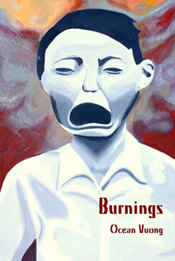

Burnings by Ocean Vuong | Sibling Rivalry Press 2011 | $12.00

Ocean Vuong’s first chapbook of poetry, Burnings, is a searing elegy to a deceased motherland that continues to smolder in the memories of those who left her in the wake of war. Although Vuong is a member of the 1.5 generation (the children and infants of Vietnamese refugees with scant memories or no memories of that armed conflict) his writing boldly confronts, grapples with and reflects themes of personal and political dissolution and regeneration.

Do not say our names as this flame grows

from the edge of the photo, the women’s smiles

peeling into grimaces, the boy spreading slowly

into black smudge, filaments of fire

dissolving into wind. No, do not say our names.

Let us burn quietly into the lives

we never were.

[from “Burnings”]

What comes forth in the title poem is the shock of tangible, catastrophic loss. It gives you the feeling of being gradually burned down to a nub, leaving behind only a trail of stoic grief, and in order to get on in life and persevere you must transcend it.

An apt Mark Doty epigram divides Burnings into two sections, but the transformative medium of fire is the theme that runs throughout the chapbook. As I read Vuong’s poems, I imagined each one warping and crinkling in my hands, heating up my fingers, as if someone had lit a match at the corner of the page. The slow burn of Vuong’s verse and his juxtaposing and melding of life and death give off sparks in the dark that illuminate truths which one never truly forgets.

The martyred, yet truly luminous, mother figure appears often in Vuong’s sorrowful, yet engaging, lyricism. Seemingly blessed with the role of carrying and bringing forth human life, the mother figure in the poem “My Mother Remembers Her Mother for Le Thi Lan (1941-2008)” is not weighed down with any Mother Earth sentimentality:

There are men who carry dreams

over mountains, the dead

on their backs.

But only our mothers

can walk with the weight

of a second beating heart.

When I read this stanza over and over, I started to notice the cycle of creation and destruction interwoven in the words. One could surmise that boys are born of women and they will eventually grow into men who are one day forced, or are willing, to kill the offspring of other women who could very well bear a resemblance to their own mothers. What could be worse than thinking that the “second beating heart” could grow into a murderer?

The father figure in Vuong’s poems is habitually absent, but not exactly, because he acts very much like a maligned shadow, ever-present, yet consciously skulking around on the periphery. In the poem “Song of My Mothers,” the focus is on the Vietnamese female subject and her travails during the war, but the incinerated husbands lurk in the negative spaces:

Of the wives who charged

into burning fields,

who knelt and scraped

someone else’s husband

into cracked jars of glass.

and as do the foreign fathers who, supposedly, leave behind illegitimate children in brothels, intermixing life and death:

Sing of the daughters

who surrendered their names

to the nights of Sai Gon,

whose bodies became bed frames

for men who touched breasts

as they would the top of skulls.

In the poem “The Touch”, which was published in the first issue of Lantern Review, the yearning for the absent father is especially prominent. This poem could be interpreted as two separate fantasies merging into one, as the mother mourns the absence of her husband and the boy mourns the absence of his father, while stepping into his shoes as he comforts his mother at night:

She softly exhaled as I pulled closer knowing

This was not right: a boy reaching out

And into the shell of a husband. …

Another major theme that Vuong plays on continuously throughout Burnings is song or the act of singing. When all seems lost, when one must leave the homeland without the comforts of home, a familiar tune, a folk song, is all one has that can recall fond memories or, unfortunately, remind one of what he has left behind and will eventually lose:

… Listen. Someone is trying

To croon that old song, but the voice cracks over words

Like Mother, Home. …

[from “Arrival by Fire”]

A song can also be an act of defiance and self-actualization in the face of social forces that seek the annihilation of a forbidden love or true identity:

As those fig leaves lay torn by our feet,

somewhere, someone was beginning to sing.

I had to touch my lips

to know that hymn

was mine.

[from “Revelation”]

Finally, possibly one of the most beautiful poems in this collection is “Gardening with the Son I Will Never Have.” It is a poem that deals with the inevitability of life and death and the natural state of existence. The poet seemingly splits into adult and child versions of himself in order to facilitate a conversation that has been inherent within father-and-son pairings for generations:

How do I explain

to the small boy beside me,

the difference between his skin

and the velvet shells of tulips?

On the surface, for the sake of scientific categorization, and cognitively speaking, humans and flowers are separate beings, although we both share the same air and ground on this planet. Essentially, though, we are very much the same. We are earthly organisms that will live and die; we both grow and then, over time, our bodies deteriorate until we can function no longer and, in the end, our molecular structures must return to the dirt.

That to press a finger into soil, we

are not too far away.

The title of the poem, “Gardening with the Son I Will Never Have,” very cleverly defines Vuong’s young life, which seems ripe with possibility but is highly attuned to his lived reality.

Ocean Vuong’s masterful poetry is something any literary enthusiast should experience. His poems share a worldly sadness that paradoxically recalls the joyful magic that can spring forth unexpectedly in life. Vuong’s words hold inside them a wisdom that speaks across and through generations of people who have suffered and then go on to persevere. Burnings is definitely for any reader who is looking to come in from out of the cold.

One thought on “Review: Ocean Vuong’s BURNINGS”