Esther Lee has written Spit, a poetry collection selected for the Elixir Press Poetry Prize (2011) and her chapbook, The Blank Missives (Trafficker Press, 2007). Her poems and articles have appeared or are forthcoming in Lantern Review, Ploughshares, Verse Daily, Salt Hill, Good Foot, Swink, Hyphen, Born Magazine, and elsewhere. A Kundiman fellow, she received her M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Indiana University where she served as Editor-in-Chief for Indiana Review. She has been awarded the Elinor Benedict Poetry Prize and Utah Writer’s Contest Award for Poetry selected by Brenda Shaughnessy, as well as having been twice nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Ruth Lilly Fellowship, and AWP Intro Journals Project. Currently, she pursues a Ph.D. in Creative Writing and Literature at the University of Utah and lives with her fiancé, Michael, and their dog and three cats in Salt Lake. Starting this fall, she will begin teaching as an assistant professor at Agnes Scott College.

This April, we are returning to our Process Profiles series, in which contemporary Asian American poets discuss their craft, focusing on their writing process for an individual poem or poetic sequence of theirs. As in the past, we’ve asked Lantern Review contributors to discuss their process for composing a piece of theirs that we’ve published. In this installment, Esther Lee reflects upon the excerpt of her project Daughters of Celluloid that appeared in Issue 5.

* * *

(if his plate would not record the clouds, he could point his camera down and eliminate the sky)

—John Szarkowski

If there is a hegemonic familial gaze, imposing rigid familial ideologies, then mothers are most cruelly subjected to its scrutiny.

—Marianne Hirsch

Excerpts of this Process Profile are pulled from a craft talk titled, “Double Exposures: Photographic Fictions and Traumatic Memories” given at Virginia Tech. All photographic images are ones I’ve taken or borrowed from family albums.

Excerpts of this Process Profile are pulled from a craft talk titled, “Double Exposures: Photographic Fictions and Traumatic Memories” given at Virginia Tech. All photographic images are ones I’ve taken or borrowed from family albums.

My hope is to invite you into a constellation of influences—and mostly questions—I’m working with and exploring in this work-in-progress, tentatively titled Daughters of Celluloid. This constellation includes the works of writers and artists who meditate on, thematize, and/or employ photography, as well as those whose works investigate the complexities of trauma and representations, in particular, of trauma not directly experienced first-hand. So a kind of assemblage, if you will, one that is part wax, part string, part etched glass.

In Daughters of Celluloid, the narrator finds that her mother’s enigmatic past is pocked with speech, presented as fragmented anecdotes, suggesting recessed narratives of trauma and dislocation. To borrow a phrase from the French novelist and Holocaust writer, Henri Raczymow, memory is “shot through with holes” and underscored by potential absences of family photographs wherein large swaths of time and space have seemingly vanished, losing any semblance of continuity. As a result, the narrator finds herself attempting to photograph the mother, grappling with how the camera can both fix and unfix them. In doing so, they disrupt their unspoken ways of looking, complicating the myths of familial memory and, ultimately, searching for what Alison Bechdel describes in her graphic novel, Are You My Mother?, as a “mutual cathexis” between mother and daughter, wherein they can recognize each other’s invisible wounds.

* * *

WAX.

What I know about this photograph:

This is my mother. Or an image of her. Though she is questionably small. Though her face is a blurred coin without face or denomination. I tell myself that this is my mother. That I belong to her.

If you squint, my mother appears to be an extension of the tree. Or the tree an extension of her. Either of which: an aberration of the other. I’m unsure how far the shadow extends.

My own vision is terrible, especially my left eye. As a child I was encouraged by a well-meaning optometrist to read with a cutout piece of newspaper taped over the left side of my eyeglasses. All in the hopes of correcting my vision. Eventually, I ripped it off.

* * *

STRING.

Barthes’s Camera Lucida is perhaps (next to my fiancé) the love of my life—the book, that is, not Barthes himself, although I should re-examine this possibility too.

In the aftermath of his mother’s death, Barthes searches though photographs of her, photographs that would, as he puts it, “speak” and allow him the hope of “finding” his mother again.

He writes:

I never recognized her except in fragments, which is to say that I missed her being, and that therefore I missed her altogether. It was not she, and yet it was no one else. . . . Photography thereby compelled me to perform a painful labor; straining toward the essence of her identity, I was struggling among images partially true, and therefore totally false (65-66).

A few pages later, Barthes describes a photograph of his mother as a child. She is standing with her brother at the end of the little wooden bridge in a glassed-in conservatory. This “Winter Garden photograph,” as he refers to it, is the photograph which allows him to feel that he has “at last rediscovered [his] mother” (69).

Unlike Barthes, however, I’m unsure of what a photograph of my own mother as child would look like since there are none in our family albums. Instead, photographs of my mother begin mid-sentence, mid-narrative, in her thirties, as if her infancy and adolescence had somehow never occurred.

* * *

GLASS.

There are too many photographers from whom I draw inspiration to name here, but I’d like to highlight a few below.

Like a social anthropologist or a driven method actor, Lee observes particular American subcultures and ethnic groups—such as punks, yuppies, skateboarders and swing dancers—and adopts their customs and costumes through gesture and posture. In her “Projects” series, she immerses herself in the respective lifestyles of these groups, a process that sometimes takes weeks or even months, which involve performing and posing in snapshot photographs, doing basically whatever it takes to “fit in.”

Her ability to “perform” cultural identities in these photos suggests that identity is not a static set of traits belonging to an individual, but, rather, something constantly changing and re-defined through relationships with other people. She’s been described, not surprisingly, as a chameleon. Her work often unnerves viewers because of its ability to provoke questions of authenticity and sincerity, sometimes revealing our own assumptions and stereotypes about cultural identities.

Lee’s work informs my own attempt to consider the ways our identities can be reconstituted, how identity can be an arena of free play, where appearance may serve only as an alterable mask. In my own work, markers of ethnicity and race are destabilized. For instance, the mother character purposefully thickens her Korean accent to avoid receiving a speeding ticket. Moments when ethnic markers are acknowledged—and are in danger of aesthetically commodifying Asian American cultural differences—attempt to give way to other moments that obscure and discomfort those conventional boundaries and subjectivities.

* * *

WAX.

Bertien van Manen is a Dutch photographer who has traveled extensively in Eastern Europe and Asia, often learning the native languages and developing bonds with people she has photographed. In one series, she took photos of people’s photographs instead of photographing the people themselves. In a video about her work, she mentions that when she’d visit people’s houses, they’d ask her, “Where do you want me?” and she would respond with, “I don’t want you. I want your pictures.” At times van Manen would arrange the photos in the person’s home, juxtaposing the photo with a particular object belonging to the person who lived there. Her photos often suggest the impact of larger cultural memories—at times those memories have alluded to traumatic events such as the Holocaust or other upheavals—on personal, private lives.

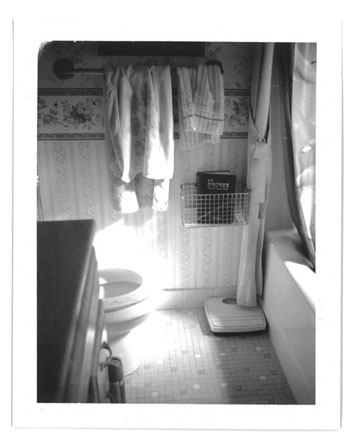

Her photographs speak to my own interest in photographs as cultural objects loaded with meaning and ideologies. I’m interested in portraiture via photographing of spaces (both with or without photographs in them) and what these spaces could illuminate about a person, perhaps as much—if not more so—than a conventional portrait of their face.

* * *

STRING.

The American photographer, Nan Goldin, says that, when she was a kid, people would tell her that “You didn’t see that, that didn’t happen,” so they’d tell her what she’d experienced for her (instead of believing her perception of reality). As a result, she became skeptical of other people’s versions of reality and started taking photos. She says, “It was all about keeping myself alive . . . about being able to trust my own experience . . . I still use the camera as a tool of anti-revisionism.”

We can see just how urgent such a statement is when it comes to one of Goldin’s most memorable photographs’ title, Nan one month after being battered (1984). In using the camera as a tool of anti-revisionism, Goldin suggests that this photograph of her bruised face following a beating from a former lover possesses a documentary authority that she can’t (and doesn’t want to) deny, evidence that prevents her (as she suggests) from ultimately returning to an abusive relationship.

Her compelling statement, however, provokes one of the major questions I’m exploring in Daughters of Celluloid, which is whether photography may offer a way to actively revise the past, potentially bringing to light how we are constituted in the space of social configurations like family. For instance, how do we look at, see, scrutinize, survey, and monitor within the institutions of family? What happens to the family’s visual interactions when the coded nature of family photos are manipulated, purposefully distorted, or re-enacted?

* * *

GLASS.

Sally Mann’s controversial photographs of her children (exhibited in 1992 and later published as a book titled, Immediate Family, in 1995) explore familial bonds, as well as maternal love and child response. The photographs of Mann’s children seem to meditate on the concept of childhood and “growing up” using a variety of the sensual, the everyday, and the fantastic; all through a maternal eye.

It’s important to note that plenty of critics have argued that this body of work evokes cultural anxieties. Mann emphasizes, however, that she herself didn’t intentionally seek to provoke those anxieties. She states that these photographs are simply “of my children living their lives here too. Many of these pictures are intimate, some are fictions and some are fantastic, but most are of ordinary things that every mother has seen.”

With regard to Mann’s work, I’m most interested in how her photographs ride the line between the particular and universal, between fiction and authentic experience, while not shying away from the nostalgic or the taboo. Her work also incorporates a sense of performance in that she at times stages elaborate portraits that still lie within the realm of possibility, at times re-creating actual events.

For instance, in the case of her photograph, “Jessie Bites,” Mann explains in the documentary, What Remains, that her daughter Jessie had bitten her, but by the time the photograph was ready to be taken, the bite mark had all but disappeared. As a result, Mann recreated the scenario by creating the bite mark on her arm herself.

* * *

WAX.

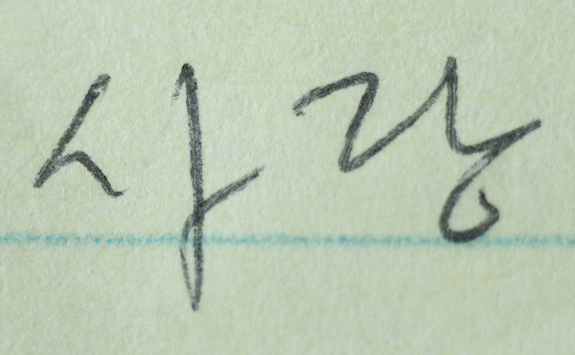

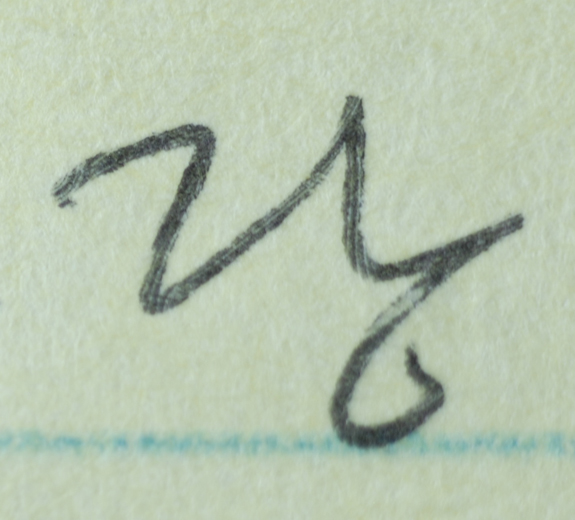

Here is a close-up of the word “salang” in Korean, which means “love.” This is lifted from a letter written by my mother.

And here, an even closer view of the syllable, “lang.” To consider my mother’s handwriting and ironic notions about the ways we look at and scrutinize each other, I created a letterpress broadside, which centers around this second syllable, “lang.”

* * *

STRING.

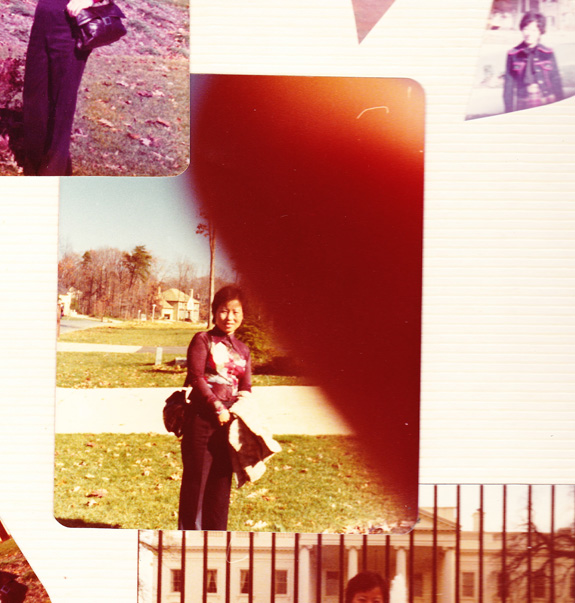

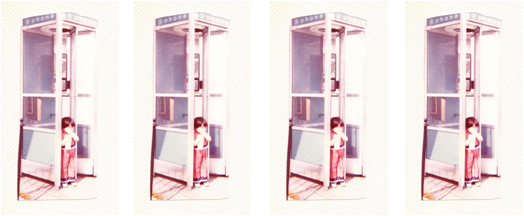

The window—heightening my awareness of her torso—threatens to weigh down her shoulders, to startle her. On the other hand, the window (it could be a helpful window!) might serve as her thought bubble. Though what is visible is the bubble and not her thoughts.

What is disconcerting is how the tree in the background horizontally distends, that perhaps I inadvertently (and digitally) stretched its branches—and the framed world—apart. I feel guilty but don’t correct it.

I don’t understand why everything is so magenta. Perhaps I am to blame for this too.

The house behind her is not ours.

The boy’s face I cropped out may belong to one of the children my mother took care of. This may be their house. The trees suggest an affiliation between them.

* * *

GLASS.

Lyrics from Bill Callahan’s song, “Night”:

We do not know how things work

We do not know where you go

In the night

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

We do not know

The door that holds you

Silent as glue

We stand under it

But we don’t understand it

We stand under it

But we don’t understand it

The door that holds you

Silent as glue

These lyrics evoke my own sense as a child of a palpable silence within my family. At times these silences seemingly culminated in overt physical violence and in other ways, symbolic and subtle. Henri Raczymow writes, “The unsaid, the untransmitted, the silence about the past, were themselves eloquent,” and yet “fragments have been transmitted . . . a trace remains.” My parents were children during the Korean War. What they had experienced during that time has been offered in slivers, alluded to or mentioned as fragments during conversation.

My parents’ testimony, if you will, arrives, sparse, out of context—like slips of paper, creased against the grain, waterlogged, and baring cryptic scrawl. A curse? A folded love note? As Jeanette Winterson said during a recent reading, “The words are the parts of silence that can be spoken.” Familial legacy: itself both gift and debt. We stand under it, but we don’t understand it. Silent as glue.

* * *

WAX.

In Immigrant Acts, scholar Lisa Lowe votes for what she calls a “horizontal generational model of culture” in which cultural identity is constantly in flux, never complete, and considered in relation to history and power, rather than the vertical anthropological model wherein cultural identity is fixed and related to some essentialized past. For Lowe, interpreting Asian American culture exclusively in terms of the master narratives of generational conflict and filial relation essentializes Asian American culture, obscuring the particularities and incommensurabilities of class, gender, and national diversities among those of Asian descent.

In Daughters of Celluloid, however, rather than to opt solely for this horizontal model as Lowe recommends, I attempt to revisit and possibly rearticulate this vertical model of first/second-generation struggles, wondering how/if the portrayal of these generational conflicts and filial relations can avoid the former representational pitfalls of reducing social differences into a solely privatized familial opposition. How might this text celebrate a paradigm based more on heterogeneity, hybridity, and multiplicity, revealing how the making of Asian American culture includes practices that are partly inherited, partly modified, as well as partly invented? In other words: part wax, part string, part etched glass. And, more broadly, how can writers of color potentially avoid re-inscribing the very demarcations they admonish and find reductive, yet celebrate and foster the sense of alliance and empowerment that collective identity constructs can spark?

* * *

Understandably, there are conflicting theories about the notion of an “intergenerational transmission of trauma”—from whether or not trauma can actually be “transmitted” (and to what extent), to questions of how to even refer to the children or their parents who have survived trauma.

While my aim in Daughters of Celluloid is to not necessarily align with a particular viewpoint (at least not wholesale), instead I wish to explore the complications of varying viewpoints (at least in sections of this work and in oblique ways) and put them in dialogue with one another in this manuscript.

Take for instance, Kaethe Weingarten’s investigations about how the trauma of political violence experienced in one generation may “pass” to another generation that did not directly experience it. This “intergenerational transmission of trauma,” according to Weingarten, may result in what she calls “secondary” or “vicarious traumatization.”

Ernst van Alphen, on the other hand, in his article, “Second-Generation Testimony, Transmission of Trauma, and Postmemory,” questions the alleged continuity of trauma between generations, which is implied by such terms as “second generation.” He writes, “it makes little sense to speak of the transmission of trauma. Children of survivors can be traumatized, but their trauma does not consist of the Holocaust experience, not even in indirect or mitigated form. Their trauma is caused by being raised by a traumatized Holocaust survivor.”

In her book Family Frames, Marianne Hirsch describes what she refers to as “post-memory,” which “characterizes the experience of those who grow up dominated by narratives that preceded their birth, whose own belated stories are evacuated by the stories of the previous generation shaped by traumatic events that can be neither understood nor recreated.”

Along with the ways in which trauma is potentially suppressed or “transmitted” through verbal and non-verbal, symbolic means, I’m interested in exploring those seemingly invisible networks of looking, concentrating on a single family and the role of their family photos as a form of imagetext that mediates individual and familial memory.

Bertien van Manen’s work also relates to what Marianne Hirsch refers to as the “unconscious optics” of familial memory by provoking us to question the ways in which we are constituted in the space of family through looking, how power is deployed or contested. Through narratives mediated by the daughter in Daughters of Celluloid, an unreliable transcriptionist/archivist of both her personal and familial histories, how might concealed optical relations resurface and become acknowledgeable? How are traumatic events potentially negotiated, framed, and reframed?

* * *

GLASS.

To explore the tension between the use of the camera as an anti-revisionist tool (as seen in Goldin’s work), as well as the possibilities of photography as a revisionist tool (as suggested by works by Cindy Sherman and Nikki S. Lee), or more broadly, the tension between what is potentially decidable and undecideable with regard to individual and collective memory, a kind of ‘double exposure’ is evoked. In a sense, a superimposition of both familial inheritance and political trauma, of both gift and debt, of remembering and forgetting, of the dual impulse to both fictionalize and to document. In a later section of Daughters of Celluloid, the daughter and mother characters broach new territory in their visual interactions. Through the re-enactment of former events, they intervene by “performing” photos, thereby “unfixing” their former meanings, which may allow for new ways of seeing each other.

* * *

WAX.

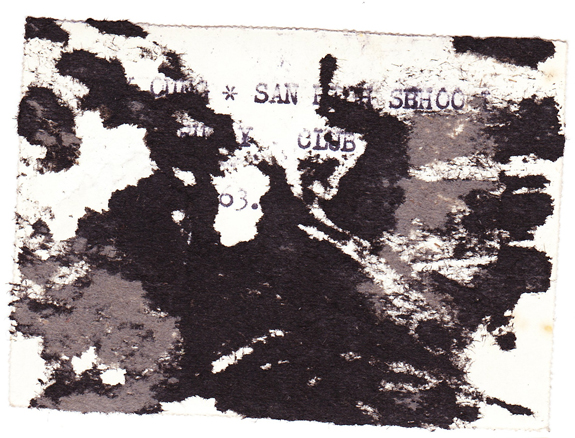

Often, photographs, for me, suggest silences. Visual reminders of the very factors that help create an archive of elisions. Even the backsides of certain photographs (as this one below from a family album) are also emblematic and resemble that which shapes our own sense of belonging: maps, eruptions, frames, chromosomes, fingerprints, signatures—presences both inscrutable yet familiar. How to make sense of what Nadine Fresco calls a “diaspora of ashes”? Perhaps this is why I search for and collect old photographs from antiques malls, thrift stores, yard sales. And at the risk of committing what Susan Sontag would consider a dangerous collecting of the world, I love to stare at these familiar and anonymous faces in photographs, whether they belong to my own family or someone else’s.

Much of what fascinates me most about these artists I’ve mentioned (and others like Philip Lorca di Corcia, Sophie Calle, Duane Michals, etc.) is how their work at times problematizes two (arguably) divergent modes of photography—as a possible realm of fiction and duplicity, as well as a medium devoted to authenticity of someone’s perceptions and experiences.

This is very interesting, thanks for posting!