers that writing less frequently doesn’t?

MO: This is closely related to the previous question, and, for me, writing every day is a way of managing the pressure I put on myself, balancing the desire to write a “good” poem against the inevitability of failure. For example, if I haven’t written something in three months, there’s a lot of pressure when I actually return to the writing desk. In those moments, I feel whatever I write has to be good, because this is my only chance, it’s the only thing I’ve written in ages. To extend the baseball analogy from above, you’ve only got one swing, then you have to make contact. Because of that specific type of pressure, if I haven’t written for a long time, I become less likely to write at all. I’ll start trying to create the ideal situation for writing: I have to have three hours of uninterrupted time, a clean desk, a cup of coffee, all my other work must be done first, inspiration, and appointment with the muse, etc. I have to make it count because it’s the only thing I’ve written. However, when I’m writing every day—even a little bit—it clears some of that away for me. If what I write is garbage, then I’ll be back at it tomorrow and the next day and the next. You write as hard and as well as you can, punch out at the end of the day, eat dinner, go to sleep, and come back to work tomorrow.

LR: What has being an editor at The Collagist contributed to your understanding of the publishing process as a poet?

MO: It’s introduced me to the work of hundreds of writers I was previously unfamiliar with. In some ways, it’s given me a sense of how large the poetry world is; I’m awestruck by the sheer volume of poets writing good poems. We can only publish a small fraction of those, and I’m constantly humbled by the energy, grace, and imaginative force of the poems out there that are trying to find a home.

LR: You’re currently teaching for a year at Warren Wilson College, a low residency MFA program from which you yourself graduated. How do you feel that Warren Wilson’ s program differs from traditional ones, and what would you suggest that writers interested in a low residency program consider?

MO: I’m teaching in the undergraduate writing program, which is separate from the MFA Program for Writers. The MFA has its residencies on campus only when the college is not in session: during winter break or over the summer. From my experience as a student in the MFA program, and based on what I know of more “traditional” residential programs, Warren Wilson offers more direct feedback on a student’s work. My first semester, I had an instructor respond (in the form of notes, line editing, and personal letters) to over 30 poems and fifteen essays I had written. Those letters were substantial. By the end of the semester, he had written over 70 pages of (typed) prose about my writing. That type of instructor feedback is rarely possible if you’re in a workshop with twelve other people and having one of your poems looked at every other week. I can’t speak about other low-residency programs, but I think one the strengths of Warren Wilson is its methodology and attention to developing the writer as a reader. A lot of people say that it’s important to “learn how to read as a writer,” but few can actually say how that skill is acquired. The program at Warren Wilson is really designed to do just that. It teaches a writer to be better reader—to look at a piece of writing, see how its particular effects are achieved, and understand how those specific strategies can be applied to one’s own writing.

LR: As the winner of the 2011 Kundiman Book Prize, can you tell us how has being a Kundiman fellow influenced you as a writer? Was it different from your MFA experience, and if so, how?

MO: Kundiman has both nurtured and supported my writing in a number of ways: retreats, residencies, and practical advice about moving through the writing world. But what I value most are the friendships and the deep sense of community that it has allowed me to experience.

While there are some similarities between what I experienced in an MFA Program and at Kundiman (lasting friendships, a sense of camaraderie with other writers), in general, it’s impractical to compare the two experiences. You apply to these different things for different reasons, and should approach each with separate expectations. Initially, I applied to Kundiman at a point when I was wrestling with issues of mixed-race Asian American identity, both in my personal life and in my writing. I went to the retreat to listen to and participate in a very specific type of conversation related to identity, community, and the arts. No one goes to an MFA program for those reasons. You go to an MFA program to be a student of poetry, to apprentice yourself to your art, to learn particular skills that—you hope—you’ll be able to use in a concrete way.

LR: Can you tell us what you’re working on now?

MO: I’m writing new poems and some very short stories. I’ve got a group of poems that I think could be the core of a new poetry manuscript, and I’m trying to understand how these poems are related.

6 thoughts on “A Conversation with Matthew Olzmann”