An award-winning Laotian American writer, Bryan Thao Worra works actively to support Laotian, Hmong and Southeast Asian American artists. His writing is recognized by the Loft Literary Center, the Minnesota State Arts Board and the National Endowment for the Arts. He has served as a consultant to the Minnesota History Center, the Council on Asian Pacific Minnesotans and the Minnesota Humanities Commission. He is also an active professional member of the Horror Writer Association and the Science Fiction Poetry Association, and represented Laos as a Cultural Olympian during the Poetry Parnassus of the London 2012 Summer Games. You can visit him online at http://thaoworra.blogspot.com.

* * *

LR: How did you discover poetry and what led you to poetry as a vocation?

BTW:

It wasn’t quite Pablo Neruda’s storied hymn

Of how poetry arrived in search of him. No.

I began at an age some consider very young,

Just a scribble of a soul undrawn to poetry

Until my senior year in Saline High.

One night, like a stroke of spring lightning,

I began to comprehend what verse could do,

What straight narrative could not,

For knot lives of flux best writ with pencil.

My first poem was for a pretty girl in Michigan, a mask.

Something about Batman’s Joker quoting Pagliacci.

Probing unexpected intersections,

I didn’t end up with the girl, naturally.

Still, it was an early lesson.

LR: Your work has achieved much critical success, with an NEA grant among your many honors, but your path to publication wasn’t traditional, in that you were neither an English major nor an MFA student, and your two full-length collections, On the Other Side of the Eye and Barrow, were published by Sam’s Dot Publishing, a science fiction and fantasy publisher, rather than a poetry press. What do you think your non-traditional poetic pedigree has lent to your perspective as a poet?

BTW:

It’s liberating.

I read what I want to read.

I write what I want to write.

That’s a great freedom not everyone has.

I’m humbled to have that opportunity in life.

As a Lao American writer, without naming names,

I didn’t always, sometimes still don’t, get invited to

“Join in any reindeer games.”

Over time, that gave me strength.

“Get my work out there anyway. Any way.”

I push myself to be rigorous, but not hidebound

To one leathery school or dogma.

My writing doesn’t have to be

Safe or conventional as a faithful hound by some sad fire.

I fret not for tenure tracks or professional posts to be happy,

Nor grand accolades or book deals the envy of fading fool Midas.

One dragon summer, I was a cultural Olympian,

The sole writer representing all Lao

During the London games.

Between that and other laurels of yore,

I’m obliged to think

“I’m doing something right, surely.”

But that and a cup of coffee will get you a cup of coffee.

LR: I imagine that, as an experimental multi-genre writer and speculative poet, you are writing for an audience that might be more diverse than the traditional poetry crowd. What do you think are some of the factors that might enable a poet to attract readers who don’t normally read poetry?

BTW:

I empathize with readers who dread

Poetry as it’s been taught to most,

Ones who now fear to struggle with anything

More profound than discount Hallmark cards

In the aftermath of an age of unreadable bards

Who framed baroque texts as some profound thing.

Where are the modern fans of ‘The Raven,’

If not among those who love the alien?

To be sought tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow,

Obscurity is not uninteresting, but let seeking souls in.

Recall: To be read one way correctly once is fine.

If you can be read many ways many times?

Sublime.

Some may object to this meandering course,

Or seek fleeting hype over elegant verse

But time’s a cold, strange scythe regarding

Who’s truly read in the coming century.

LR: You have described On the Other Side of the Eye as primarily questioning the human journey and the importance of empathy. Can you talk a bit about the poetic strategies you employed to explore these questions?

BTW:

Classically, it is said

Upon first contact with the enemy,

The other and the self,

Every strategy falls apart.

Sometimes you get lucky.

The words and worlds fall into place for a second.

Sometimes, you envy the infinite monkeys

Hammering out the complete works of Shakespeare,

In spite of their sad chains, their sad fate

To never recognize how close to enduring truths

They were,

In at least one language of humanity,

Enigmatic in their cryptic, curious expression

Regarding those for which there are no words.

Chapters were composed to challenge.

Routines were inverted, eyes looked outward,

Inward for the infinite, emptiness was reappraised.

The keys include reading widely and connecting freely.

Without, this verse has a veneer of chaos, a shadow war.

Creating a timeless chronicle has many encounters:

Identities fluctuate, you open unique channels and notions,

Content with many scratching heads, often opinionated,

Unique. Now, rummage about for the next riddle and labyrinth.

My mountain is

Not necessarily your mountain.

My story is not your story.

But between

These peeks by the way,

We spy souls talking to souls.

You don”t have to be Lao to wonder in the world,

I don’t have to be a poet to dream,

Truth doesn’t change because of karma or salvation,

Hope endures because humans still ask questions.

LR: Your followup book, Barrow, has been described as an exploration of the question of multiplicity. How do you see this question in relation to the issues and questions you raised in On the Other Side of the Eye?

BTW:

Beyond examining the themes? Extended ruminating.

Words offered revelatory knowledge.

Certainty, rascally and pernicious, provoked you.

Seeking and learning enduring secrets.

Darker than before to illuminate, in Barrow we find

A question of meanings and what makes a word,

What it is, and is not, and how it changes.

In a dictionary, a word is

Defined in a single barebone sentence.

What if you gave a word a whole book to become?

Perhaps we find we gilded a wayward pig’s ear,

Cut thread, or shot at the moon from a hill of the dead,

Wheeled a burden over the horizon or met a pretty heart

Before the end of the world, wondering how to build a boat.

But, even with a whole book to work with,

The last word really wasn’t written.

LR: Both of these collections were published by Sam’s Dot, a science fiction publishing house. What attracted you to them? Can you talk about the experience of publishing poetry with a press that does not specialize in it?

BTW:

Sam’s Dot took a chance with a poet from Southeast Asia

Who had a nascent book of refugees dreaming of the future,

Confronting the ghosts and demons of their past as aliens,

A thousand questions of common ground and uncommon lives.

Tyree was an editor who’d been in Vietnam during the war.

He provided freedom to write what needed words

And let me laugh, remember and dream with ink, opening roads

Of wondrous opportunity.

No questions of italics and requests for footnotes,

Exoticized roadmaps to cultures foreign and fantastic.

A press where Cthulhu and Jabberwocks were as welcome as Lao?

Refreshing. No one stares at you as if you’re insane for telling your story.

And once in a while, you also get a great cup of coffee

When we’re all in town together.

LR: You’ve also had two collections, Tanon Sai Jai, and Sabaidee, Tenessee, published by Silosoth Publishing, which specializes in works by Laotian American writers and artists. Could you please tell us a bit about those two books?

BTW:

There is virtue

In being able to write on your own terms

In your own words your own dreams and songs.

Some call them love letters to a changing nation.

Others, a show of trust that there will be something

For tomorrow’s young Lao and a world where Sabaidee

Is no stranger than

Aloha or rendezvous.

LR: In addition to your full-length collections, you’ve also published two chapbooks—The Tuk Tuk Diaries: My Dinner with Cluster Bombs, and Winter Ink. What decisions do you make in the course of your writing process that determine which projects are meant to be chapbooks?

BTW:

A worthy subject obliges you to write

More words than a soup can label

Or a catalog description of naughty lingerie.

Especially for journeys of friends and family.

Not everything calls for a massive novel

Or even a novellini.

There can be great art in brevity.

You hem in a few topics like Picasso’s bulls

Or Hokusai’s great waving woodcuts of Mt. Fuji,

You might become somewhat immortal.

Or maybe not.

Juries remain notoriously out.

LR: Alongside your prolific work as a poet, you have also written extensively as a freelance reporter for newspapers, including Asian American Press, Twin Cities Daily Planet, and Pioneer Press, and as a playwright, most notably of Black Box, which was performed in New York in 2006; and you have also been an active organizer at SatJaDham Lao Literary Project, working to promote the work of Laotian and Hmong artists and writers. How do you balance working in these multiple genres and professional roles? For example, what does one of your standard work days look like?

BTW:

In this line,

Standard is a misnomer, a unicorn the color of invisible ink.

Balance is a rebus of compromise and obfuscation,

Awash with more “WTH” than “Carpe diem” of late,

Bending time and space on occasion, seizing curious opportunities.

Align all with a laugh, or the cosmos crushes, unrepentant, jeering.

You can ponder a life full of serenity and clean schedules.

Art, however, rarely complies, let alone activism.

Grasp a road, a way, a path and dare deem it concrete and certain?

A gaze at broken plans of mice and men tells all you need to know.

LR: Can you tell us a bit about what you are working on now?

BTW:

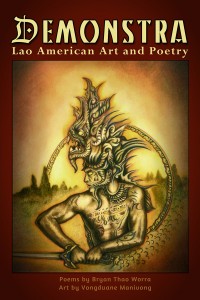

Demonstra is the big thing you’ll see, as I turn 40.

A spiritual update to my older chapbook, Monstro.

Meditations on incomplete demonstrations and miscellany,

Navigating the gulf between what we try to show,

And what we get shown, things we fear, and things we know

Perhaps more than a little

Plus, a new surprise or two, worthy of the Year of the Snake.

* * *

For more by Bryan Thao Worra, see his poem “Pen/Sword” in Issue 4 of Lantern Review.

2 thoughts on “A Conversation with Bryan Thao Worra”