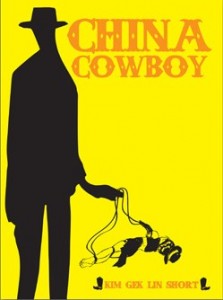

China Cowboy by Kim Gek Lin Short | Tarpaulin Sky Press 2012 | $14

Gross and gorgeous about sums up the Kansas City karaoke nightclub and TECHNICOLOR cinema that is Kim Gek Lin Short’s China Cowboy—all “gorge,” gore and zero pretty. Short’s work is often grossly disturbing and excruciatingly seductive, catching the reader in a tense push and pull with and against the text. Sticky and stuck among the fucking and fucked-up, Short binds us within tales of fierce femme survival as her main character, the feisty and fisty La La, avenges the repeated death of Hollywood’s “dragon lady” with her boots, her mic, and her “country superstar humility.”

Short’s La La reminds me of the scene in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill Vol. 1 (2003) when O-Ren Ishii (portrayed by Lucy Liu) severs Boss Tanaka’s head in front of the Tokyo crime council. When Boss Tanaka expresses his disgust at the perversion done to the council “by making a Chinese Jap-American half breed bitch [O-Ren] its leader,” she runs across the table and decapitates him, without hesitation. She waits for the blood to finish spurting from the cut, re-sheaths her sword, and with Boss Tanaka’s blood on her forehead, calmly addresses the other men:

[in Japanese] So that you understand how serious I am, I am going to say this in English. [re-sheaths sword, switches to English] As your leader, I encourage you from time to time, and always in a respectful manner, to question my logic. If you’re unconvinced a particular plan of action I’ve decided is the wisest, tell me so. But allow me to convince you. And I promise you, right here and now, no subject will ever be taboo. [cut to close-up] Except, of course, the subject that was just under discussion. The price you pay for bringing up either my Chinese or American heritage as a negative is, I collect your fucking head. [holds up Tanaka’s head] Just like this fucker here. [crescendo] Now if any of you sons of bitches got anything else to say, now is the fucking time! [silence, returns to calmer tone] I didn’t think so. [drops Tanaka’s head on table] (O-Ren Ishii, Kill Bill Vol. 1)

O-Ren’s swift and deadly gesture, as well as her sweet and brutal speech, is punctuated by the smiling faces of the only other women in the room, Gogo Yubari and translator Sofie Fatale. Here in a world of men, O-Ren reminds us of La La, who “can fly like they do in chop-chop movies,” “bawl in cowboy” and “lasso a noodle” (17). Just under 5’3″ in cowboy boots, La La is a ferocious folk-singer who headlines as “Patsy Clone” in the Kansas City nightclub from which this book takes its name, a nightclub that becomes a kissing-confessional booth square-dance around her “stab-n-steal” life, stolen death and steely fame.

When she wakes up she has La La’s microphone in her vagina. She knows it is there. She pushes. But the mic is so deep inside her it can’t come to surface. It’s a ship stuck under, she explains, “you were a good mother.” (47)

Short’s nightclub stages the whips and whimpers between voice and ventriloquism, karaoke and clones. Like Loretta Lynn covering Patsy Cline, or Sofie Fatale translating O-Ren Ishii’s speech, or the similarity between the name O-Ren Ishii and La La’s kidnapper/”adoptive father” O’Rennessey (a.k.a. Ren, pronounced run), or Ren speaking in La La’s Waste Me voice, or La La singing into an amped knife—Short hones in on the languages one mouths, or the words one shoves into another mouth. These ventriloquisms of longing punch, flail and grunt throughout the book, yearning to be famous, to kidnap idols and mimic stars.

But the events, installations and recordings that occur within China Cowboy are far more weird and traumatic than I’ve let on. It’s full of patsies who are repeatedly taken advantage of, cheated and blamed. Short deals with very real and very scary stories of child abuse and kidnapping and the creepy workings of pedophilia. Yet through this, we know that “La La, dead or alive, always wins” and she reverberates, vibrates, giggles and yells her way through this book. She throws her voice in all kinds of directions, and to all kinds of destinations, from Hell to Hong Kong, from Fist City to Kansas City, from Kansas to Kowloon. And in whatever position we find her in—handprint burned to her ankle, “insect-pushed” (92)—she never stops thrumming.

I weave her out and she wakes up. She rubs her eyes and then holds her hand out to me. She wants her microphone. It is buried and I shovel off dirt to get it. It is dark and I have to feel us up to find it.

For a moment I think it might not be there and I panic. But then I feel it. I give it to her.

In her mouth now and for some reason sleeps that way, sucked all in, “because that is how we all knew her after all.” (67)

Microphones are brought to the mouth and to the cunt. The object that is meant to amplify the voice is always swallowed. La La’s mouth shifts from wailing to sucking, sucking to eating, eating to singing, singing to swallowing. La La and Ren dig at each other, trying to find a grip on the other body. Breaking and brokenness and affective longing are thrown up and jammed into La La’s voice—a voice that is “cuntry” music. Her sustained frequency—like a constant radio broadcast—boils, bubbles and queefs its melodies, mimicking her “impossible” or “comedic” or “ridiculous” racial enjambment of “chink” and cowgirl, “y’all” and yellow.

That noisy jam finds itself in the form of Short’s poetic prose, which is full of run-on sentences with missing commas, as well as shutter-stop stutters. For example: “She fixes her rigor mortis on my hands clamps she is driven my strada but I pry at her” (75). Two or more sentences are often jambed together, or phrases parse themselves in rapid succession like knots. These rhythms reveal gaps and expose the stressors and traumas of the text. Short’s syntax mimics La La and Ren’s knotted relationship, “like vowels in the middle of ending” (58) that “[shoot] from her gut for several highway exits” (56).

The little girl goes limping down the back road not alone. A truck pulls in front of her it emits punch-bright. The little girl gets in the truck her boots start melting. “Hell is a hot place,” the radio hisses, “get off your feet.” She puts them on the dashboard the soles go liquid. She tilts a broken bottle to catch the bootjuice it slips sledding down the dash clump-heavy. The little girl thirsty cuts her lip on the broken bottle. The juice gets boiling. She seeps scorching. Her boots clot-thick crackling her loudest song left. (“Hell” 14)

The “vermicelli” western aesthetic of this book plays out in La La’s karaoke Cline clone and her visions of Clint Eastwood. La La says, “In my sleep I am starring in Coal Miner’s Daughter. I am as convincing as Sissy Spacek except I am Chinese and just can’t help it. I can’t” (27). She could also be an Asian Sissy Hankshaw hitchhiking with enormous thumbs in Even Cowgirls Get the Blues. Or Laloo and the color red in Bhanu Kapil’s Incubation: A Space for Monsters (Leon Works 2006). I see some of La La in the star-crossed lovers Rumpoey and Dum in the “pad Thai” western Tears of the Black Tiger (Fah Talai Jone, dir. Wisit Sasanatieng, 2000). Rumpoey, played by Italian-Colombian actress Stella Malucchi, throws her Thai voice against her non-Thai ethnic background as she stares, lovelorn, into the distance (very Thai), while over-saturated colors, painted likay backdrops, fake blood packets and her lover Dum (a Thai assassin-cowboy playing a harmonica) burst like soup dumplings behind her.

The performative aesthetics of gore and violence in these films—from O-Ren Ishii’s femme deadliness in Kill Bill Vol. 1 to the over-saturation of colors and blood and parody in Tears of a Black Tiger—are siphoned, reassembled and re-sung as karaoke covers in the TECHNICOLOR screenplay of China Cowboy. Through the small-framed but indestructible body of La La, Short utilizes a poetics of excess (an over-saturation of sex, secretions, child sexuality, pedophilia, country music and murder) that intervenes on popular representations of East Asian “femme fatales” and on the white American male’s fetishistic desire for this kind of deadly Asian girl, even if it’s only a costume or role-play. I’m thinking here of Street Fighter video game character Chun-Li, or Knives Chau in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. The trauma induced by a repeated eroticization and fetishization of these bodies by white men (who mark them as Asian, female, deadly, sexy, other, and reduce them to objects in porn, feature films and video games) is avenged by La La’s persistent screaming/singing as she re-fashions her crooning into a weapon. No matter who is preying on her or picking her up, no matter how many times the white devil leaves his mark upon her body, the desire and pleasure is always hers.

China Cowboy‘s coda includes a series of Ren’s paintings installed in his Soyabean Gallery. Each plate has a duration; their dimensions are indicated by days and hours. Here the text is smeared across the page and down. It’s a catalog of missing children; it’s a handful of beans. La La is in the evidence collection while everyone else’s plans are permanent. X! X! X!—a cut or footnote, high ten in the hands, triple x. A gunshot, a target, a variable. We learn that there are three La Las. Are they sisters or clones? Mothers and daughters? William O’Rennessey splits into Bill and Ren. La La splits into Pet and Patsy Clone. Dante, boss and Baba. As the evening comes to a close with La La’s songbook, our little girl is “last seen “and “the last scene,” a secretion other than vulnerable. Even through “assgulp strangling” (22), she’s a song we can’t get out of our heads as we remember “how killing / didn’t/couldn’t / Squish her” (92).

Interesting review. I contextualized China Cowboy differently but that’s just proof that the book holds up very well to various scrutinies. Here’s my brief take on it as I posted it at Goodreads:

China Cowboy is an indeterminate prose work that veers toward story telling. Non-linear in that it ricochets back & forth between 1989 (when the heroine/victim La La is 12), 1997 (when La La is either 20 or dead) & 2001 (when La La’s story has become myth, at an exhibition at Soyabean Gallery, when La La herself is dead or alive). One could say that La La is both dead & alive throughout. The setting is America set in Hong Kong, that pulp town par excellence. That La La’s parents support themselves through a combination of prostitution & picking up tourists stranded during hurricane weather, then murdering them & stealing their luggage is apropos, since Ren is one of these typhoon-tourists. He survives to return as the American cowboy cum soybean farmer cum artist cum rapist cum pedophile. From the top, the story of La La & her abductor Ren (aka Run aka William O’Rennessey) recalls Lolita & Humboldt Humboldt, as it must. It’s not just La La’s name or age. The violation that is violence, or vice versa, is more overt in China Cowboy & the prose is not the perfect English sentence of Nabokov (which I find suspicious), but rather its antithesis. China Cowboy trumps Lolita in that La La gets out more alive than dead, even if she is really dead. Lolita survives but as the living dead. La La is the more compelling presence, perhaps because the story is told from both her & Ren’s perspectives, so that the tables are at least turned 90 degrees (La La is still, it’s important to note, a victim, no matter whether or not she “wins” in the end). I imagine La La giving Nabokov the finger, perhaps both in homage & in defiance. I may be creating my own text in thinking of La La this way. For all I know, Gek Lin Short adores Nabokov. But La La has agency in a way that Lolita does not. La La can get up on the table & sing. Her imitation (Clone) becomes something new. Her victim identity is not all she is. Nevertheless, she is dead & gone, or she splits into three: dead, alive, gone. Ren, differently, splits into two: Ren & Bill. But Ren & Bill are one & the same in a way that Pet, La La & Patsy Clone are not. China Cowboy also brings to mind Alice Notley’s feminine epics, Descent of Alette & Disobedience. Both author’s reference Dante in creating their heroine’s journeys. And Gek Lin Short’s Ren /Run, Clint Eastwood, Patsy Cline/ Patsy Clone reminded me of Notley’s Hardwood/Hardware/Hardwill; Mitch / Robert Mitch-ham / Dante Hardone, etc. China Cowboy is in keeping with other books on the Tarpaulin Sky list in that it has a transgressive nature. Trangress away!

Many, many thanks to the folks at Tarpaulin Sky for this lovely nod! And congrats to Kim on the Blurby Award!

Hi Paula! Thanks for sharing your review here. I resonate with the ways you see La La as trumping Lolita and getting out more alive than dead, or living dead, and her agency, yet the shakiness of that line–victim or victor–and the shakiness of the location of “agency” itself. Interesting also to note the perfection of Nabokov’s prose versus the dirty gritty of Short’s language and how her language and syntax mirror the living dead agency of La La. Thanks again for these inquiries!