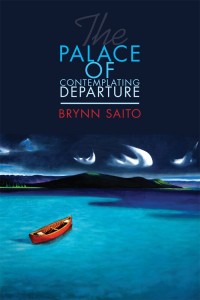

Brynn Saito is the author of The Palace of Contemplating Departure, winner of the Benjamin Saltman Poetry Award from Red Hen Press (2013). She also co-authored, with Traci Brimhall, Bright Power, Dark Peace, a chapbook of poetry from Diode Editions (2013). Brynn’s work has been anthologized by Helen Vendler and Ishmael Reed; it has also appeared in Virginia Quarterly Review, Ninth Letter, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and Pleiades. Brynn was born in the Central Valley of California to a Korean American mother and a Japanese American father. She is the recipient of a Kundiman Asian American Poetry Fellowship, the Poets 11 award from the San Francisco Public Library, and the Key West Literary Seminar’s Scotti Merrill Memorial Award. Currently, Brynn lives, writes, and teaches in the SF Bay Area.

* * *

LR: Travel, motion, and of course arriving and departing are recurring themes—the scaffolding of the book, even—in The Palace of Contemplating Departure. What was the process by which they became so significant for your collection?

BS: Basho says: “I myself have been tempted for a long time by the cloud-moving wind–filled with a strong desire to wander,” a sentiment that resonates with me. Almost more than the journey itself, I love dreaming of the journey–imagining the wonder and existing in the space(s) of desire. Some of that desire fuels the work in the book. Other poems were born out of actual journeys and travels–moves from east to west and back again, departures spurred by broken loves; stories of forced relocations. I wrote most of the book during the [previous] decade of my life, a decade in which I was saying goodbye a lot–to friends, cities, lovers, and myriad versions of myself.

LR: When reading and especially listening to you read from your book, one can hear some strong liturgical cadences, as in “Trembling on the Brink of a Mesquite Tree.” Can you talk a bit about what influenced these prayer-like sounds in your work?

BS: Ah, great insight! I’m only now realizing the extent to which poetry, for me, is prayer–a way of speaking to the unknown and collecting the echoes spoken in return. I don’t consider myself a religious person, but I have a strong interest in religious cultures, most likely rooted in my upbringing in both the Buddhist temple and the Christian church. The “Word” was everywhere, in childhood: chanted during Buddhist death rituals, spoken by the pastor on Sunday mornings. I read the Bible and internalized the cadences: in the Bible, as in many texts created and passed along with recitation and song, the word “and” strings together the many passages, creating a fluid and unstoppable delivery. My poetry is influenced by these traditions, and strives for a sort of spoken quality: I pay attention to how the poem sounds–its rhythms and pacings–much like something sung or chanted.

LR: The Palace of Contemplating Departure is divided into four sections: “Ruined Cities,” “Women and Children,” “Shape of Fire,” and “Steel and Light.” Can you tell us a bit about what each section represents and what led you to this narrative structure?

BS: Organizing the poems was one of the hardest tasks. Two moments come to mind as pivotal in formulating the structure of book: first, sitting in a cabin in the Michigan woods with my dear friend and poet, Traci Brimhall, a bottle of wine, and the pages of the manuscript splayed out before us on the floor. It was so helpful to have an outside eye look at what seemed to be a mess of incoherent voices. The second moment that comes to mind is me in my home in San Francisco taping the pages of manuscript to the various walls in my bedroom, so I could see how it was all literally hanging together.

After much guesswork, the form emerged: four parts–two short sections comprised of persona poems (“Women and Children” and “Steel and Light”) and two longer sections comprised of dramatic narrative poems rooted in lived experiences (“Ruined Cities” and “Shape of Fire”). Once the structure emerged, it seemed fated, in some strange way, thought it took years to find itself.

LR: Do you find that your post-MFA writing differs from your pre- and mid-MFA writing, and if so, how?

BS: I’d like to think I’m becoming better at this poetry thing as I get older, but who knows. I’m trying to try less, if that makes any sense–I want the work to be more playful, and less conscious, at the outset, of what it is “about.” More improvisational and surprising. I think the earlier poems were more content-driven: I wanted to write about something and would try hard to do so. Now, I let the writing reveal the subjects; I follow the voices that emerge with curiosity. I hope that makes for fresher, livelier work.

LR: During your MFA at Sarah Lawrence College, you met Traci Brimhall, with whom you co-wrote the chapbook Bright Power, Dark Peace. Can you talk a bit about your collaborative process with Traci? What did you learn about your own writing from the experience? Have you applied any of those techniques or lessons to subsequent work?

BS: Traci and I live in separate states (Michigan and California), so we co-wrote the chapbook using a shared Google document, each of us taking turns writing one stanza at a time until the poem was complete. Waiting for a stanza to appear is a little like waiting for the voice of the poem to emerge so you can follow the voice into the poem’s core energies and desires. It’s daunting, surprising, and a great exercise in letting go, in getting out of the way of yourself and your intentions for the poem. This was the greatest lesson of writing collaboratively: surrendering to the creative act, and seeing what emerges. I now consider all of my poems to be co-written, to some degree: it’s not just me and my intentions for the work in the creative space. There are other voices, other directions the poem might grow in, if I’m daring enough to give in to the moment.

LR: How do you balance your teaching life with your writing life? Does one feed into the other, and if so, how?

BS: As I see it, a classroom is a community–it’s a potentially imaginative, challenging, wild, and inspiring space in which all of us learn new things about each other and the world in which we live. Approaching a learning community with that mindset sustains my own artistic practice: I’m inspired by my students and the ways in which we converse and connect. On the other hand, I’m not sure if “balanced” can describe my writing/teaching (or art/work) life, at the moment! Like many in the arts, I’m in the position of holding a number of jobs, at any one moment, none of which are usually guaranteed past six months or so. There’s a kind of dynamism in the flux, which I’m grateful for–a flexibility allowing for travel and motion. There’s also a kind of low-grade anxiety which can hinder the writing process. I love teaching for the designated spaces of inquiry and transformation. I wonder, now, how to create more spaces like this in my life, in ways that are sustainable.

LR: As a member of an Asian American family that has been American for multiple generations, how do representations of your family’s experience come into play in your work, and what poetic strategies do you employ to handle them?

BS: This is one of the most alive questions for me, at the moment. I wonder how to write about past histories, those legacies of oppression and freedom that live in the present moment, using the tools of poetry. In The Palace of Contemplating Departure, I use persona poetry to tap into the voices of my grandparents’ generation; I hope to do more of this in the new work. There are blankets of silence, gaps in the narratives of my family’s past; there are fruitful tensions and polarities (Japan and Korea, East and West, the occupied cities and the dusty farmlands of my family’s arrival); there are ghosts. I am free–in a way that my grandmother wasn’t free, and my great-grandmother wasn’t free–to take up the pen and write write write into the silences. I aim to pursue that freedom to its end.

LR: You have spoken about the importance of community among poets. What do you think might be some practical measures that poets can take to foster community, especially post-MFA?

BS: I suppose a community is a little like a garden: it requires some tending to, in order to grow–a consistency of attention, accountability, investment. Sometimes, during certain “seasons” of my life I do this well; at other times, I don’t. Last August, for instance, Kundiman poets Dan Lau, Debbie Yee, Mia Malhotra and I formed a virtual writing community, in which we wrote a poem a night and emailed it to one another. It was such a fun and, ultimately, fruitful exercise. The new work that emerged there has formed the basis of my second book. I’d say to post-MFA poets: be diligent about forming online or face-to-face collectives with folks who will forever bother you with the questions: Are you writing? Why not? Want to write together?

Both my experience in the Kundiman fellowship and my friendship with Traci Brimhall have taught me that being a good literary citizen is about cultivating authentic connections and caring about one another. It’s about believing in and championing one another’s work. It’s a model that goes against the individualism so prevalent in a competitive, capitalistic North American social framework. Like many others, I wish I had more concentrated time for such invigorating and care-full spaces. But, as the poet Judy Grahn recently reminded me: little by little. Suddenly, you’ll look up from those stolen moments of writing and realize you’ve written another book.

LR: What projects are you working on now?

BS: I’ve become fascinated with the figure of the spiritual warrior–fighting monks, brave women, fierceness in times of brokenness. What are the myths that sustain such strength, such inner resiliency? What does it mean to fight for what you love? I see myself doing some reading, researching, journaling, and traveling, in order to trace this new inquiry. We’ll see what emerges when I “leave and leave into the questing” (as Linda Gregg puts it). More departures, more journeys. But this time, a focus on arrival: arriving to myself, arriving more fully to the things that I love.