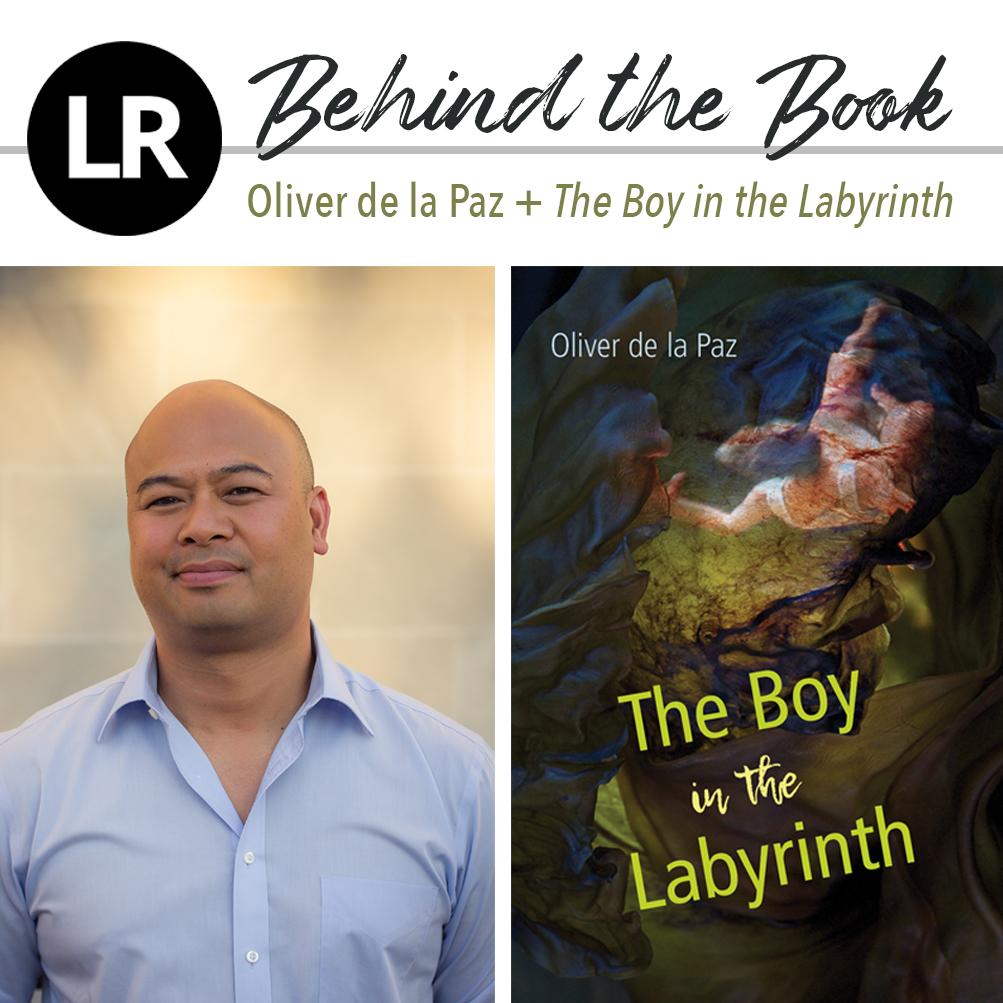

Happy first week of autumn! Today, we’re excited to debut a brand-new blog series. In “Behind the Book,” we’ll chat with authors of new or recent collections about craft, process, and the stories behind how their books came into being. It’s our privilege to start off the series by chatting with contributor and longtime friend of the magazine Oliver de la Paz. Read on to learn how he pursues the discipline of returning to the page amid the busyness of family and academic life and how he grapples with writing about deeply personal subject matter—as well as about the long spool of a journey that led him to the heart of his breathtaking new collection, The Boy in the Labyrinth (U of Akron Press, 2019).

* * *

LANTERN REVIEW: Can you tell us more about how the project for The Boy in the Labyrinth was born? Was there a specific generative moment, as in the encounter with Alicia Ostricker you recall in the Credo? How did the pieces of the story begin to make their way to you—and at what point did you realize that the boy in the labyrinth was your sons?

OLIVER DE LA PAZ: I had made a trip to read for the Slash Pine Festival in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, around 2007 or 2008. That was right around the same time my wife, Meredith, was pregnant with our first son. The poet David Welch had read a few poems, which really had resonated with me in terms of tone, so I tried my hand at a few prose poems that were operating at a similar tonal level. And I thought nothing of it. I kept writing these poems about a mysterious boy in a labyrinth. The writing got a little more frenetic as the magnitude of raising a neurodiverse child as someone who was neurotypical and completely uninformed about parenting started to sweep through my consciousness. But I didn’t connect the fact of the poems with the story of my sons until later, honestly. I continued with the strange little tone prose poems about this boy for almost ten years without looking up and realizing what I was doing. Once I realized their connection, I stopped writing them and started writing poems that ended up being the connective tissue—the questionnaires and the story problems started to trickle into the work about three years ago, and that was when I realized what I had in front of me. The poem “Credo” that opens the book was borne out of necessity. I realize that the book suffers a fatal flaw, and that is context. I had to acknowledge, in writing, my fumbling manner of writing around my anxieties and face them head on.

LR: You begin with apology (specifically, to your neurodiverse sons for writing about them)—something that, you inform the reader, is part of your writing ritual. What is the significance of apology in your writing process? While writing this book in particular, how did you weigh and wrestle with the implications and responsibilities of writing about your children?

OD: Well, I’m still quite uncomfortable about this book and that it’s out. Part of that discomfort is because I’m writing about my sons. At the time of the start of the work, they were really young and didn’t have a whole lot of say in what it was that I was doing. There was no correction from them in my wrestling with my understanding of neurodiversity. Now, my oldest kid’s almost a teenager, and he’s clearly delineated for me his boundaries. He’s read through the tricky parts, and he’s given me a nod, but further on down, I’m not sure how he’ll feel, and so we may have a very different conversation about this book. And so the apology is, in many ways, for the future. I acknowledge that this book is an artifact of a particular time that fixes my sons at a particular age with struggles that are/were particular to a specific moment in time, and in many ways we have all moved beyond that time.

LR: The impetus behind this book is so personal. Did you ever feel the need to give it space for a period of time when engaging with it felt too emotional? If so, what did those moments of space look like for you, and how were you able to keep bringing yourself back to the work each time?

OD: Oh, absolutely. I worked on other projects to get my mind off of this project. I published Post Subject: A Fable, and I worked on a sixth manuscript. The two projects outside of The Boy in the Labyrinth were much more observational, though what remained intact was the allegorical nature of the writing. I think that thread spreads throughout my work. But then I’d be reminded that I also needed to tend to the more personal work. I don’t know about how other writers work, but I’m usually juggling two or three manuscript ideas at once so that if my mind is fatigued by any given project, there’s always another work that needs my attention. Again, I had worked on the poems in The Boy in the Labyrinth for nearly ten years, so I took many breaks away from the book to get my mind right but also to accommodate being a dad and being a teacher.

LR: How did you find your way to the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur and the use of the Greek ode as a form by which to structure the movement of the book? What craft considerations informed your process while trying to shape the narrative within this Classical framework?

OD: The structure came later. Part of my responsibility in working on such a large singular work is to usher a reader through its girth. It’s extremely dense and seemingly repetitive, which is the nature of obsession and writing through accretion. By imagining the work as akin to a Greek ode, I was also thinking about how the structure of the Pindaric odes commemorated events and how there were predictable elements of ceremony and ritual. I take my kids to church, and there are always particular rituals that they understand (they especially know when mass is about to end). So the Classical structure helped me organize the large morass of writing that I had done, but I also wanted to help the reader through the journey.

LR: How, if at all, did your process of composing the narrative prose poems in this book differ from your process for writing into the other forms that surround and weave through them (e.g., medical questionnaires, “story problems,” etc.)?

OD: I usually alternate between writing in verse and writing in prose forms. As I had mentioned, I’m usually juggling several projects at once, and I had been writing Post Subject: A Fable concurrently with The Boy in the Labyrinth. Both of these manuscripts take their cues from allegory and fable, and I had always associated parable and allegory with very short, concise prose. I wanted to interrupt the fabulist tendencies by writing in a more clinical mode. And I wanted to interrogate the form of the standardized test or the medical questionnaire, but mostly, in my process, I truly and actually needed a break from the discursive mode of allegory. The first of the works to be written outside of the allegorical mode was the “Autism Spectrum Questionnaire: Speech and Language Delay.” And that opened my mind up to other possibilities of writing that were in dialogue with the allegorical stories. They were all written together as a chunk—I don’t write throughout the year. I wrote almost exclusively in the summer for a very short and dynamic amount of time. So, naturally, when I started down the path of writing out these questionnaires, more and more came about because of the intensity of my limited writing schedule.

LR: What were some of the joys and challenges of working on a project over such a long period of time? Do you have any advice for maintaining (or fostering) a sense of continuity among pieces written at very different points in time?

OD: Again, given my really limited amount of writing time due to parenting and all the other duties that are part of teaching in academia and being a spouse, I had to make some concessions with who I was as a writer, and so I developed a practice that grants me an immediate path when I take the task of writing up the following day. What you don’t see in The Boy in the Labyrinth are the cues that I left myself in syntax and structure that allowed me to continue the sequence. A number of them got cut in the final edits. I will say that Post Subject: A Fable shows many syntactic gestures that I used to help “warm up” my writing brain. I paint on big canvases. I almost always think of individual poems with respect to the poems adjacent to them—how a particular poem activates or negates the work surrounding it. I think in motif and pattern, and I love making bigger connections both in my own writing and in the work of writers whom I enjoy, either in individual poetry collections or a life’s work.

Of course the challenge of writing in such modes is almost always sustaining the work, and I suppose I enjoy the discipline of continuous project building. In the end, there’s something about working on a singular, sustained project that is akin to controlling one’s time.

My mother wakes up every day at around 4 AM, makes her coffee, reads, and then does her exercises. She has done this all my life. She is now in her late seventies, and she has Parkinson’s, but her ritual still persists. I admire her defiance, and in a way, writing in such an insistent, systematic, and sustained way is a kind of defiance for me. A way of making space for a ritual against the din of the world.

* * *

Oliver de la Paz is the author of five collections of poetry: Names Above Houses, Furious Lullaby, Requiem for the Orchard, Post Subject: A Fable, and The Boy in the Labyrinth. He also coedited A Face to Meet the Faces: An Anthology of Contemporary Persona Poetry. A founding member of Kundiman, Oliver serves as the cochair of the organization’s advisory board. He has received grants from the NYFA and the Artist Trust and has been awarded two Pushcart Prizes. His work has been published or is forthcoming in journals such as Poetry, American Poetry Review, Tin House, The Southern Review, and Poetry Northwest. He teaches at the College of the Holy Cross and in the Low-Residency MFA Program at PLU.