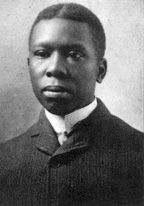

For the poet of color, whose repository of language is often composed of multiple “englishes” (standard English being only one of them), the dialect poem can become a site of great experimentation–and great conflict. Best known in the American canon, at least in terms of dialect poetry, are the works of noted African Americans poets like Paul Laurence Dunbar and later, Langston Hughes with his jazz and blues poetry during the Harlem Renaissance. Dunbar, often considered to be the first African American poet of national eminence, is widely read both for his black vernacular and standard English verse. The marked differences in syntax, register, tone, and even subject matter that distinguish works like “We Wear the Mask” or “Ships That Pass in the Night” from “When Malindy Sings” are fascinating to me, particularly because both “voices” are grounded, I think, in Dunbar’s understanding of himself as an English language/African American poet.

Equally fascinating to me are figures like Countee Cullen, who, like Hughes, was a prominent figure in the Harlem Renaissance, but who (unlike Hughes) vociferously rejected the use of black vernacular in his poetry. Why? Because he considered poetry worth reading to be poetry that was carefully metered, rhymed, and executed in the tradition of Keats and Shelley, his two greatest influences. For a more detailed exploration of Cullen and Hughes’ differing views on questions of racial representation, poetics, and aesthetics, see the comparative essay “Jazz or Junk?” posted on Renaissance Collage.

The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines the word “dialect” as “a regional variety of language distinguished by features of vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation… ” How this relates to my own practice is as follows. In examining the unique linguistic sensibility, grammatical constructions, and linguistic features of Japanese American english, at least the varieties of these dialects that run through my head whenever I invoke an “Issei voice” or “Nisei voice,” I have found some rich linguistic textures for my own writing. At this point in time, however, the manner in which I represent these voices on the page is something that, as I mentioned earlier, poses not only great experimental possibility, but also some terribly conflicted dilemmas.

My anxieties about writing “dialect” or “accent-inflected” poetry stem from the often vicious ways that “broken” English has been wielded against peoples of Asian descent as a tool for racist bigotry and xenophobia. Stories of my father growing up in inner-city Richmond to taunts of “Chinese, Japanese, dirty knees, money please!” and “Ching-chong Chinaman!” are so deeply embedded in my consciousness that when I sit down to represent an “Asian” voice on the page, I can’t help but be haunted by these echoes. It’s enough to drive the dialect out of any Chinaman’s (or Chinawoman’s) poetry. Perhaps there’s a little Countee Cullen in all of us.

All the same, the impulse to give voice and poetic texture to the englishes I hear in my family, in our ancestry beats strongly. Poets like Hughes, Dunbar, and even the more contemporary African American voices like Patricia Smith and Sonia Sanchez (to name a few) urge me to consider that it can be done, that a voice free of racist taunts can be constructed–fearlessly, and in the face of, as Frantz Fanon would said, “ten thousand racists.”

Below are some of my more recent attempts to reconstruct some of the voices that racism has (and still may) constructed as cheap parodies.

I am good American citizen. FBI,

They tell me, “You go to jail” and I go.

No fuss, just go.

Now

in barracks

That smell of horseshit, I wait.

This first excerpt is from a poem entitled “What the Issei Said,” and is partially constructed from the voices of my grandparents and their generation (the Nisei), and partially from the imagined voices of my great-grandparents (the Issei). Though I never met the great-grandfathers detained by the FBI during World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, I have grown up with a deep consciousness of their narrative presence in my family history. Their voice is a part of my inheritance, and there are times when my notions about this voice (some of which are, admittedly, entirely fictive) guide the manner in which I craft language.

At the same time, I feel a tremendous uneasiness when “representing” their voices in this way. Would they ever say “horseshit” to describe the barracks their families lived in during the internment era? Does dropping their articles undermine them as speakers in an english language poem? This excerpt is cobbled together from my perception of their behavior during the war and threads of family myth: the FBI appeared on our doorstep one day, that my great-grandfather simply picked up his hat, his umbrella, and his briefcase and allowed himself to be escorted out the door and into the car. At the same time, I imagine that much of this is imagined truth, gleaned from other (perhaps partially fictive) accounts of the incarceration of Japanese American community leaders immediately after Pearl Harbor. The umbrella, for instance. Was there actually an umbrella?

The redeeming feature of this cursory attempt at dialect poetry is, I feel, in the powerful syntax of Japanese-inflected english. “FBI / They tell me” is syntactical move that thrusts the subject to the forefront of the poem in a way that the more domesticized “The FBI tell me” does not. In this way, the unique grammatical constructions of this voice actually lend poetic impetus to the language. In other moments, like “I am good American citizen,” it is less clear how this variety of english is working in concert with poetic thought. The sentiment seems to fall flat, to simply echo an overly earnest and somewhat petulant Asian American voice that popular (and racist) media has represented one too many times.

This second excerpt is from a poem I have been developing from several different sources. The voice I ventriloquize in this instance is a mock-Orientalist parody of the Japanese geisha, one prevalent in western media dating back to the 1800’s. The film Memoirs of a Geisha, which gave rise to tremendous controversy when it was released in 2005, provided me with more contemporary material to work with, though the essential Orientalist bent of the film (Japanese female faces–and voices. And bodies–posed, directed, and constructed by western males) is old hat.

With such horror you will clap

Hand to open mouth when,

With delicate motion and flick of wrist,

Same as inviting gesture I make

When pouring tea for patron,

I brush kimono sleeve back

To reveal hairy wrist. You

Perhaps do not find this so nice.

Only try to remember. Bara ni toge ari.

Every rose has its thorn.

And so, the journey continues. How to represent the complexity of Japanese American english, with all its troubled history and relationship to American english, America, and the West in general? How to negotiate the troubled (and sometimes imagined) waters between the “Orient” and the “West”? No answers for now, only more questions, but next on my reading list is David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly, which recasts Giacomo Puccini’s Orientalist 1904 opera Madame Butterfly in a radical new light. I also hope to take a look at Madame Chrysantheme, the 1887 novel by French Orientalist Pierre Loti that inspired Puccini’s opera in the first place.

I heard a poet/prof on the radio today, who’d been to Obama’s White House for some shindig (I wonder what the origin of that word is), talking that poetry had to get closer to the language of speech or it was done for. I enjoyed your article and experiments as I check the web for material on dialect verse.