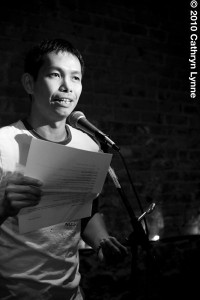

Jee Leong Koh is the author of three books of poems, including the recently published Seven Studies for a Self Portrait (Bench Press). His poetry has appeared in Best New Poets (University of Virginia Press) and Best Gay Poetry (A Midsummer’s Night Press), and in journals such as Cimarron Review and PN Review. Born and raised in Singapore, he lives in New York City, and blogs at Song of a Reformed Headhunter.

* * *

LR: Seven Studies for a Self Portrait is divided into seven chapters, with seven poems in each chapter, and forty-nine in the last. What is the significance of the number seven?

JLK: Seven days in a week. The practice of writing a poem a day is important to me. The days when I don’t write feel empty to me, incoherent, lost. A day, like a poem, is invaluable for itself and also for being a part of something larger, like a week or a life. I wrote my first book Payday Loans, a series of 30 sonnets, in the month before I graduated from Sarah Lawrence College with my MFA.

One of my favorite poets, Philip Larkin, asks in a poem, “What are days for?” He answers himself, as poets have the habit of doing, “Days are where we live.” A day is an on-going project. At the moment I am reading Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. She speaks of Nietzsche’s will to power as a project of self-transcendence. When Larkin considers transcendence, he says in his typically sardonic manner that the question brings the priest and the doctor running. Because I have lost my faith in organized religion and have yet to place my life in the hands of medical science, I am working out my daily transcendence in writing poetry.

I wrote Seven Studies for a Self Portrait in two years. As I wrote, the number seven acquired and transformed its Christian meanings—the days of Creation, the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Eshuneutics, who reviewed my book, puts it well, “This silent structuring … evokes a tradition running from the mediaeval period and sets a context for the spiritual enquiries within the book.” Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, from which my book got its epigraph, was an inspiration for the post-Christian enquiry.

As vital as the spiritual quest was for me, so was the musical composition that the number enabled. A sequence of seven poems has not only a beginning and an end, but also a well-defined middle. It also breaks up into two unequal parts—four and three—half of the sonnet’s proportions. The first six sequences in fact culminate in two sonnet sequences, one English, the other Italian. Breaking through and re-working that framework is the final set of 49 ghazals, each made up of seven couplets about love. The ghazals raise, in my imagination, a 7 x 7 x 7 cube. In planning this structure, I was thinking very much of Herman Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game, in particular, the last game that the Magister Ludi builds from the floor plan of a Japanese house.

LR: The poems in Seven Studies for a Self Portrait are chiefly concerned with different ways of viewing the multiple facets of the self, simulacratically, if you will. What was the motivation behind this preoccupation? Were you affected by the new social media?

JLK: To speak biographically, my life is broken up in various ways. I moved from Singapore to New York in 2003, at the age of 33. I left behind family, friends and career in order to build a new life for myself. This new life does not only include the poetic vocation, but also a new identity as a gay man. I wrote about the experience of coming out as gay and expatriate in my second book Equal to the Earth. But Singapore will not go away. I need distance from it to write about it, but writing does not close the distance between me and the bookish child I was, the Bible-thumping adolescent, or the ruler-wielding teacher. Living in the States has deepened my perceptions about race, ethnicity, gender and class. These perceptions have sharpened my understanding of society, but turned inwards, they cut up the self into multiple fragments. Again and again I hear the same debates about whether one should identify as a gay poet, a woman poet, an Asian American poet or what have you. I find it near impossible to give an answer in prose. I prefer to let my poetry speak. I find in writing what Frost calls “a momentary stay against confusion.” I would add, however, that being gay is vital to my poetry, in ways that being Chinese and Singaporean are not. It is my motive force. It orders my creative agenda.

I consider myself a lyric poet living in an anti-lyric age. The illusions of the lyric “I” have been well catalogued: the simulation of psychic wholeness, the privileging of atemporality, the masking of social injustice, the marginalization of the Other. The new social media reinforce the fragmentation of the self. And yet I think the lyric answers to some very deep human need for complex music made by the human voice. By looking at the self in various ways, I try in Seven Studies to rework the lyric for our highly self-conscious times.

I look at the self through various lenses in the book. The title sequence is written after master self-portraits—Dürer, Rembrandt, van Gogh, Schiele, Kahlo, Warhol and Yasumasa Morimura. In contrast, the second sequence “Profiles” sketches the self sideways. “I Am My Names” is a series of riddles. “What We Call Vegetables” describes the organic basis of identity. I “translate” an unknown Mexican poet in one sequence, and speak as Ted Haggard, the Evangelical pastor accused of paying for gay sex, in another. The fragmentation of the self follows the example of Roland Barthes in the final ghazals, where I beg to be reconstituted by a lover-reader.

LR: Born in Singapore, educated in England, and living in America, some might call you a “gay transnational Asian poet.” That’s a lot of labels! Have you found such multiplicity freeing or constricting? How has your transnationalism affected your poetic career? Has it opened doors, allowing you to maintain inroads in England and Singapore as well as America?

JLK: If “transnational” means beyond the nation-state, I am all for it. On a lecture tour of the United States, Rabindranath Tagore told his American audience, “The idea of the Nation is one of the most powerful anaesthetics that man has invented.” The writer of Gitanjali, beloved in his own country, was critical of the blinkers of nationalism. I like to think that nothing human is alien to me. That I could potentially inherit everything human.

Certainly, moving to New York City has given me access to writing groups, editors and curators whom I could not possibly reach, or even know, from Singapore. Besides New York, I have read in Boston, Salem and New Orleans, and taken up writing residencies at Marilyn Nelson’s Soul Mountain Retreat and the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center in Nebraska City. I have also attended and benefited from the Kundiman writing retreat. The infrastructure for supporting writers here is incredibly extensive and well established compared to that in Singapore, and probably many other countries. American writers are very lucky.

I try to keep up with the Singapore literary scene, which is small but active. I return home regularly to participate in the Pride month reading. Last summer a local bookstore organized a book launch for Seven Studies. The quality of poetry coming out of Singapore now is under-recognized in the States. Cyril Wong, Alvin Pang, Aaron Lee, Hsien Min Toh, Alfian Sa’at, Li Sui Gwee, and Yi-sheng Ng all deserve to be better known. At the most recent conference of the Association of Asian American Studies, there was no academic paper on Singapore literature, though there was one on Singapore film. Singapore literature can be usefully studied as part of the “transnational” approach.

I am certainly not the only Singaporean writer living in New York City. Hwee Hwee Tan, who published her first work of fiction Foreign Bodies at the age of 22, lives here too. Wena Poon, whose first book Lions in Winter was longlisted for the Frank O’Connor Prize (Ireland) and whose poetry was shortlisted for the Bridport Prize (UK), divides her time between New York City and Austin. So residency in the States is no barrier to recognition in the UK and Ireland, such is the fluidity of transatlantic networks.

Other Singaporean writers have taken other routes. Poet Kim Cheng Boey migrated to Australia and now teaches at the University of Newcastle. Yew Leong Lee, who edits the exciting new international journal Asymptote, has just moved to Taiwan. The last example is perhaps indicative of a growing trend, that of journals and writers developing an international focus. We want to hear not just news but voices from all over a world growing rapidly smaller and more connected. Boey’s journal Mascara started out with a focus on Asian, Australian and Indigenous writers, but has since added an international section.

LR: You have now self-published three books and mastered the art of promotion. How has that process changed from book to book? How did you carve out an audience for yourself as a self-publisher? How did you stake your claim to critical legitimacy?

JLK: My first book Payday Loans was actually published by a small press in Hoboken, New Jersey. Working with Roxanne Hoffman the publisher gave me some idea of the workings of an independent press. I decided to self-publish my next book Equal to the Earth, and so set up my own imprint, Bench Press, for that purpose. I published Equal with Lulu print-on-demand but changed to Amazon’s CreateSpace print-on-demand for Seven Studies in order to sell my book on Amazon Marketplace. I really enjoy having total control over the publication of my books, working with a professional book designer to decide on the cover, layout and font. I threw an on-line book party for Equal at which I read aloud from the book and answered questions “live” on the book blog. Seven Studies was launched early this year at two house parties and a reading at Cornelia Street Café in NYC.

To build an audience for my books, I keep an active literary blog called Song of a Reformed Headhunter and a steady presence on Goodreads, Facebook, and Twitter. I also read and sell my books at the annual Rainbow Book Fair and, this year, at the Brooklyn Book Festival. I am a regular at the Son of a Pony reading at Cornelia Street Café, and people hear me or hear of me that way. My sales target is very modest: I aim to recover my publishing cost so that I can self-publish my next book. It took me some time to wear the hats of poet and publisher comfortably, but the satisfactions of working for oneself are rewarding.

In the brave new world of on-line publishing, the sources of critical legitimacy are more widely dispersed. On-line journals and groups are multiplying, and they gather around them a community of contributors and readers. I send my books to editors who have accepted my poems for publication. The relationship is reciprocal: they support my work and my work, in turn, supports theirs. I now have three reviewers who follow my work from book to book.

I also submit my books to the Lambda Literary Awards. Though Equal did not win last year, I was asked to join the judging panel for this year’s gay male poetry prize. It is a pity, I think, that the Asian American Literary Awards do not consider self-published entries. As my judging experience with Lambda can attest, it takes next to no time to separate a vanity press product from a serious literary production. I hope the Asian American Writers’ Workshop will review this rule, so as to keep in step with the changing times. I predict more and more serious writers will turn to self-publishing.

LR: What individuals (or entities) most influenced your poetic career and what were their best pieces of advice?

JLK: I did not think a Singaporean poet could both write well and write on matters close to my heart until I chanced upon Kim Cheng Boey’s Days of No Name in a bookshop. The book travels from [the] Iowa International Writing Program to San Francisco to Germany, while rejoicing in the painful pleasures of friendship, love and art. The other Singaporean poet whose work I love and measure myself against is Cyril Wong. His poetry is one of deep interiority. Unlike many of us, he has chosen to stay at home, in Singapore, and is producing an extraordinary body of work.

Stephen Dobyns at Sarah Lawrence College was very generous with his time and attention. I have internalized his call for clarity in intention and communication. His Best Words, Best Order is still one of the best primers around on writing poetry. John Stahle, who passed away last year, encouraged me to take the leap into self-publication. He designed Equal to the Earth and the Bench Press logo. Andrew Howdle, who lives in Leeds, England, has proven the worth of a virtual friendship many times over. I rely on his critical acumen.

Michael Schmidt has been publishing my work regularly in the British journal PN Review. He has also included me in the forthcoming Carcanet anthology, New Poetries V. A less obvious way in which he has influenced my career is his editorship of Eleven British Poets, the school text that introduced me to Philip Larkin.

Best advice? That must come from Poetry Free-for-all, an on-line poetry workshop to which I have belonged for nine years. I have learned so much from the international community there. One of the workshop moderators has condensed her wisdom into what she calls Scavella’s Mantra. It goes, “I am not as good as I think I am.” If that is not Asian, I don’t know what is.

Thank you for this interview.

Such an interesting journey beyond country and social barriers, I appreciate the courage and tenacity of this writer.

The ghazals are lovely.

I live in a small hole in the ground in Australia (watch out for the funnelwebs!) and hadn’t got the memo that we are living in an anti-lyric age. So much the worse for the age, I think.

I appreciate the recommendations for other Singaporean poets. I know Cyril Wong, of course, but many of the others are new to me.

Hi Corinne,

Thanks for reading the interview. You are generous in your evaluation. The journey should feel harder, but actually it felt perfectly natural.

Jee

Hi Rachael,

Consider the memo served. Now what will you do with it?

Do you know the Australia-Singapore poetry anthology titled “Over There”? The poets I mention can be found there also.

http://www.ethosbooks.com.sg/store/mli_viewItem.asp?idProduct=206

Thanks for reading the interview. I’m glad you like the ghazals.

Jee

Jee, I didn’t know that anthology, but it sounds right up my alley. And it there are two copies available in the University of Queensland library, so I’m in luck. Thank you.

*”there are”, not “it there are”. Drat my dratted typos. Anyhow, I appreciate both memos.

Two copies, Rachael? Now you can read with both hands.