In celebration of APIA Heritage Month, we’ll be running a special Poetry in History series once a week in lieu of our Friday prompts. For each post in the series, we’ll highlight an important period in Asian American history and conclude with an idea that we hope will provoke you to respond. Today’s post centers around the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

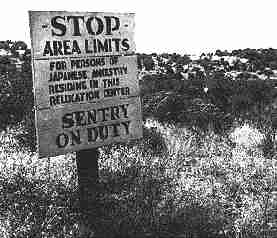

We’ve all seen the photographs: bleak desert landscapes, makeshift barracks, endless stretches of barbed wire fence. We’ve heard the euphemisms: “relocation,” “evacuation,” and “evacuees,” put into circulation by President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 and the infamous public notices that appeared shortly afterward, stapled to telephone poles and pasted in store front windows addressed “TO ALL PERSONS OF JAPANESE ANCESTRY.” For the Japanese American, Asian American — any American, really, regardless of “ANCESTRY” — what are we to make of this moment in our nation’s history, when approximately 110,000 men, women, and children were robbed of their rights, property, and due process of the law in the name of “national security”?

In an era of liberal personhood, when most — but certainly not all, recent legislation in Arizona being a case in point — citizens of the United States enjoy relative protection under the law, how are we to respond to the egregious moment in 1942 when crowds of Japanese immigrants and their American-born children were herded onto fairgrounds, relegated to horse stalls and racetracks, and “relocated” to barbed-wire compounds and hastily constructed prison barracks throughout the nation? And all this, in response to sentiment like that expressed by columnist Henry McLemore: “I am for the immediate removal of every Japanese on the West Coast to a point deep in the interior. I don’t mean a nice part of the interior either. Herd ’em up, pack ’em off and give ’em the inside room in the badlands… Personally, I hate the Japanese. And that goes for all of them.”

Violet Kazue de Cristoforo’s article “Pre-War Japanese American Haiku,” available on the Modern American Poetry website of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaigne, offers a glimpse into the literary life of the Japanese American community before and during World War II.:

The Delta Ginsha [a free-verse poetry club] was founded in 1918 by Neiji Qzawa… Its members met monthly and submitted their haiku to the master of the month, who was usually the host or hostess for the evening. They submitted for consideration as many poems as they desired. The poems were then read and discussed and a vote was taken to determine the best haiku… It was an evening anticipated by the members—grape growers, onion farmers, teachers, housewives, bankers, pharmacists, and others—who had assembled for an enlightening cultural and social event.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of the war, however, most — though not all — of these poetry clubs dissolved for fear of reprisal. Dozens of poetry collections were destroyed, along with entire libraries of Japanese literature: essentially an erasure of the community’s literary history. For more information on World War II era free-verse haiku by Japanese Americans, see de Cristoforo’s book May Sky: There is Always Tomorrow–An Anthology of Japanese American Concentration Camp Kaiko Haiku, published by Sun and Moon Press (1997) and the anthology Only What We Could Carry: The Japanese American Internment Experience (Heyday Books, 2000), edited by prominent Japanese American writer Lawson Fusao Inada.

* * *

In the spirit of the Delta Ginsha and other free-verse haiku (or kaiku) poetry clubs that emerged in the early 1900s and went on to flourish in the interment camps, write a haiku that captures, through image, sound, sensory detail, and/or meditation on the seasons/natural world, a state of mind or being that illuminates far more than what it suggests initially. Consider the following examples, written in “camp” and published in May Sky.

Autumn foliage

California has now become

a far country–Yajin Nakao

Frosty night

listening to rumbling train

we have come a long way–Senbinshi Takaoka

If you’d like to read more about the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, here are some additional resources:

Poetry

Drawing the Line and Legends from Camp: Poems, by Lawson Fusao Inada.

Camp Notes and Other Writings, by Mitsuye Yamada.

Fiction

No-No Boy, by John Okada.

Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories, by Hisaye Yamamoto.

Songs My Mother Taught Me: Stories, Plays and a Memoir, by Wakako Yamauchi, edited by Garrett Hongo.

Nonfiction / History

Remembering Heart Mountain: Essays on Japanese American Internment in Wyoming, edited by Mike Mackey.

Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz, by Sandra C. Taylor.

Inside an American Concentration Camp: Japanese American Resistance at Poston, Arizona, by Richard S. Nishimoto, edited by Lane Ryo Hirabayashi.

Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps, by Michi Nishiura Weglyn, with an Introduction by James Michener.

Legacy of Injustice: Exploring the Cross-Generational Impact of the Japanese American Internment, by Donna K. Nagata.

* * *

If you write about the internment experience this week, please post an excerpt of your attempts in the comments. Also, if you live within driving distance of Manzanar, Tule Lake, Minidoka, or Jerome, etc., consider visiting one of the former internment camps, many of which have continued to remain open to the public.

Dear Mia,

I just stumbled on your website. I am looking for the image you are using on this page (Lantern Review Blog- Asian American Poetry Unbound, Poetry in History: Japanese American Internment; 2010 MAY 15). It states a photo credit of: California State Library, description: shot looks like it was taken from the train view looking down at the crowds in the assembly center/or relocation centers through the barbed wire fence – The train is either leaving or arriving.

I want to use it in a film for Heart Mtn Center. If you have any information (ID number) that would help me order a digital file from the CA State Library – I would be most grateful. Zand Gee/Farallon Films

email: geefess@sbcglobal.net

Hi Zand,

Absolutely — the photo is taken from a Library of Congress exhibit called “Exhibition: Voices of Civil Rights” and the website can be found at:

http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/civilrights/cr-exhibit.html

Scroll down to the section on “The Relocation of Japanese Americans” and you’ll find all the information you need about the image (I’ll paste here as well for your convenience).

“Crowd behind barbed wire fence at the Santa Anita Assembly Center in California, wave to friends on train departing for various relocation centers located throughout the United States, 1942. Photograph by Julian F. Fowlkes. Copyprint. U.S. Signal Corps, Wartime Civil Control Administration, Prints and Photographs Division (3) Digital ID# cph 3b07599”

Please stay in touch — I’d be very interested to hear more about your film project!