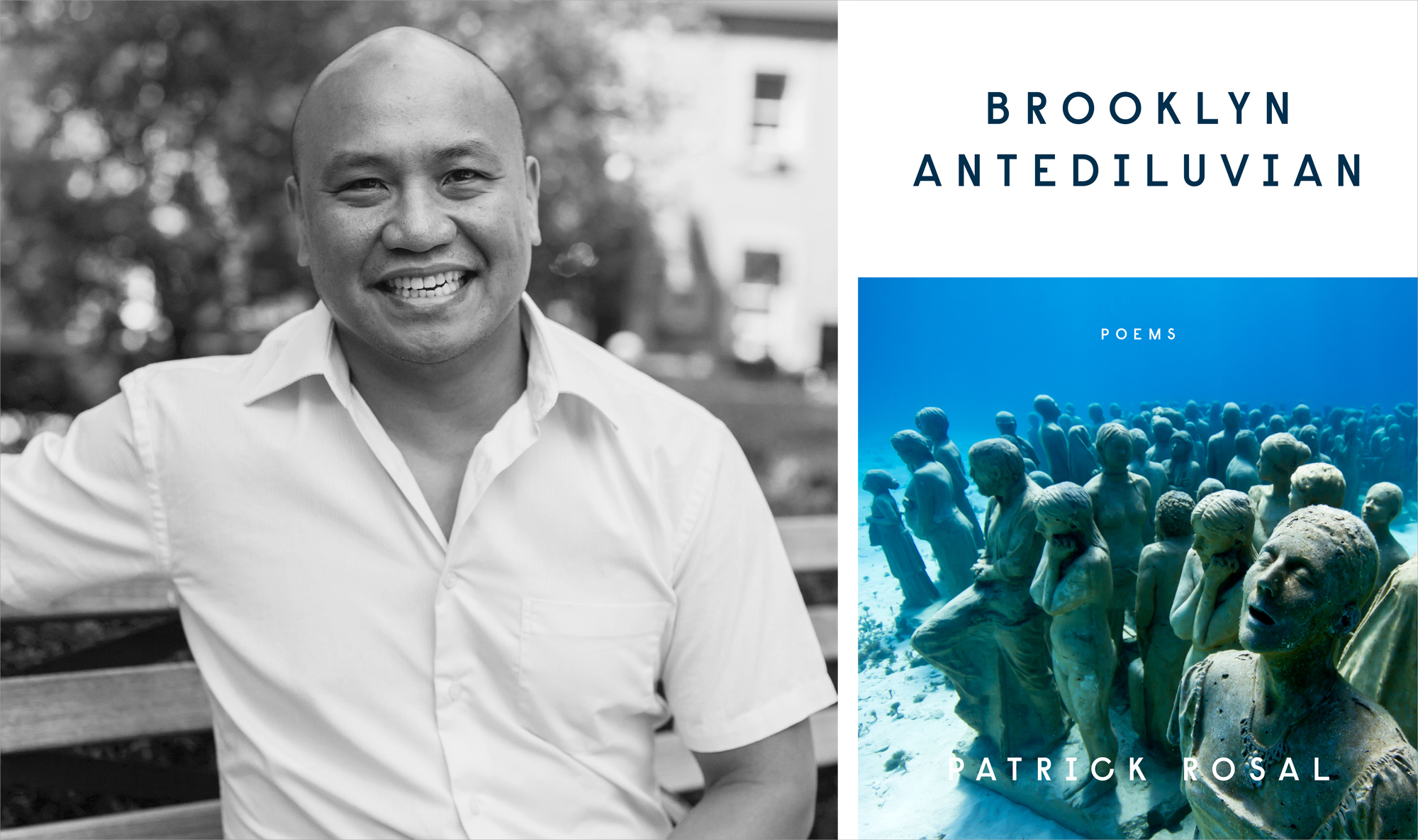

This month, we were delighted to have had the chance to converse with poet and professor Patrick Rosal about the recent release of his fourth collection, Brooklyn Antediluvian. In our discussion, recorded below, he reflects on the themes and mythologies that shape the book as well as on the publishing process and the influences that music and young people have had on his work. (For yet more on Rosal’s process and inspiration, you can find our previous interview with him here.)

* * *

LANTERN REVIEW: In Brooklyn Antediluvian, water is a central motif. It serves as a force that sweeps the movement of the collection along and is a metaphor for the violent submersion of identity enforced upon the colonial subject under the auspices of imperialism. How did you come to settle upon this motif? Why water, and what was it about the image of destruction by flood that compelled you?

PATRICK ROSAL: First, thanks for reading the book and doing this interview. I feel real lucky to have Lantern Review make space for this new collection.

Growing up in New Jersey, we were always in and around water. And I think we have a special relationship to water as Filipinos in America, having been the descendants of monsoon rains and of people who had to cross miles and miles of water (my grandfather was a sakada, a sugar laborer who sailed from Manila to Hawaii for work). Also, I have real specific memories of water—like my brother almost drowning when he was a toddler or the image of me and my cousins heading out to the Jersey shore mid-week to dive into the waves. And then there were the storms like Katrina and Ondoy and Sandy all in a relatively short period of time, each of which touched me in very personal ways. At some point, probably after I got a sense of the title poem, “Brooklyn Antediluvian,” I realized this book was going to be about waters and floods—which is to say, literal floods from those storms, but also the floods of memory, of roses, of violence, of joy, of names, of gentrification.

LR: The collection draws its name from the final piece in the book, a long poem that commands nearly a third of the text. What appeals to you about the long poem as a form? What was the process of drafting this particular long poem like for you, and what motivated your decision to structure the collection in this way, with the shorter poems up front and the long poem as a finale?

PR: My poems have been getting longer over the course of my four books. In Boneshepherds, I had a poem, “Ars Poetica: After a Dog,” that felt massive, and in a lot of ways it’s a heftier poem than the title poem of Brooklyn Antediluvian, though the more recent poem is a lot longer in terms of pages.

In “Brooklyn Antediluvian” I loved having enough space to make things disappear and then suddenly show up again. I loved getting lost as I was writing because the language kept leading me away from any static subject. And just when chaos might take over, some small connection to a previous image—a rose or horse or name or the boy whom the speaker meets in the first line—would come back. It’s a different kind of lostness from [what you might find in] a short lyric. It’s a study in departure. Also, it gave me a big enough world that many histories and continents—especially in small narrative scales—could exist in the same text. All of this, for me, is a metaphor for seeing and living. I want to see if it’s possible to build a world in language that accommodates epochs and landscapes that seem to have nothing to do with one another. This seems to be the source of a lot of our trouble—parts of our world are so belligerently segregated from one another. What does a Berber pope have to do with a Filipino dietician who died in New Jersey, anyway? A long poem doesn’t just reveal those unusual and often wonderful associations, it finds a music—a pleasing sonic pattern—with which to connect them.

When I first started compiling the poems I wrote after Boneshepherds, I felt a real strong impulse to make a book that could still reach people who don’t consider themselves poetry readers. When I drafted the long title poem, I knew I had something that was going to be challenging even for audiences that consider themselves aficionados of contemporary poetry. I sent the manuscript out to friends, and they made it clear to me that I needed to set up a world of images, places, figures, and rhythms to help prepare the reader for the long poem at the end. Originally, I had the long poem at the front of the manuscript. In the final version of the book, [in which the poem’s at the end], I think readers have a stronger relationship to the ways of looking and singing that the title poem tries to sustain for a longer period of time and on a much bigger scale, with much trickier leaps.

LR: Traditionally, the term “antediluvian” refers to the period before the Great Flood (of Noah’s ark), a time that is partly notable in Biblical accounts because the mythical is said to have coexisted with the everyday—people lived for centuries and humans married “sons of God” who walked the earth. Your modern antediluvian account, too, interweaves realism with a rich mythological world of your own invention: among other tales, there are the creation-flood-survival story of “Fable of a Short Song”; the account of Josefina and Filomena in “Instance of an Island”; and the saga of the old woman in “Brooklyn Antediluvian” who, Methuselah-like, lives long enough to remember the name she had before it was taken from her by colonizing powers. As a poet, how does the interplay between myth and history inform your understanding of narrative possibility and your approach to craft? How did the distinct mythology of this collection come into being in your imagination, and what was the process of fleshing it out on the page like?

PR: I’m so proud of that mythical strain in this collection—and really throughout my work. I don’t think most people would really think of me as someone who deals with myth, but I love the fantastic. Also, growing up Catholic, we were taught through parables, allegories, and the startling and violent imagery of the Passion. I’ve always been fascinated with the challenge of writing a book that incorporates elements from memory or observation with images, fragments, and stories that are invented or highly imagined. I often marvel at the terror and beauty of my dreams. When I wake up, I don’t always remember them clearly, but certain images persist, and more than the imagery, the emotional and psychic impression they make can last the whole day or longer than that. The lyric imagination of a poet can tap into the same experience.

“Antediluvian” is a pejorative term, but it acknowledges that there was a Brooklyn before the rather expensive and fashionable version that we have come to know in the last decade or two. There were many Brooklyns, including the one that my father knew in 1965, when he was a priest in Williamsburg at the Church of Saints Peter and Paul and delivered homilies to the Puerto Rican workers of the Domino sugar factory. I’m not interested in historiography the way a scholar is, but the facts of history are extremely useful to me. In “Brooklyn Antediluvian,” I’m not trying to construct a narrative exactly; I’m trying to write a song. I’m trying to compose a very long orchestral piece made, yes, out of the facts of history, out of the names and words of history, but more importantly, I’m trying to uncover connections by following the music those names and words suggest. One of the things I’ve always loved about poetry is its ability to suggest a coherence that you can’t always define or explain. A sound or image can appear, disappear, recur, and change. Like music, a poem’s transformations and movements—of sound and image—make a meaning that is infinitely more important than the action, plot, or drama that the poem ostensibly represents. I hope that makes sense, but the myth and narrative are just another ordering strategy for the music of the language.

LR: Young people play an integral role in Brooklyn Antediluvian. From the speaker’s niece in “Ten Years After my Mom Dies I Dance” to the middle schooler whose passing remarks become a launching point for the titular poem—the fragile bodies of children, as well as their voices, are crucial agents that move through and heighten the stakes of the collection. At times, you write from within a child’s worldview (as in “Ode to Not Having Enough Kids to Play a Game of Baseball”), while at others, you tap into the perspectives of adults assigned the responsibility of protecting children (as in “Typhoon Poem”). Why was it important to you to interweave the viewpoints of children (and especially of children who are being taught to survive by the adults around them) so closely into the fabric of the collection? As a teacher, have you found that your work with young adults in the classroom, especially in the wake of recent high-profile acts of brutality against children of color (Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, and others), has shaped your concerns as a writer? What do you think the teaching poet’s responsibility is in terms of equipping young people, and particularly young people of color, for survival in the face of suffering, violence, and disaster?

PR: It was never my intention to write about children, but in the last five years or so, they’ve been entering [my work]. Maybe it has to do with watching all my nieces and nephews grow. Some are still toddlers. Others are grown adults. In all, I think this book wants to talk to the future. You could build a time machine to do that or you could spend time listening and talking to the ones who are meant to outlive you—which is to say, our youth.

As for the public visibility of the brutality against youth of color, to me, that’s just news headlines. To me, the news is late. If you have lived in and around communities of color, you know that this has been going on a long time. You’ve been angry at the deck stacked against people of color. But if you’re smart, then you’ve also been paying attention—not just since 2011 or whenever folks in the general public decided they needed to get hip to it—to the truly sophisticated ways that young people have sung and danced and written their way into survival. You want to be a good citizen? Learn how to celebrate. Learn how to mourn. You learn that from your family and your friends. But also, you have to learn all the ways that different people praise, how varieties of people grieve. You have to become fluent in as many languages of joy and sadness as you can. And don’t just hear the song, feel it. I want so much to be connected to my sorrow because as a Filipino, as a man indoctrinated into American masculinity, I’ve been cut off from sorrow. And I want that sorrow to contain not just my private injuries; I want this sadness —maybe one day—to hold many, many, many kindred sorrows. I have this bit of faith in me that those sorrows get transformed when we begin to see them in relation to one another. And then we, in turn, are transformed. All kinds of laughter and singing and connection can happen out of that. All kinds of poems.

I’m not an activist or sociologist or psychologist, but I suspect poetry can help more than a few people of color by acknowledging their inner worlds, their vast and rich catalogs of imagery and dreams. I think poetry has a good shot at helping young people learn how one’s inner world is clarified by trying to map its proximity and distance to other inner worlds. I would love this for young people. I would love for us to figure out how to do this in a meaningful way.

LR: As you’ve described, music deeply undergirds your work, and of course, Brooklyn Antediluvian is no exception. In the opening poem of the collection, there’s a lovely few lines where you describe the serendipitous moment when two decks sync of their own accord, independent of the DJ’s intervention. As a former DJ and music producer, how does what you’ve learned from the craft of music-making and -mixing figure into your own process for drafting and revision? How do you know when the sound of a poem has finally “clicked” and come into the right alignment? If you could map a soundtrack to the time period in which you were writing Brooklyn Antediluvian, what would be on it?

PR: Music is really the center of my process. A lot of it is intuitive and some of it is—for lack of a better word—mysterious. I’m following the sound of a word or phrase, and during revision, I have an idea that a particular sound wants to come back. A lot of my process at every stage is substituting different words into a line based on a sound or series of sounds. What enters is often a more precise word or a word with associations I hadn’t expected or planned, a wilder word. Conceptually speaking, music is what connects us because it makes a pattern. But music is also the opportunity for surprise because that pattern can break and vary.

I love this soundtrack question. The first artist who comes to mind is John Coltrane, who would take a phrase and repeat it by turning it upside down, playing it backwards, distributing individual notes from the original phrase into the rest of his solo, etc. I listened to a lot of Coltrane while writing this book. I listened to Bach’s cello suites (I love Pablo Casals) and Goldberg Variations too, for many of the same reasons I listened and continue to listen to Coltrane. But I also just love the music. It moves me.

Who else? Rufus and Chaka Khan, Sly Stone, Donnie Hathaway, Sam Cooke—they’re always on regular rotation anyway. While I was making my last revisions and edits, I listened to a ton of Latin and Afro-Latin music like Los Van Van, Pupy y Los Que Son Son, Fania All Stars of course, Joe Bataan, Conjunto Clave y Guaguanco, Dafnis Prieto, Ray Barretto, so many. I’ve been thinking (and feeling) a lot about swing and 12/8 and all kinds of things around music, so I’m sure all of it touched something in the book at some point.

LR: This is your fourth book and also the fourth you’ve published with Persea Books. How did you and Persea find one another before the publication of your first collection, Uprock Headspin Scramble and Dive, and how would you say that your writing and your relationship to the work that accompanies the publishing and promotion process for a book have changed since then, if at all?

PR: I’ve known Gabe Fried, the poetry editor at Persea, since he published poems of mine in Columbia’s literary journal back in 1999 or so. I was one of the first poets he signed when he started the poetry series at Persea. And it’s kind of crazy and a real honor to be on a press with Nazim Hikmet and Paul Celan and then all my contemporaries too.

I think it’s pretty rare for a writer and a press editor to be together as long as we have. I mean, seventeen years? I still don’t know how Gabe figured it was a good idea to publish my first collection, when so few books on literary presses came out of a hip hop sensibility and none that I knew of, back then, explicitly came out of b-boy culture. I was mixing up all these traditions that hadn’t done a whole lot of hanging out together in contemporary poetry—deep imagism, DJ culture, confessionalism, modernist collage, immigrant narratives, Catholic prayer, the dozens. I got a poem in there that makes reference to quantum physics and Amadou Diallo. I’m sure most of the poetry reading public in 2003—you know, the Paris Review and the New Yorker people—were not nearly in the realm of thinking about those kinds of connections as material for contemporary poetry back then. Gabe, along with my publishers Michael and Karen Braziller, made space for that book. I’m really grateful.

People have called Uprock juvenile—like, to my face pretty much—but when I think back, it was a risk to try and write poems like that for an established literary audience. And it was a risk for Persea to publish the book. Look at what some of the biggest publishers and most popular collections are doing now, more than a decade and a half later—Hip hop references? Race? State violence? Eros? I think that’s what a good editor does—takes chances on poets taking chances.

In terms of promotion, I’ll be honest. I loved my teachers in grad school and learned an immense amount from them, but they weren’t the kinds of mentors who would open professional doors for me. (What doors were really available anyway, except niche presses with a political bent?) My approach has mostly stayed the same. Write and perform the best poems I can. Listen well. Connect to ordinary people in the most meaningful ways possible—both on the page and in person. If I’m to be ambitious, let the ambition be about the level of intimacy and discovery with everyday people. All the other stuff will happen on its own—or it won’t. Of course, great works of art get remembered. But great works of art also evanesce or vanish outright. I’m not interested in making monuments, even as I’m interested in something eternal. The depth and complexity of a human relationship is eternal. I’m trying to invest my energy in that.

LR: What’s next for you? What projects are you working on now?

PR: I’ve got so many things I’m excited about. I’m really enjoying the life of Brooklyn Antediluvian, first of all. I’m enjoying reading from it. Actually, I’m hoping to find the right venue and live audience that will let me perform the title poem all the way through, which takes about a half hour to forty-five minutes; I’ve yet to do that.

I’m probably about two-thirds (maybe more) of the way through an essay collection on poetry, music, sports, race, my family, and other themes; it’s called The Symbol and the Task. This past spring I finished an essay I’m proud of that will be in an anthology on passing edited by Lisa Page and Brando Skyhorse. So there’s a good bit of prose ahead of me, I think.

Also, Gabe and I have talked about doing a New and Selected Love Poems. I’ve got to get the structure down because I don’t think it’s going to be arranged like conventional selecteds, I’ll probably mix up the chronology. And, finished or unfinished, I’m probably going to include this long episodic love poem I’ve been working on for a decade. In addition to that, I’ve been writing new love poems, too.

To me, this isn’t just any old selected and it’s not just love poems. I mean, the way Asian American men are still portrayed in the twenty-first century—no ferocity, no complex inner life, no eros—it’s just ridiculous to me. All these flat portrayals, all these comfortable formulas—they are part of the rampant brutalizing machismo that seems to be making a comeback. We gotta face it. Putting this book together has been really rewarding, in that I’ve been trying as an artist to be part of this discussion for so many years. It feels like the right time. And the book is not far from being finished.

* * *

Patrick Rosal is the author of Brooklyn Antediluvian, his fourth book. His poems and essays have appeared widely in journals and anthologies. He has served on the faculty of Kundiman’s summer retreat for Asian American writers and is an associate professor in the MFA program at Rutgers University-Camden.