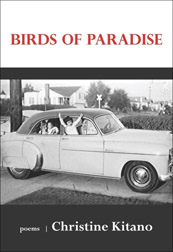

Birds of Paradise by Christine Kitano | Lynx House Press 2011 | $15.95

Birds of Paradise by Christine Kitano | Lynx House Press 2011 | $15.95

“Plain, gray, and though I didn’t / know Latin then, still could guess / what inornatus might mean,” writes Kitano in the closing poem of her collection, referring here to the baeolophus inornatus, or plain titmouse, that flies into her family’s kitchen and is promptly killed. She demands a funeral, identifying with the poor bird:

Plain gray Christine, also known as

the plain daughter, Filia inornata

of the Kitano family. Plain gray

above, paler gray below; crest gray.

The irony of the plain, filial bird emerges when placed in conversation with the title poem of the collection, “Birds of Paradise,” which refers not to birds but to a plantfrom South Africa that looks like the birds. The title also calls to my mind the “false birds of paradise” plant from the Hawaiian islands that looks like the South African plant. I mention all this in order to call attention to the layers of resemblance and recognition—crucial themes to this book of poems. In the title poem, our plain filia inornata cups the bird of paradise plant in her hand, pretending “to be an African queen, the stunning orange / bird my companion, or Sleeping Beauty, / the flower’s sharp stigma a poisoned spindle.” A child of Japanese and Korean immigrants, her marginality and desires push her to imagine a still greater and still more exotic paradise than the one to whichher family has arrived.

In these narrative memoir poems, the search for self is expressed in instances of the estranged and wondrous. Kitano’s project orbits around moments of mistaken recognition, as in the title poem, for instance, which ends with an image of the speaker’s father: “He swam with such power / I almost forgot who he was.” In “Form,” in which the night and morning of her father’s death are condensed into small moments, traces of him are sought after in his stereo set:

White noise hummed

out of the speakers, from which I tried

to recognize a voice. But no, and when

I drew the curtains open, the room filled

not with ash, but light.

This last line evokes misperception to clarify a perception, something we see often in Kitano’s poems. “After the Show” ends with a road that looks like a rope that looks like a river, while clematis blooms look like stars lining that road, which, “From where I stand . . . might be vanishing.” Another poem, “Insomniac’s Best Nightmare,” ends with the speaker waking from a dream during the day: “The sky is still black—not with night, / but crows.” And in “Finding the Family Tree,” the speaker’s schizophrenic brother “thinks [she’s] someone else,” the girls at school “pretend not to know [her],” and:

In the bathroom mirror, under the humming

fluorescent light, behind the face

of my dead sister, I am sad, again

to find myself.

Kitano uses metaphor to collapse identities and associations into one another. In “Bile,” for instance, the speaker’s mother accuses her of being the source of her unhappiness. The poem’s cinematic angle pans back and forth between the silent “I” and the mother who keeps accusing the “you.” Lines are enjambed on the command, “Look,” and the poem ends, finally, with a conflated identity in which three generations are invoked and the words spoken become incommunicable, nonlinear, supernatural:

My mother cries

for her mother, calls out,

her crooked words Korean,

and cryptic as a spell.

Many of the poems are memories of the poet’s father, and chronicle the end of those who are gone or lost. Other poems form a series on insomnia—that state of being half-awake and without a sense of time—and is perhaps telling of this poet’s writing process, as we see in this ending to “Cooking at Night:” “And I’ll spend every night / like this, writing to someone / who sleeps in another world.”

These are also poems in search of wholeness. Paradise is a ghost in these poems, and its imagining is a stupefied act of grasping and remembering. “Untwinned” reaches for a deceased twin, for whom the speaker invents a personality: “She likes the Greek myths, / the flame-breathing chimera / that swallows its own throat.” But this is just a mirror which the narrator keeps under her pillow. The poem ends: “When I can’t / sleep, I practice fitting my fist / into my mouth. It helps me / to feel whole.” These poems are a self-swallowing act, an effort to consume the past, and an impossible effort to close and fit into a full shape. They are poems of lingering and muted absences. “Luis’s Hands” reaches a momentary closeness between two restaurant employees, but ends with the remains of solitude:

That night,

when I undressed,

I found an amber bruise

on my thigh. I pressed

my dry fingers against it

and went to bed thinking

of Luis, the muted smell

of lemon still on my hand.

And these are poems of existing within narrow margins, even inside the household. Here are a few lines from “Drowning:”

I tried to disappear,

invisibility the best defense against

my mother’s anger. I pinned my hair

across my eyes like a fence,

pulled the drawstring

hood of my sweatshirt

tight against my throat.

Disappearance, a boundary, a noose. This poem ends with a dream “of drowning, face to face,” in which the wish to vanish is impossible. One is always seen, or seeing, even if plain and gray.

Birds of Paradise is an apt title for the collection, as paradise exists only in the imagination, always lost or out of reach, much in the same way as nostalgia. And birds of paradise are only resemblances, creatures or plants or people who seem to belong to this out-of-reach space. The poems thus leaveone feeling close and remote at the same time, estranged and yet familiar.

Henry,

Thank you for this review on this book of poems by Christine Kitano, Birds of Paradise”

Your review was immensely helpful for me to better understand those poems.

Irony on irony, subtext on subtext…

I remember one professor of logic ages ago in the 70’s once said to the class, “… And if you didn’t get that, why, the joke is on you.” It appears to me that this time in poetry, we weren’t fully comprehending due to our own lack of insight and appreciation.

So we thank you for your comments on sections of poems that illuminated what is now clearly obvious to us, that we didn’t get it- or poems. Sigh…

Respectfully yours,

Jen