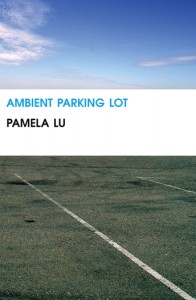

Ambient Parking Lot by Pamela Lu | Kenning Editions 2011 | $14.95

Parked in a corner of Pamela Lu’s Ambient Parking Lot, I turned up the volume on my headphones and listened long past the comfort level of both my bladder and my thirst, testing the limits of the quickly fading sunlight. I chuckled and tick-marked at record speed, drunk with the spot-on parody and ridiculous brilliance of her lines. What I love about Lu’s work is her sharp wit, subtle delivery and deadpan hilarity, which you have to slow down and listen for in order to fully appreciate. Thus, parked, I listened.

Lu’s characters, all of them, are also listening. This book is a mock-documentary novel that tracks the mid-highs and mid-lows of a band of ambient noise musicians, the Ambient Parkers, who record in parking lots and garages and sample car trunk thuds, gridlock traffic honks, revving engines and the like. Aspiring to capture the nature in the machine, their material is capitalism and its doomed, sublime ambience.

Reading this book is like watching an indie webisode spin-off of “Behind the Music” (“Behind the Noise”) run by a group of nerdy, over-enthusiastic volunteers and bored unpaid interns with MFA degrees. Lu tracks the Ambient Parkers’ absolute mediocrity in awkwardly-awesome crescendos and geeky-fantastic loops. Parts of it read like an overly self-conscious, overly detailed fan blog with absolutely no web traffic, which is crafted with earnest, superb engineering and is as addictive as low-calorie reality TV. The band’s fits of self-induced melodrama and cheesy enlightenment register as mere blips and farts to The Alternative Mainstream—yet, anonymously, the band continues, and miraculously, they continue to be heard.

Our album was released in the spring to the deafening silence of the public. Urged on by our manager, we held anemic signings at record stores and granted interviews to lackluster radio personalities, who kept fidgeting in their seats and mispronouncing the titles of our songs. Bearing the cross of those who serve up reality over euphemistic fabrication, we braced ourselves for the onset of poverty that would surely follow our disappointing sales. Our one consolation was the darkness that descended upon our suite each night, relieving us from the sight of our manager combing the want ads and calling our attention to openings for local waitstaff. (125-6)

This book asks us to listen to the intonations between noise and silence, between constant movement and abrupt stillness, between entropy and paralysis, between the cars and the lot. The Ambient Parkers unknowingly stumble upon these spaces, accidentally bumping into other failures of capitalism, other awkward nerds and excessive outcasts. Together they sip weak tea and theorize in a co-op across the street, grappling with their ridiculous and “unspectacular existence[s].” Their refusals—their starts, deletions and restarts—fall like bulldozed trees in a future parking lot, which splinter and crack underneath the bureaucratic electric saw of free-market time. Their attempts beg the question: What does it mean to fail, as J. Halberstam asks in The Queer Art of Failure, if the hegemonic rubric of success is pre-designed?

* * *

Lu brings a boom mic up to the excessive amounts of noise that capitalism constructs and demands be meticulously maintained, from the white noise of gentrification to the mobile phone radiation of global communication systems to the pretentious hype of green trends and the academic elite. If we are often complacent and complicit in these structures, Lu plays back the thrilling complexity of their inaudible sounds and gestures so that we can no longer ignore them. The Ambient Parkers sample and record our sense of worthlessness, insignificance, loneliness and sheer absurdity as artists “superfluous to the discourse” and paralyzed by excess. The “always on” or “always on vibrate” cultural standard means that silence is not something we’re trained to hear.

To train our ears, Lu builds the Ambient Parkers’ profile from a variety of source materials—first in their own manifesto and then in the manifesto of a rival copycat band, the Ambient Barkers. This is followed by “The Salaryman Chronicles,” a hilariously detailed report compiled by a private investigator that documents the bored and empty minutes of a band member who has sold himself out to the corporate cubicle world. We stop to listen to extended tracks: a radio interview with a dancer on her previous collaboration with the band (complete with indications for [Pauses], [Shifts in her chair] and [Forty-five seconds of radio announcements]) and a 50-page email from the Station Master of a pirate radio station who they’ve been stalking (including the band’s ridiculous attempts to reply).

The Station Master, who refuses to play the band’s music on air, chronicles an epic saga from his youth, which includes his blind trek into the woods of “the Orient,” where he encounters a strange creature called Agatha and “hear[s] a new kind of music.” Much of the saga also centers on the rise and inevitable downfall of the Station Master’s lover, Annika, a Swedish opera singer. At a major turning point in her story, she says the following:

When I was singing, all I could hear between the measures was silence—that inhuman silence, the silence of eternity. I often think I must have married that silence before I was born, in some past life perhaps. It’s my one passion, the meaning of my existence. My singing is an attempt to move it and change it, make it turn around and speak to me. My fans mean the world to me and I’ve dedicated my career to them, but I’d give it all up for a single moment alone with that silence, a single moment of recognition. (86)

* * *

The Station Master’s email finally ends in a museum with “a towering animatronic model of a saber-toothed tiger and a giant sloth.” After narrating his journey of global insignificance, Lu focuses our attention here:

The action lasts all of twelve, maybe thirteen seconds. At the end of this time, the cat’s fangs are suspended in midair, less than an inch away from the sloth’s neck. No blood is drawn, no appetite is sated. The inevitability of nature is stalled through human mechanization. Then artifice takes over and the scene is duly reset. With motorized precision, the models slide back to their starting positions. This is perhaps the strangest and most heart-wrenching part of the program, and it is this industrious backsliding, complete with the creaking wheels of machinery concealed beneath the fur, that reminds me indelibly of your music. (119-120)

Caught up in the absurd mechanizations of their lives, the characters in Ambient Parking Lot strive for “a moment of recognition” with silence that is never quite attained or successfully replicated. In their extreme awkwardness, they share an “air of distraction…a restless shifting and quiet shuffling.” They stall; we idle. Our listening stretches out long past what’s comfortable; we listen to them systematically occupy all 116 parking spots in a corporate garage and busk in a park to pathetic results for 21 days.

This kind of prolonged, awkward endurance is embodied by the dancer, who performs an exhausting scene of “experimental torture” inside a wrecked car as part of a collaborative performance in response to events that can be inferred as the aftermath of 9/11. She stretches a 3.5-hour set choreography into a 12-hour improvisation and in effect stages her own death. In her interview with The Radio Host, we witness the traumatic and nearly debilitating effect the performance had on her body. At the end of her interview, she describes a moment of pain (while her friend works on a tattoo) in which she extends through the “miniature trauma site” of her shoulder:

And in that moment of freefall, I understood that I had never really left the car wreck at all. I was still wedged inside the twisted shell, my legs pinned together, a sharp splinter of metal digging into my shoulder. I was dancing, Jerrod’s needle was dancing; we were performing a duet. I was trying to communicate something through each one of my movements. I could feel the pressure of the audience gathered outside, the open-mouthed awe of the musicians as they pointed their microphones at the wreck. […] The musicians are probably still congregated around the wreck, peering inside its jagged openings, documenting the freakish silence with their studious machines. They strain to hear what they can’t hear, to capture what they can’t possibly capture. (174-5)

Everyone in Ambient Parking Lot lingers anxiously in an awkward gear, shifts and shuffles, and conducts their own kind of endurance art. For the dancer to lift herself out of the wreckage, to break through the carapace, is an impossible yet simple act, filled with symphonies of micro-movements and the labor of stasis. In straining to hear what they can’t hear, to capture what they can’t capture, the band is hushed by their inability to replicate stillness’ echo. Lu asks us to open our ears to these auditoriums of absence. She gestures toward the potentiality buzzing in every pause, which waits to be given a voice, to make a move, to become transformed. These moments of emptiness, of realizing something is yet unfinished and missing, are the moments the Ambient Parkers begin to listen for.

4 thoughts on “Review: Pamela Lu’s AMBIENT PARKING LOT”