This winter we had the privilege of speaking with poet Brian Komei Dempster about his new collection Seize, published last fall by Four Way Books. Dempster is a professor of rhetoric and language at the University of San Francisco, author of Topaz (Four Way Books, 2013), and editor of the award-winning From Our Side of the Fence: Growing Up in America’s Concentration Camps (Kearny Street Workshop, 2001) and Making Home from War: Stories of Japanese American Exile and Resettlement (Heyday, 2011). In this interview, we discuss the historical and ethical stakes of Dempster’s artmaking, his creative lineage as a mixed-race Japanese American, and, of course, the luminous figure of his son Brendan, whose epileptic seizures and resilience act as both inspiration and occasion for this remarkable new book.

* * *

LANTERN REVIEW: First off, congratulations on your just-released book Seize (Four Way Books, 2020)! Your poem “Night Sky” is such a beautiful opening, and the poem that came to mind as I was reading it (this, to be certain, says more about our friendship and ongoing conversation as fellow Japanese American poets than anything else!) was Lawson Fusao Inada’s “Concentration Constellation,” with its imagery of stars, jagged lines, and the flag/nation. Even if they exist only in my own mind, I sensed Inada’s words about the “jagged scar . . . the rusted wire / of a twisted and remembered fence” moving in the backdrop of the poem.

I hope this isn’t imposing unfairly on your work, but my sense is that you’re asking readers to understand the relatedness of these things: your son’s life and his epilepsy alongside your mother’s experience as an incarceration camp survivor, as well as other histories of seizure and brutality. Now that the book is written, these relationships feel obvious, vital; but I can imagine a time in which this was not yet the case, when you were perhaps moving blindly through your reactions to your son’s diagnosis and needs without a sense of how they might be connected to these more historical or political realities. How did you find your way into this book’s articulation?

BRIAN KOMEI DEMPSTER: I love that connection to Inada’s poem and that resonance, which I had not thought of before. Stars are such a mythic, long-standing image and symbol in poetry, and I can’t help but see our ancestors behind “the rusted wire” of this “twisted and remembered fence,” looking up at the night sky, imagining a ladder towards the stars, climbing rungs into the sky’s vast freedom.

Just as the suddenness of Executive Order 9066 and swift, forced removal from their homes must have been shocking for our families, so, too, was my son’s diagnosis a shock to our systems. Our lives upturned in an instant. Our expectations subverted. Like my mother and her family, my wife, Grace, and I had little time to think. Like them, we needed to act fast. At first, the reactions, as you point out, were involuntary, a river’s current shuttling us swiftly downstream as we paddled frantically for unseen shores. The poems, too, spilled out, some bursting blue sparks of rage, some bathed in a sad orange glow, flickering with guilt. Raw emotion superseded poetic craft or intention or anything else for that matter.

Only with the passing of time, as I stepped back from the immediacy of that initial shock, could I see the poems clearly. What was initially therapeutic venting onto the page—which I acknowledge was so important—became something different. As I moved from grief towards acceptance, these drafts began to speak to me as poems. When I cut away the rough edges, chiseled the black granite of words, I found jewels, arrived at a language that was beautiful in its realness as it sang our complicated truths. While I went through that process, it was helpful to remember the wise insight that Michael Collier—former director of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference—had shared with our group many years ago in his workshop. It went something like this: “A poem is smarter than we are. To realize a poem, we must listen to what it is trying to say to us.”

Following that cue, I saw that candid confessions and raw energy were powerful but, by themselves, not enough. I thought of my dual responsibility as an artist: to commit to the doing, which meant sitting down to do the hard work of writing and revising the work, and, at the same time, to inhabit the being, which was opening to and receiving the poems and their essence. This required a quieting of—and even playful dialogue with—the ego and its chattering voice, a letting go of perfectionistic tendencies, a tapping into energies that transformed the exhausted feeling of laboring through drafts into the excitement of creative discoveries, the pure fun of linguistic play and experimentation. Above all, I did my best to have an unwavering faith in process and hold firm to the belief that staying in such a space would keep me grounded, sane, and optimistic, and would lead to positive outcomes. I imagined myself in a house with many rooms, the poems crackling and alive, voices speaking to me through the walls. I cupped my ear to the walls, really listened to what the poems were trying to tell me. What images and details were they offering up, and how could I navigate and shape them? How could I effectively merge these specifics with the father-son story I was trying to tell? How could I get to the real truth of my son, which was something beyond language, when language was all I had, and my son communicated through touch and a primal language that alternated between euphonious and guttural sounds? How could I describe a boy who was both real and unreal, present and here, yet transcendent and otherworldly?

When I really opened my heart, it became a chamber my son could walk in or through, escape to or from. He became the boy that the poems were making him, and the work magically transformed. He became a bird, an angel, a lion, a sunflower, an oak. His journey morphed into a larger saga. The storms in his head became the storms my mom blinked at as a baby in Topaz. The seizures that gripped him became the hands of men who bound and chained others.

As I write this, these events still seize us, these linkages still sicken and sadden me. But they also show the power of my son. At the center of the storm, he takes us inside our collective vortex. As we swirl through histories and lives of trauma and pain, we search for love and bravery, forgiveness and calm. Here I quote Haruki Marukami: “And once the storm is over you won’t remember how you made it through, how you managed to survive.” Marukami’s words and my son remind us: because the storm gives us such an extreme and opposite reference point to normal life, the storm makes us feel and see everything more clearly. When we pass through the storm, we are changed. When the storm ends, we rest. The only way out is through.

LR: While many of the poems in Seize address experiences of brutality, at the book’s heart lies an unwavering commitment to care—though of course that commitment is not without its own journey through violence. This may be more of a question about self care, but how did you guard the space necessary to make these poems—to regard your son Brendan with such tranquility amidst the tumult, to speak with such lyric clarity into moments of pain, inherited and otherwise?

BKD: I am touched by your tender recognition of the emotional challenge I experienced writing this book. Your insight allows me to reflect on a larger question that is relevant to all of us as writers: How do we create safe spaces that allow us to dig deep into the psychic terrain of ourselves and, at the same time, remain in balance? The image that comes to mind is that of a garden. Our bodies, our minds, our art—all of it must be tended. In our lives, we plant seeds, we hope things will bloom. Along the way, we contend with periods of frost, drought, scavengers who threaten our crops; to make it through, we must believe in our harvest, its eventual fruition. What does this really mean as we navigate the real responsibilities and pressing demands of our own lives?

Guarding the space, as you nicely put it, means defining your relationship to your art. We are all different and need to figure out how to best weave writing into the fabric of our lives. When I was younger, I sometimes romanticized the notion that being a great poet meant giving oneself away to one’s art. As I grew older, however, I realized that being a writer needs to be integrated with being a good husband and dad. This model originates from what I witnessed in my family growing up: my mother painted and played the piano; my father played trombone and other instruments. They both worked full-time as educators. While my father, in particular, had to maintain a tricky balance between travel for music and commitment to family, we knew that he loved and cared for us. We, as children, were an integral part of our parents’ artistic and professional lives. Their passion for art did not threaten to extinguish us; nor did their goals diminish our importance on a daily basis.

To keep the space intact, we must create a system that allows us to protect our own time and energy. For us, this biggest factor is Brendan himself, who needs one-on-one care at all times. Caring for ourselves meant making sure Grace and I had enough help with him; when we did, I set aside hours on certain days where I attended only to the poems. When we didn’t, I tried to accept that the writing would have to wait. And with the demands of caring for him, Grace and I needed to be mindful of our relationship. Fortunately, because we are both writers, we understand the space and maintain a healthy reciprocity in terms of the amount of care we each do for him and also in terms of supporting things—from writing time to retreats and conferences—that allow our work to flourish.

While guarding the space is a process largely within our control, keeping faith in our work—and a good outlook—involves focused intention and effort. When my thoughts darkened, and I despaired about my son, his future; when I felt exposed or worried by what I had revealed about myself or him in a poem—I practiced the Buddhist discipline of abstracting thoughts, stepping outside them and seeing them from afar. I meditated, even if just for five or ten minutes. When I swam laps, water cleansed away toxic ruminations, reinvigorated me. I tried my best to live in Keats’s unresolved state of negative capability, the mystery and uncertainty that Buddhism encourages you to lean into rather than resist.

During the writing of Seize, all of this, of course, was challenging, and I wasn’t always successful. There were stops and starts, times when I thought a poem or the book wouldn’t come together and when we were exhausted from trying to care for our son while working full time and being called into the duties of our many roles. On certain long days of caregiving, it took effort to stay engaged and not become dulled by the monotony of feeding, dressing, and bathing my son. Yet when I entered his wavelength, I found joy in his clicks and coos for favorite foods; his shrieking laughter when I turned on the shower and he slammed the silver hose against the wall.

Edward Hirsch once talked about this idea to us in a poetry workshop, something to the effect that “Life doesn’t make room for poetry. You need to carve out that space on your own.” With a blend of imagination and pragmatism, we can find our own ways to build a fortress that fends off the intrusive, encroaching forces that oppose our artmaking. Here, I return to the garden. In the rich soil of our complicated lives, we turn up earth, pull out weeds, plant things, remain patient as they grow. It’s vital to care for our work as we do ourselves, to tend to it as we do our loved ones. If we can do that—and, in turn, defy the stereotype that writers must drink themselves to death or go crazy making their art—then we can reinforce the emergent model of the twenty first–century artist: one who harmonizes their life and creates in a sustainable way.

LR: Along with my previous question about care, I wanted to ask about the role of masculinity in your work, which you discussed in a recent interview with TriQuarterly. I felt it was no accident that some of the most frightening moments in your book are tied to performances of toxic masculinity—I’m thinking here of poor Jake Brown, of the terrifying Mr. Foster in “Jap,” also Derek’s father in “Target Practice,” and I wanted to hear more about the ways in which you feel Seize interrogates harmful notions of masculinity. What alternative modes of being does this book make possible?

BKD: As much as I wish toxic masculinity was not prevalent when I grew up and that it wasn’t still common today, I cannot deny reality. The characters you mentioned highlight this troubling issue. Using them to uncover toxic masculinity allowed me to dig deeper and perhaps get to the root of the problem. In this instance, braiding together the past and present revealed the unintended consequences of war and the damaging consequences of male aggression, intimidation, and violence. In writing these pieces, I think I myself came to some surprising conclusions about what it means to be a man in today’s world.

These poems own up to the harm that men do, the scary behaviors they enact. Mr. Foster totes his gun and shoots at imagined dangers while Derek’s father coaches the boys in such a way that turns baseball, a game that should be fun, into a cruel exercise. The poems, however, infer that these behaviors do not appear out of thin air. For both characters, war is an experience embedded so deep within their psyches that they now perceive life through its lens: you must be tough or sometimes kill to survive. As a poet, I do not cast judgment on these disturbing actions but present them with dimensionality. That way, the audience can interpret who these characters are and speculate about the causes—along with war, who and what shaped them so they turned out this way? Why do these men and other men do what they do?

One possible answer is that these men do not engage in enough self reflection or—even if they do—do not fully realize or care about the damage their actions cause. They are, to a degree, living what some spiritual thinkers might call an unconscious life. That doesn’t excuse their behavior, but it at least explains it. In “A Boy,” the bullying of Jake Brown by the group of boys demonstrates the extent to which we, growing up, absorb these toxic beliefs and act accordingly. Jake is an outcast because he can’t play sports well and looks different. I witnessed this type of behavior time and again, and it was hardly ever questioned. But even as a kid, I sensed this intimidation or disparagement of others was wrong. As such, in the rare instances of being a participant, or in my more common experience of being an observer, I felt twinges of guilt that I suppressed.

This poem, to me, is an owning up to and apology for the wrongdoings boys do to other boys. It’s also a scary reminder that grown men can subconsciously fall into the trap of these beliefs even when they know they are wrong, as evidenced by some of the speaker-father’s actions towards his son in “A Boy.”

The speaker’s feelings of vulnerability and guilt in these poems—as well as the redemptive passages in “A Boy”—create the pathway towards the alternative modes of being that you ask about here. Throughout Seize, and especially in the final section, the father-speaker reveals the more tender, vulnerable sides of his voice and self. We see this in “Son Sutra,” where he speaks gently and achingly about his son in the rhythm of a lullaby; in “Da,” where he feels his son’s sound ripple like a pebble in his chest; and in “Robin,” where he recognizes his boy’s power as Brendan symbolically flies in his walker. Moreover, other characters like my trombonist father and cellist brother reveal their sensitivity through music, their brass and oak sounds healing forces for my son. Finally, the strong women figures bring a different energy and perspective. My grandmother carries my mother safely in Tanforan; my mother tells the story of Topaz to Brendan and honors his silence; Grace anchors our family together, providing honest insight and a steady radiance. By example and action, these female characters, along with stable male characters, both matured by hardship and by hard-won consciousness, show the balance of a significant poetic and real world.

LR: I didn’t realize until after I’d finished reading Seize that its cover features a painting by your mother, the artist Suiren. Her extraordinary presence throughout the poems—as a historical presence, a figure of hope; as a lyric voice, even, in “My Mother Watches Horses with Brendan”—makes this a truly intergenerational work. You’ve spoken elsewhere about the relationship between Seize and your mother’s cover art, but can you elaborate on the broader conversation across form and generation that takes place between your respective creative practices?

BKD: In a 2014 presentation for Topaz at the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle, my mother paired paintings with my poems, her art giving new depth and meaning to the words. As her striking visuals scrolled across the screen and I read the poems, my father improvised music on his trombone, didgeridoo, and garden hose. After that event, I recall telling her, “Your painting needs to be the cover for my next book.” A few years ago, as we looked through piece after piece, we finally came upon the one that would be the image for Seize. In this painting and others, I keep finding new resonances, grateful to be enriched by our conversation and how it informs my development as an artist.

The conversation between our art forms has sustained me for many years. In my first book, Topaz, several poems imagine her father—my grandfather, Ojichan—using brushstrokes to evoke his wife, miles away, and to paint himself a way beyond the prison camp fences. Ojichan, a master calligrapher, is a salient influence on my mother’s work, as seen by her echoes of his calligraphic style and gestures and by her occasional incorporation of his calligraphy into certain compositions. Although our mediums are different, the core issues intersect. In visual art and poems, we balance presence and absence, the concrete with the ineffable.

When I look at some of her paintings, colors and shapes elide, blurring space, time, and image, and I can’t help but think of the camp experience. There were the shards of the past from those relatives who were willing to speak and the larger silences in my mother’s family: a silence driven by their shame, their desire to move on, and their wish to protect us. Fragments are all my mother can remember. I have so many questions that she can’t quite answer because she was only an infant at the time. What really happened? What was it like for her to go through this at such a young age? To have her father torn from her? To not know where he was, when he would come back? “I sensed him missing,” she told me. In Seize, I wrote poems like “My Mother at One” and “My Mother in Tanforan” to reclaim what she had lost. I envisioned her days in a Tanforan horse stall, which was the repurposed barrack for her and her family; in a tar paper shack in Topaz, her father miles away from them. I described what she might have recalled if she had had the words and acknowledged the gaps. As Li-Young Lee does in the poem “Mnemonic” and others, I let the instability of memory inhabit the speaker, dramatized her nonlinear process of piecing the shards into some coherent form.

In my work, her artistry shows agency and a creative, nurturing energy. My mother, as you note, is the conduit between generations. While her character does not let the past consume her or make her bitter, her history is inseparable from how she sees the present. In “My Mother Watches Horses with Brendan,” we understand my son more fully through her voice. Together, they watch horses and both understand what it means to be confined: for him, in a wheelchair, at times unable to walk; for her, behind a fence, unable to leave. We feel her compassion and unconditional acceptance of Brendan and his nonverbal world, telling him one day she’ll paint him the story of Topaz, that love is inseparable from silence.

When we grew up, my mom supported my dad’s career so he could tour and record albums. As time passed, their roles shifted, and my mother was able to give more time to her art. One day, when my father had finished helping her hang the paintings for a studio showing, he said, “It’s like we have a little church here.” He meant several things by that: standing among her paintings felt like being in a room of stained glass windows, each with their own design and story. It was like entering the altar area of Ojichan’s temple, the Nichiren Buddhist church where she grew up, his calligraphy and other works of art adorning the walls and space. It’s my hope that Topaz and Seize have that effect: each poem a window with its own story, the windows together refracting our saga.

The interchange between our work is also underscored by the ways we create. “My process has changed from my days of art school,” she tells me. “Now I work from the inside out.” I can relate to that statement in the uncensored act of freewriting, when a new draft offers a surprising discovery. As she describes, “I am a vessel. Through me, the truth comes out.” In Seize, she calls Brendan “part of the source, a work of living art.” For her, painting is meditation, a transformative experience, the improvisational process connecting her to the abstract expressionists. She, like my father, engages in real-time composition. Sometimes she paints with headphones on, her brush following the flow of my father’s music or other pieces. Like her, I find inspiration in other forms—from her art to my father and brother’s recordings to movies and photos. As a college tennis player, I discovered how much better I played when I became less cerebral and more intuitive. Like her, I try to get in the zone and stay there.

LR: As much as I applaud the incredible vulnerability of your book, I also wonder how you navigated the ethical stakes of writing about some of your family’s most intimate struggles, especially when this includes the experiences of others: your son, your wife, your parents and brother. Did you encounter internal or external resistance in the drafting of the manuscript? What emboldened you to press on—to touch the rawest nerve, to gaze without turning away, and what was it like to bring these works, which originated as a way to process “chaotic feelings and thoughts,” as you say in your interview with Shenandoah, into a fully realized collection of poetry?

BKD: This is an important consideration for all writers who mold the raw, charged clay of autobiographical material. While I hope readers will see my family members as characters and not assume that everything in a poem is based on real life, I know this is beyond my control. As writers, we walk a tightrope, pulled on by our creative urges but aware of our conscience.

This tension—between producing art and ethical representation—is one that I could only resolve through conversations with those impacted. One of my biggest concerns was the poems “Dissonance” and “Bandage,” which described the assault of my brother, Loren, by a group of his fellow middle school students, an event that had not only damaged him physically but left him with psychological scars. I could not shake this incident; as his older brother, I felt angry, guilty, and sad that I was unable to protect him. Over the years, Loren reassured me it was fine for me to write about this, but as publication neared, my worries intensified. I feared that his reading of the poems in published form, combined with his knowledge that his story was now out in the world, could reenact his original trauma.

His response was not only gracious but also made me tearful: “Brian, I want you to go ahead and publish these. They give voice to issues I’m still struggling to articulate, trying to resolve.” Shortly after, he wrote to me that “Bandage” reached him “on a personal connection kind of level. It speaks my experience in a way I could never put into words, so thank you, truly.”

I didn’t anticipate that these poems would be a catalyst for Loren, who is a musician, to open up. His songs “See People Like Me” and “They’re All Coming”—likely to be included in his next album—are his own artistic processing of these life-altering events. At a recent Facebook Live performance, he noted my influence on getting him to voice his truth, which deeply moved me. The moment reminded me: although exploring trauma through art is a difficult, complex process, it can bring us closer.

I had less anxiety concerning my parents because we had already discussed such issues when I published Topaz. Like my brother, they are artists who understand the necessity of pushing ourselves and taking risks with our art and are also in tune with the complicated nature of source materials. They understood that I drew from our own lives yet also infused my poems with imagined details, exercised creative license. As such, they were open and supportive. But I was still mindful of their representation and did my best to make their characters well rounded. While I show the challenges they face—tensions due to long trips my dad takes as a touring musician and familial disapproval of their interracial marriage—I balance that with their positive attributes and abiding love. As I’ve discussed, my mother’s character is multilayered; I wanted my father to have that same depth. His protective side emerges in poems like “Jap,” where he stands up to Mr. F’s racism; in “Exhaust,” he is sure to not leave on a trip until he gives my mother a goodbye kiss. “Blue Creation” shows the caring efforts he makes when he is far away, sending postcards and gifts home to us.

Fortunately, my wife, Grace, is also a writer and obviously understands the artistic process. She imagines historical worlds of romance while I build the world that I imagine my son lives in—all he has gone through and all we have gone through with him. Although our subject matter differs, we both create art that brings us meaning and joy and even heals us.

In Seize, it was vital to depict the strain on our marriage from having a special-needs son. “The Door,” “Stunted Crop,” and “Broken” show the way that, in a charged situation, when my wife and I are both fatigued, tension and frustration are inevitable. At the same time, pieces like “Robin” and “Brendan’s I Am” give a deeper look into our physical and spiritual connection, our strength and optimism.

Although Brendan can’t directly tell us what he feels or thinks, I am responsible as a parent and as a poet to keep discovering who he is. This requires reflecting on the reactions and signs he gives us daily and piecing together the silences with patience. We are all searching together for meaning and purpose. At times I worry that I may not be portraying him fully or expressing his life in all of its nuances. But I’d like to think he appreciates that I’m at least trying. For both me and Grace, it is important for us not only to keep writing but also to do so with a certain mindset.

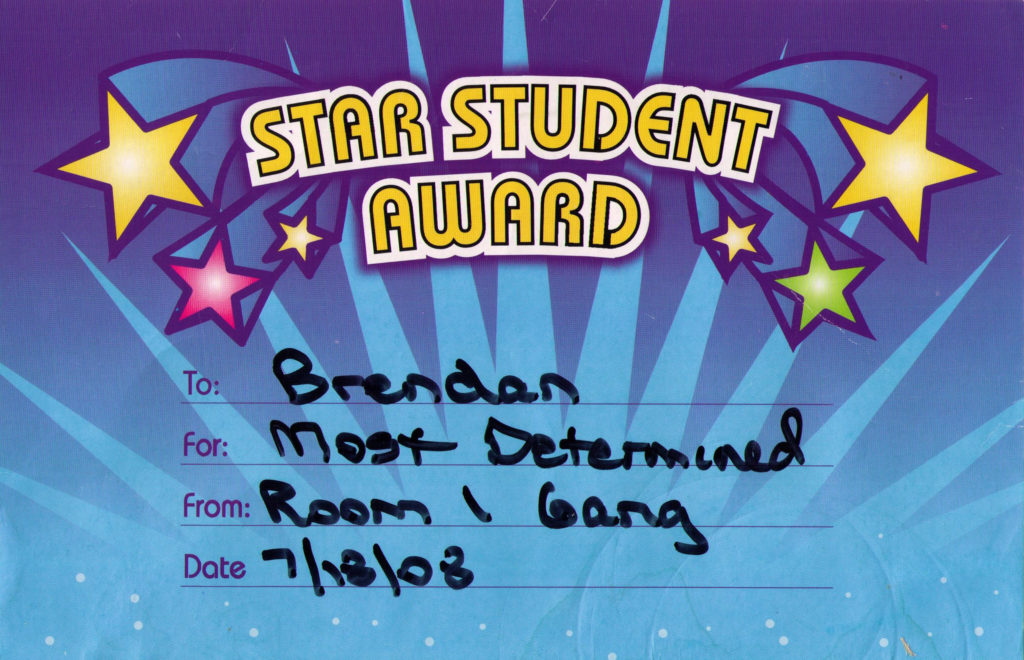

Our son leads by example: he stays positive under duress, even while racked with debilitating seizures; if he can do that, then it is incumbent upon us to find equilibrium as parents and artists. It would seem petty to complain about our lot in life or to be neurotic about our writing. I remember Brendan winning an award in preschool. I still have the certificate. On the sheet of sturdy blue paper, it says “Most Determined.”

LR: At least to my mind, one of the most important contributions of Seize is its intersectionality. Even as much of its subject matter and formal concerns locate it in what I sense is a growing body of writing by Japanese American authors, I’m curious to hear how you feel your book complicates or challenges this existing work—its assumptions, subject(s), aesthetics. From a slightly different angle, how does the book expand the conversation about caring for children with epilepsy, or even parenthood more generally?

BKD: My hope is that Seize challenges assumptions about who Japanese Americans are and what we can write about. As a younger poet, I found reading David Mura’s poems had this effect. Mura confronted difficult and taboo subjects. Jump cutting between narratives, he intertwined race, gender, and sexuality, helping me see new, intersectional possibilities for my work. Garrett Hongo’s poetry spoke to me, too. From the dramatic monologue of a gardener playing his shakuhachi after the war to the elegy with a speaker looking out from a pier, reflecting on the landscape and loss of his father, his poems combined an epic, sweeping quality with a tender, lyric sensibility.

While writers like Hongo, Mura, Lawson Fusao Inada, Janice Mirikitani, and others opened doors for us, got us to think bigger about what our work could do, we are also indebted to our shared literary predecessors—those important voices like Hisaye Yamamoto and Wakako Yamauchi who set the foundation for all of us long ago. We continue to write from this tradition and lineage. Yet we all move the genre forward by adding our own versions of identity making and intersectionality into the mix. And because many of us alive today did not directly experience the camps, this past seems like a ghost we keep chasing, morphing into various forms. In our poems and stories, we conjure ancestral voices behind barbed wire, explore the silence of past generations, revealing the imprints of trauma. It seems that we are all writing at our own crossroads, tilting on the axis between then and now, bridging who we are and who we are becoming through the multiple dimensions of our experience. I see this happening in your [Mia’s] debut book, Isako Isako, where you elegantly weave an “I” speaker with the mythical character of Isako; in Julie Otsuka’s novel, The Buddha in the Attic, where the “we” voice reveals the power of a collective consciousness. Your work, like novelist Ruth Ozeki’s and poet Brynn Saito’s, creates worlds where gender, history, culture, and spirituality overlap. While poet W. Todd Kaneko juxtaposes father-son relationships and pro wrestling, Brandon Shimoda explores the bombing and aftereffects of Hiroshima. A common thread that runs through our work and those who came before us, the incarceration is a wound that we must acknowledge and process.

I hope that Seize enriches the genre of Japanese American writing in a meaningful way. While the father-son quest is a universal trope that has been rewritten many times, my particular story introduces distinct themes. By juxtaposing forms of physical and psychological seizure, the poems reveal previously unseen connections. They create a new lexicon for my boy, Brendan: his unique methods of communication and how he reshapes our views. My book is just one of many that brings issues of disability closer to the center. By expanding what it is possible to write about, we can spur on others to confront this challenging subject.

In adding my own take, Seize expands the ever-widening conversation about epilepsy and parenting. I join Asian Pacific American poets like Oliver de la Paz and Brenda Shaughnessy, whose moving, nuanced portraits of their own children remind me that I am not alone. Likewise, it would make me happy to know that my poems are a touchstone for other parents who struggle with similar challenges. That it would help them say what is hard to admit. Sometimes when people find out about Brendan, they say, “I’m so sorry.” Even though the intention behind that statement is a good one, I feel uncomfortable hearing this because it seems that I, that we, are being pitied. “Brendan is a gift,” I reply. “The best thing that has ever happened to us.” It’s true. Children like Brendan—and in fact, all children—teach us. Make us dig deep for solutions. Shape us into more rounded human beings, helping us see that suffering and joy can be held simultaneously. At the same time, parenting and caregiving can leave us exhausted and at war with ourselves. My book acknowledges all of that yet offers clear paths forward: from sorrow towards love, from crisis towards peace, from shame towards acceptance.

LR: In “Give and Take,” you speak of how your son “glows inside // with ancient women / burning,” calling him a “cathedral, radiant.” In moments like these, Brendan’s presence is profoundly visionary. Other times, you speak of him with a hushed tenderness: Brendan as fragile bird, as heavy-headed sunflower. I’ve thought a lot about this in my own life as a poet and parent, but what do you feel is the relationship between the representational and the real, especially when it comes to your own child? Through poetry, who has Brendan become to you, and how does this inform the day-to-day reality of being his parent?

BKD: The daily reality of being Brendan’s dad and a poet means I must attend to him and all the details and their meaning. When he does disco spin moves in the kitchen after he takes a bite of prime rib, I’m reminded of when he couldn’t walk, and we had to push him everywhere in his roadster wheelchair. When he grins, Grace and I see his missing front teeth and think of all the times he’s fallen down, hurt himself. All the times he’s gotten back up. After he’s finished eating, he taps my hand, which means he wants to go to our master bedroom, which Grace and I have renamed his clubhouse, to sit atop our bed and stare out the window. Sometimes he’s quiet and just looks out at the stars. Other times he laughs at some thought or joke I wish I could be a part of. I peek in at him, wonder what he’s thinking. What I love the most: those times when he taps my right hand “yes,” he wants me to stay; he likes it when I walk down the bedroom hallway and take a shower so he can listen to the sound of running water. These days he lets me stand even closer to him, at the foot of the bed where I lay out the laundry, fold our clothes.

Imagining who Brendan is through my words is paradoxical. The more I describe my son, the more I realize he is not quite describable. Even as I attempt to craft who he is, encompassing his full nature can feel elusive. Yet these poems allow me to better see him. Through writing, I discover him, capture important and hidden aspects of his being. His life is our center point and radiates outward, like waves of sound from the temple bell in my grandfather’s church.

* * *

Brian Komei Dempster‘s second poetry collection, Seize, was published by Four Way Books in fall 2020. His debut book of poems, Topaz (Four Way Books, 2013), received the 15 Bytes 2014 Book Award in Poetry. Dempster is editor of From Our Side of the Fence: Growing Up in America’s Concentration Camps (Kearny Street Workshop, 2001), which received a 2007 Nisei Voices Award from the National Japanese American Historical Society, and Making Home from War: Stories of Japanese American Exile and Resettlement (Heyday, 2011). He is a professor of rhetoric and language at the University of San Francisco, where he serves as director of administration for the master of arts in Asia Pacific studies program.

ALSO RECOMMENDED:

Nate Marshall, Finna (One World, 2020)

Please consider supporting an indie bookstore with your purchase.

As an Asian American–focused publication, Lantern Review stands for diversity within the literary world. In solidarity with other communities of color and in an effort to connect our readers with a wider range of voices, we recommend a different collection by a non-Asian-American-identified BIPOC poet in each blog post.