As we announced last week, we’re back and more excited than ever to embark on a new journey with Lantern Review. It’s been a fruitful, restorative two years since we published our last issue, and as we’ve begun to ask ourselves what’s next, we’ve found ourselves reflecting on the lessons we’ve learned by going on hiatus.

Here are a few things we’ve discovered from taking our much-needed rest.

- Self-care is important. Nobody can do everything. There are seasons when it is necessary to attend to the non-art-related things in our lives—to family, to one’s health, to relationships, to the keeping of a roof over one’s head. These are the things that enable us to create making art. And it’s imperative not to neglect them if we are to live healthy, fulfilled, and sustainable lives both on and off the page.

- Keeping a notebook is a poet’s lifeline. It’s a record of the vital, ongoing dialogue with oneself, one’s art, one’s reading. Observations, notes, drafts of book reviews, quotations—when kept in a notebook, they become a record of the poetic sensibility in motion.

- Poetry can create family, but sustaining that family requires work. When we started LR in 2009, we were still MFA students, not too long out of college, and, like most young poets of color, hungering after a community to call our own. Over the years, our work on LR has provided us with a rare gift, in that it has made our chosen literary family uniquely accessible to us. So when we made a conscious choice to step back from the magazine, we had to find other ways to engage. What we learned in the months that followed is that often, community is one what makes of it. Sometimes it finds you on its own, but for the most part, one must seek it out, carving it out of the rock if necessary, to survive. How does one do this? By reading more books by poets of color. By writing to those poets. By bringing them into your spaces. By teaching their work in your classroom. Poetry knits artists together, but like any family, it takes effort to foster growth and belonging.

- Poetry and parenthood don’t have to be antithetical. Thoughtful, provocative resources on the relationship between these two pursuits exist, like The Grand Permission: New Writings on Poetics and Motherhood. A toddler can be a wonderful collaborator, especially when taken on a poetry scavenger hunt, where you rely on intuition and whimsy to shoot photos of any- and everything that captures your attention. Toddlers are gifted at the art of gathering dissociated images; of being the thing—the mind, the eye—that holds it all together; of allowing the poem to emerge on its own terms. Also: you have to be selfish. You have to steal time. You have to make it happen. Which leads us to number five.

- Writing is legitimate work, and it deserves to be prioritized. Especially when you have a day job, it can be easy to let your creative life slip into obsolescence. It’s tempting not to think of writing as Work (with a capital “W”) when it’s not the primary activity that’s putting food on the table. But for the vocational writer, the labor that goes into creating art and promoting one’s craft cannot be relegated to the status of a hobby or a side gig. Sometimes, keeping the literary life going means classifying writing-related tasks under the “work” column of the to-do list, cancelling social plans, neglecting the housework, and carving out whole Saturdays to attend to a draft or meet a contest deadline. Because writing is Work, and even if we don’t always succeed at keeping it a top priority, if we don’t at least attempt to treat it as such, we delegitimize ourselves and the value of our artistic vocation.

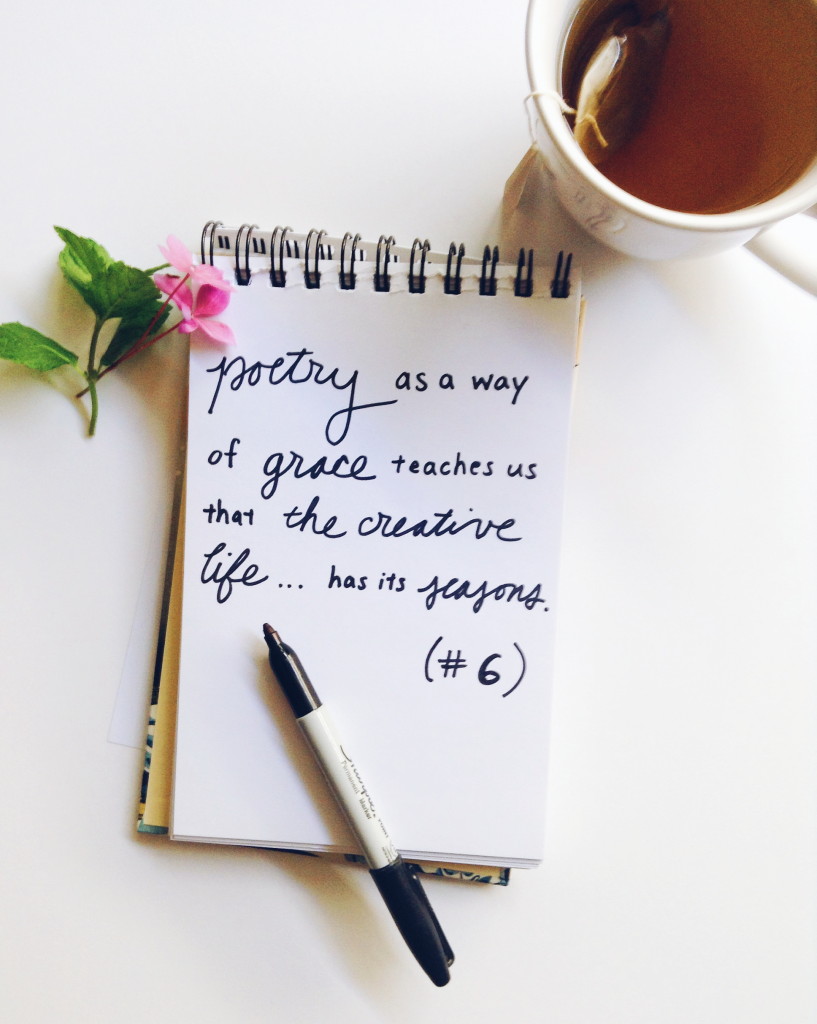

- Poetry as a way of grace teaches us that the creative life, like any life, has its seasons. Not all seasons result in tremendous bursts of productivity. Not all seasons generate fruit. Yet there remains a steady, living pulse to the poet’s way of life: pedagogy, critical engagement, the quiet cultivation of community and creative thought, the necessary work of professionalization. While we don’t always exist in these spaces simultaneously, they continue to exist for us, so we move in and through them with grace, filled with the certainty that there is a time for everything.

Have you ever taken an extended period of time away from your work? What did you learn from the experience? Tell us in the comments below, or share your insights with us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram by tagging us: @LanternReview. We’d love to hear your thoughts!

I would love to hear more about #2, keeping a notebook. I feel like what I write in longhand gets lost to me — it’s hard to read, difficult to search, time consuming to organize or reuse. Is there value in thinking on the page, even if you never re-read it? Or have you found ways to make it easier to transfer insights from your notebook into your more formal writing?

Keeping a notebook is a practice I began after hearing Sandra Lim’s talk, “On Intuition and Keeping a Notebook,” at the 2015 Kundiman Retreat. In her talk, she made the point that committing quotations, notes, etc. to the pages of a notebook is a way of trusting our deepest creative impulses, and how rereading one’s notes, later on, is a way to uncover the mind at work.

I’ve found that when I begin in the notebook, my quality of thought is more sustained, and my language more finely attuned. This may have something to do with paper and pencil being a space away from the computer screen—to me, a kind of frictionless field where words slide far too easily into sentences and paragraphs. Working on paper, I’m able to keep my ideas in the body (the hand, the mind, the heart), before technology makes of the work a sleek, mediated thing.

Later on, typing notes into a first draft becomes a form of revision, at which point I attend to syntax and structure but don’t have to worry about the ideas themselves—that work has been accomplished in the notebook.

There’s also something powerful about sitting down in front of a notebook, in that it signals to the mind and body that it’s time to enter one’s creative practice. I don’t get the same feeling from opening my laptop; on the contrary, that feeling is more like an itch that needs to be scratched: must check email, must manage logistics, must… For me, those impulses spell death to the dreamy, elusive corner of the brain I rely so completely upon for my writing.

To speak the issue of organization, it’s surprising how possible it is to find a certain quotation or set of notes—assuming, of course, that one’s notebook entries are titled and more or less chronological. Much like backtracking a train of thought, finding material in the notebook becomes a matter of remembering what you were thinking, or reading, before you thought, or read, something else. It’s a beautifully analog way of working, somewhat akin to browsing the books on a library shelf to find a specific title. You may not know the precise location of the volume, but the books are indexed sequentially, and who knows, you may (re)discover something interesting along the way.

A few other practical notes: Post-It notes, highlighters, dog-ears, and of course, the dogged (but invaluable!) copying of old notes onto a fresh page, especially if they hold the promise of a new day’s work. Hope this helps!