To our beloved community:

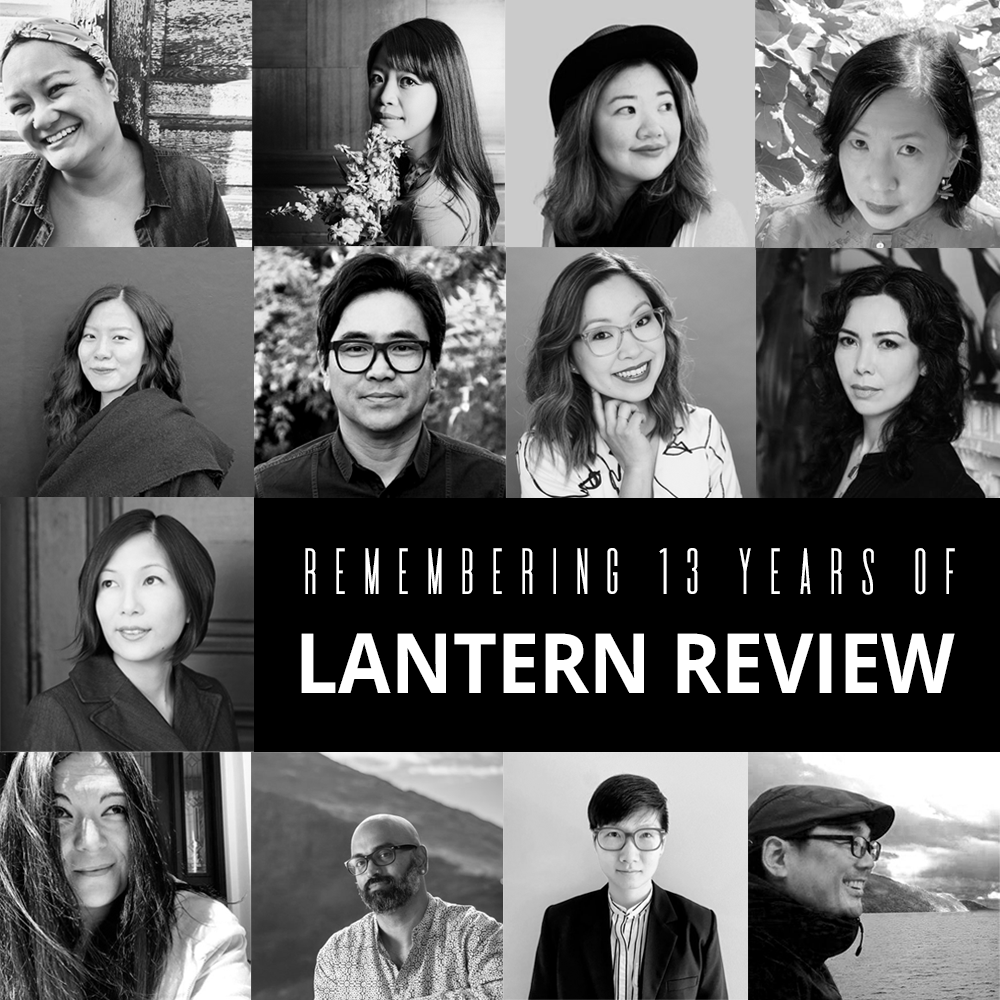

Today marks the end of the adventure that has been Lantern Review. Getting to work on the magazine, the blog, our newsletter—all of it has been a shelter and a balm for us. It’s helped to sustain us as editors, as literary professionals, as poets, as teachers, as friends. And as we look back at the work of the last thirteen years, it’s hard not to be proud.

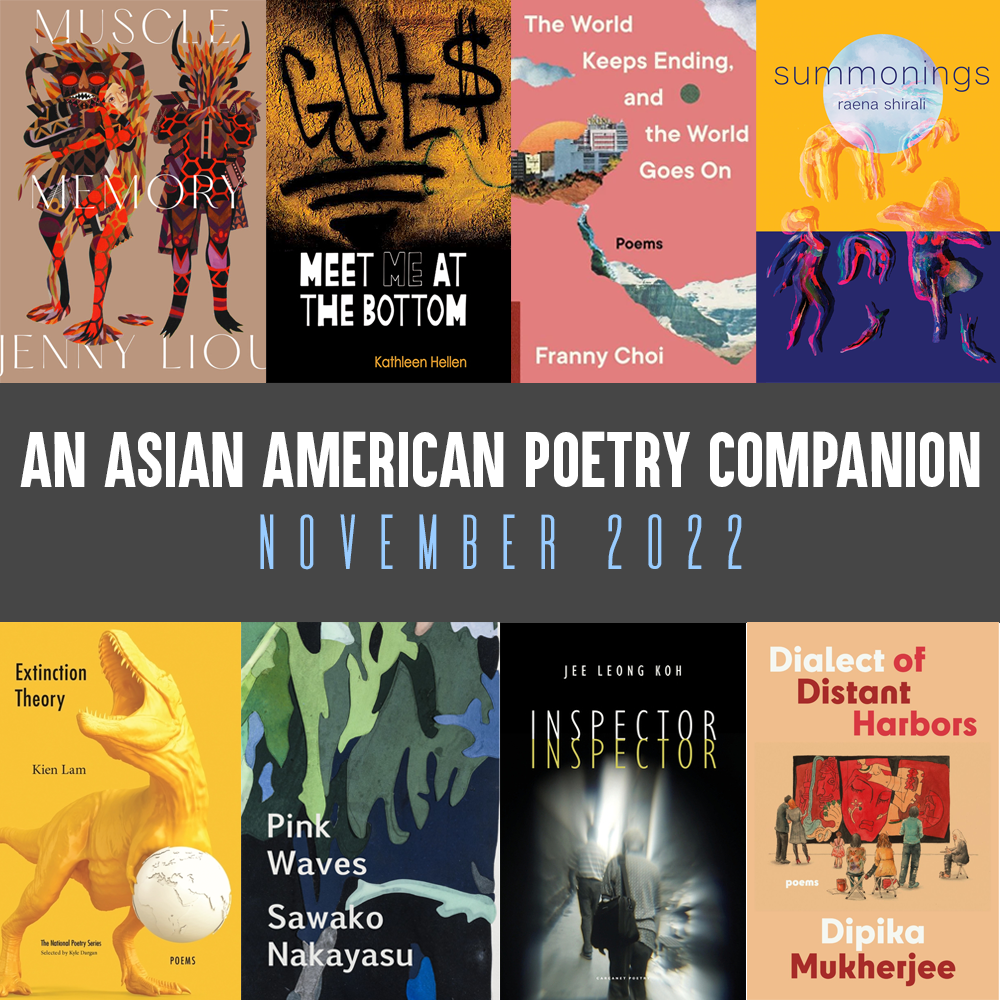

Over the course of our tenure, we’ve produced fifteen issues of the magazine and posted hundreds of interviews, reviews, roundups, and more on our blog. We’ve been honored to publish bedrock figures from the Asian American poetry community, among them Amy Uyematsu, Oliver de la Paz, Jon Pineda, Barbara Jane Reyes, Eileen R. Tabios, Bryan Thao Worra, and several state poets laureate, including Luisa A. Igloria (VA), Lee Herrick (CA), and JoAnn Balingit (DE).

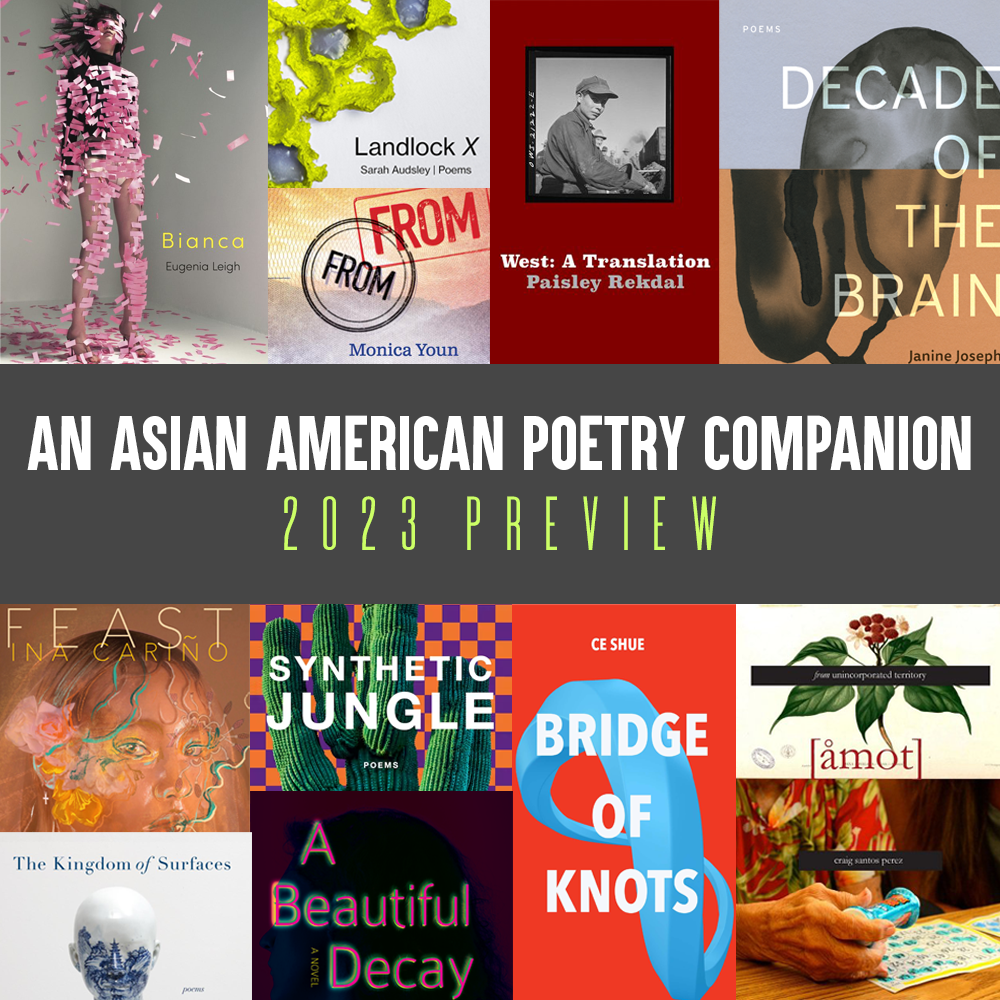

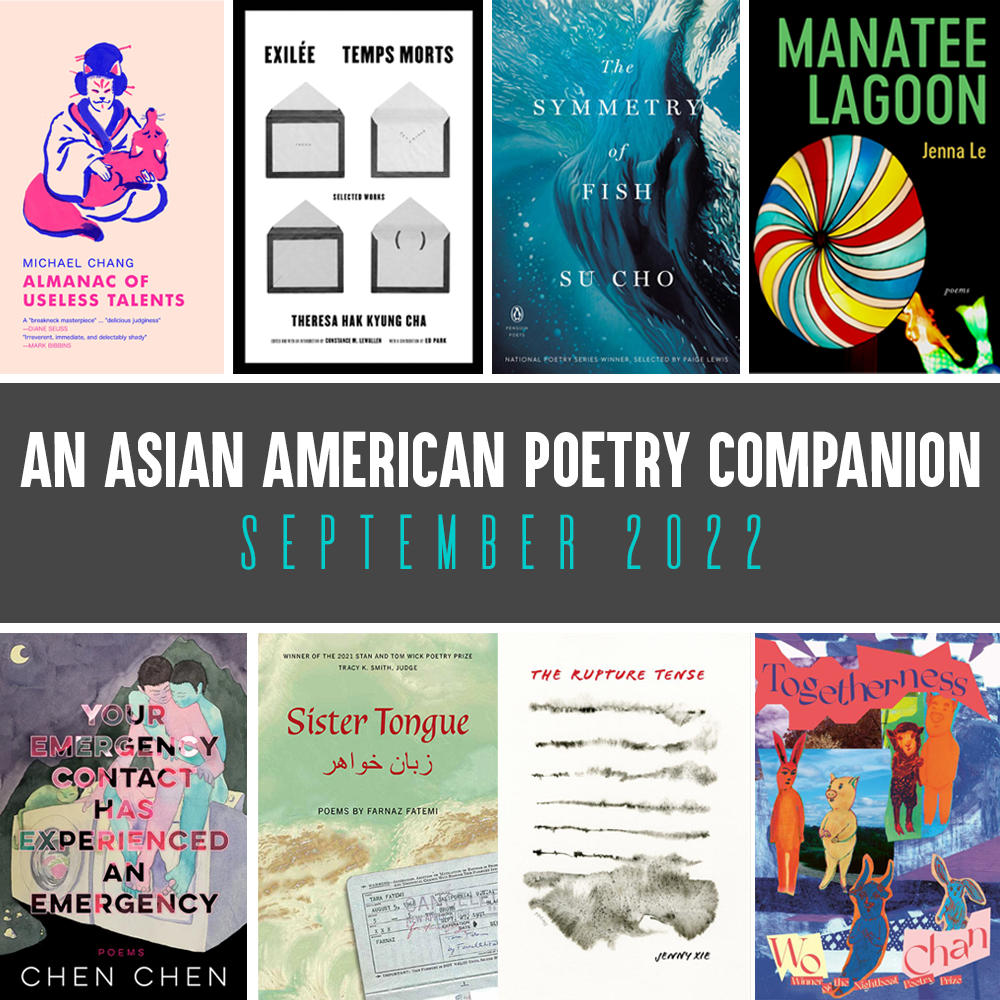

And we’ve had the privilege of cheering along as some of our earliest contributors’ stars have risen—Ocean Vuong has gone on to win the TS Eliot Prize and the MacArthur; Mai Der Vang’s books have won multiple accolades, including an American Book Award and the Academy of American Poets’ Lenore Marshall and First Book Awards. Eugenia Leigh, Rajiv Mohabir, Michelle Peñaloza, Matthew Olzmann, Brynn Saito, Kenji C. Liu, Khaty Xiong, Janine Joseph, Neil Aitken, Sally Wen Mao, Jane Wong, Tarfia Faizullah, W. Todd Kaneko, and so many more have published critically acclaimed first, second, even third collections during LR’s lifespan. We were the first to publish Monica Ong’s visual poetry before her book Silent Anatomies came out. Shelley Wong, whom we first published in Issue 6, went on to be longlisted for the National Book Award this year (for her book As She Appears). We interviewed Chen Chen about his first two chapbooks before his full-length collections came bursting onto the scene with such success—to this day, we meet young, aspiring poets who tell us that his books have changed their lives.

There have been challenges, of course, and we’ve had to grow—adapting everything from our editorial processes to our magazine’s visual layout. But we’ve shifted and pivoted and scrapped and survived. And we’ve learned so much from all of you along the way. From the persistence that compelled you to keep asking when the magazine would come back during its 2015–2019 publication gap. From the grace and generosity that’s led so many of you to check in with us—What do you need? How can I help? How can we carry your load with you?—when you’ve seen us struggling. From your willingness to (kindly but forthrightly!) keep us accountable for our mistakes. From your openness to our experiments in form, format, and aesthetic. From your unfailing enthusiasm each time we’ve shared something new: “poetry tastings” and stickers at festivals, an installation at a museum, themed issues, a youth folio, poems that did unusual things (scrolled, zoomed, talked).

From you, we’ve learned how resilient the Asian American poetry community is. That it’s deeper and more far-reaching than we could ever have imagined as young MFA students embarking on a mission to find role models and peers. We’re encouraged by the next generation of emerging Asian American poets and what we’re watching them do right now. And we hope that, for every young student out there who feels as isolated as we once did—that the work we’ve done will serve as a testament to the fact that they are not alone, as well as inspiration to forge their own new paths.

Starting today, our website will shift from being an active publication to an archive and resource. Our blog and magazine will continue to remain freely available online for as long as we’re able to support them (hopefully for many years yet), and we’ve forefronted our archives page to make finding a particular poet’s work or a specific issue easier.

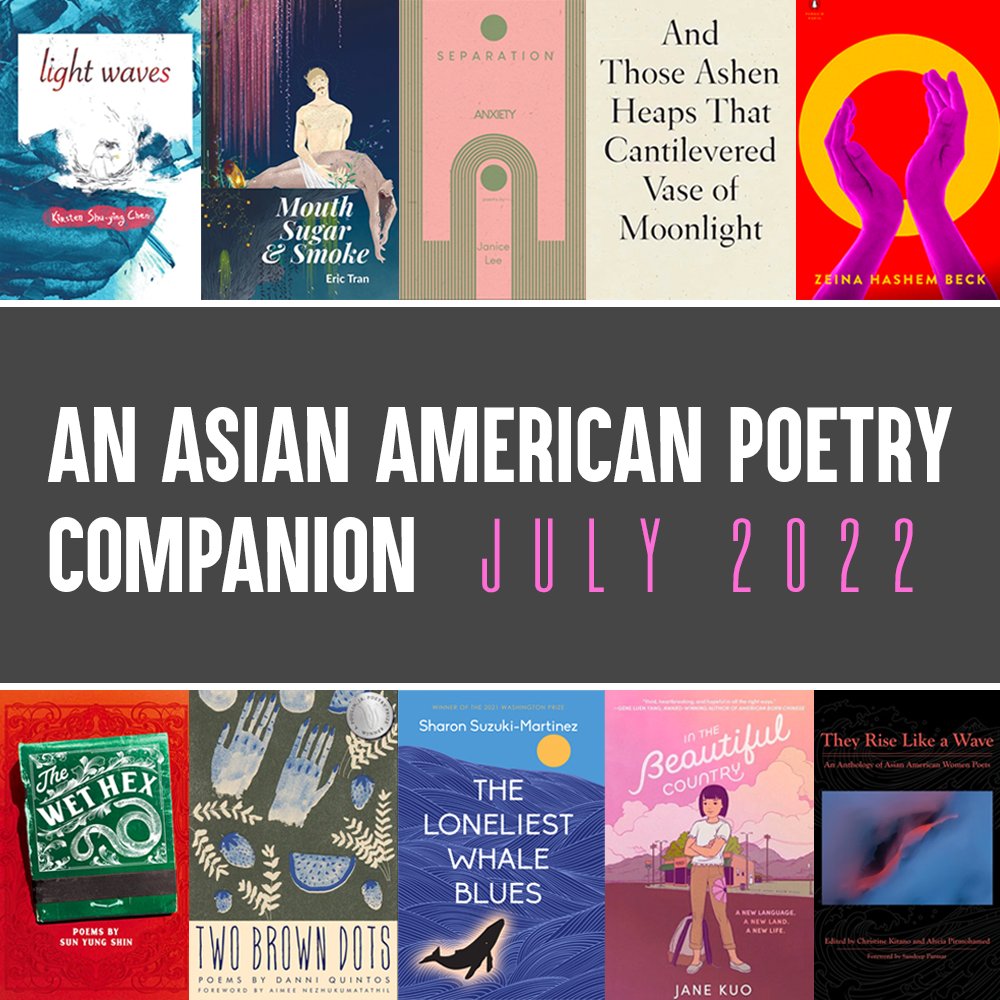

In 2009, we set out on a journey to “shed light” on Asian American poetry. And we think, for at least the span of LR’s decade-plus of existence, that we’ve accomplished that goal well. The Asian American poetry scene is thriving today in ways that we never could have envisioned. We are in a golden age where there are lots of us actively creating the work and getting published. Today, young Asian American writers have the privilege to grow up knowing and loving the work of older poets who look like them. Let that sink in: there are Asian American kids reading Franny Choi and Aimee Nezhukhumatathil and Ocean Vuong in high school. That’s something that we could never have dreamed of when we were teens. That’s how far visibility for our community has come.

We’re confident that the literary community is not just ready for more Asian American voices; we have already arrived, and we’ve no doubt that the road ahead will look very different, in the best way possible. And so, as we step back, we’re eager to see the next generation of Asian American poets and editors step forward to take up the torch. We hope you’ll support them and keep the flame burning. We hope you’ll be a part of our community’s future. Because we know that future will be bright.

Light and peace to you always.

With deepest gratitude,

Iris & Mia