Panax Ginseng is a monthly column by Henry W. Leung exploring the transgressions of linguistic and geographic borders in Asian American literature, especially those which result in hybrid genres, forms, vernaculars, and visions. The column title suggests the congenital borrowings of the English language, deriving from the Greek panax, meaning “all-heal,” and the Cantonese jansam, meaning “man-root.” The troubling image of one’s roots as a panacea will inform the column’s readings of new texts.

*

*

Recently, a colleague explained to me the ubiquity of the subjunctive tense in Spanish, which lends itself well to the magical realism of what-ifs and should-haves inhabited by the speaker. I countered that Chinese has, effectively, no subjunctive tense. I taught bilingual children in Hong Kong some years ago and they would write, for instance: “I wish this poem is good,” and, “If I am a seabird I can enter every apartment window in Hong Kong.” These clauses’ constructions signal no suspension of disbelief. The wish is conjured and, in the next instant, becomes grammatically true. When this nine-year-old imagines herself as a seabird, it is not that she could enter through windows—she already can.

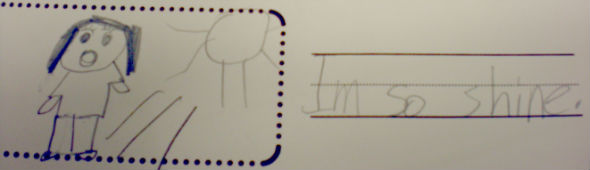

Another of my favorite examples is from a worksheet I gave to a five-year-old. She was directed to draw a picture of herself and use an adjective to describe her mood. She drew herself open-mouthed under the sun and wrote, “Im so shine.” Verbs and adjectives consist of the same words in Chinese and are distinguished only by context or signifiers. That five-year-old’s shiny mood is something which she enacts, rather than something which qualifies her.

In this column, I’ll be exploring how Asian American literature negotiates—whether intentionally or not—the hybrid spaces of a speaker’s multilingual/multicultural consciousness. To begin with, I’d like to provide a taste of Gao Xingjian’s Nobel prize-winning novel, Soul Mountain. This would probably not be considered an Asian American text, but Gao’s political stance as a writer is of interest. Though native to mainland China (where simplified Chinese has been in place for nearly a century), the novel is written in traditional Chinese, in vertical columns from right to left. Its subject matter includes folklore and folk songs, and the many myths and stories from China’s mountain dwellers. Yet these are only a nod to traditional form on the surface; the novel is experimental, highly self-conscious, with a postmodern resistance to character development and linear narrative progression. Gao is working against a Western grammar and influence on the modern Chinese language, claiming a return to a native Chinese syntax. In his essay “Literature and Metaphysics” (transl. Mabel Lee), he writes that “the only responsibility a writer has is to the language he writes in.”

The novel addresses an issue prevalent in China in recent decades: how to preserve one’s cultural identity (an identity defined largely by the tradition of the past) while living in a modern, changing world of overlapping cultures. I have phrased it in this way to show that this is an issue also prevalent among the immigrant communities in America. But what is the language an Asian American writes in? Is it the hip, snappy English of the American present? The formal English of the European past? The diglossic pidgin of the boroughs, the projects, the Chinatowns? The Hawaiian pidgin of those immigrant islands in the Pacific?

Every language is localized and takes its center at the border of another language or vernacular. Every language is a borrowing and an approximation.

How does Gao’s novel demonstrate loyalty to the language he writes in? He centers that language in the subjectivity of the empathic first-person. Each of Soul Mountain’s characters (referred to only as “you,” “he,” and “she”) are inventions of the lonely traveler “I.” Each pronoun has a unique story to tell, at times in communion with the others and at other times completely estranged. The novel is a long series of soliloquies told from different personas of the fragmented “I.” Chinese has no italics and no quotation marks, only brackets for dialogue. When “you” and “she” speak (without brackets), their identities can coalesce so completely that their short lines end with commas—on the page it looks like the poem of a single voice. The narrator takes ownership of the Chinese language by using it as an active process of creation, acknowledging its possibilities and limitations burrowing into other perspectives.

This column will take understanding to be its primary question: how we understand ourselves and others, and what languages or forms of language are used in that process. I hope you’ll partake in this column’s expedition, and that you’ll contribute with comments, suggestions, and discussion.

2 thoughts on “Panax Ginseng: Introduction”