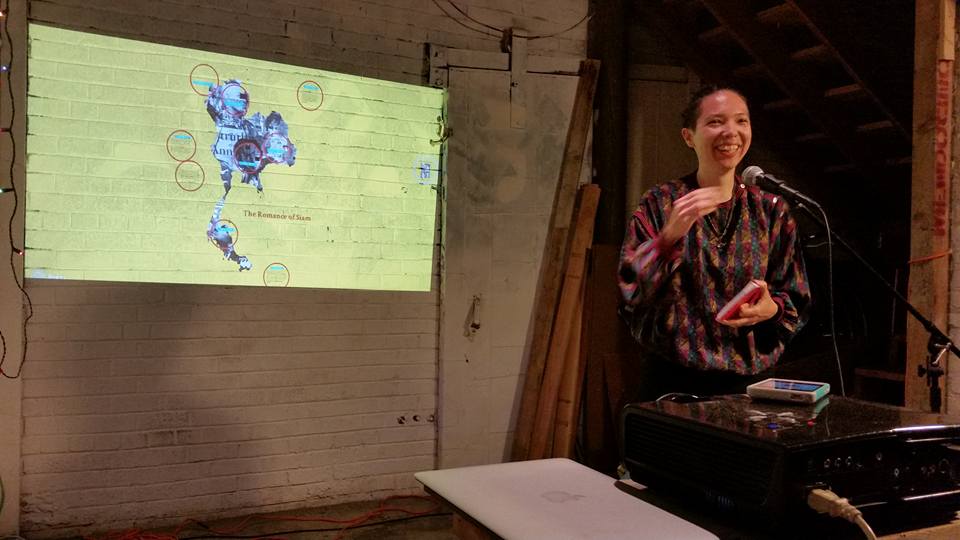

This month, we had the pleasure of talking with writer, dancer, and designer Jai Arun Ravine, who recently published The Romance of Siam: A Pocket Guide (Timeless, Infinite Light, 2016). Join us as Jai shares about the wormholes and winding side streets that led to the creation of their remarkable new book, which takes the pervasive specter of Orientalism in Western tourist writing head on. Read more of Jai’s book reviews here on the Lantern Review Blog.

* * *

LANTERN REVIEW: The Romance of Siam is so many things: travel guide, satire, cultural artifact, poetry, critical theory. In more ways than one, it says everything I’ve ever wanted to say about the ways the Western imagination constructs “Thailand” for itself—and, as you say, how Thai tourism perpetuates this fantasy for its own profit. So thank you for this vital, truth-telling work! The funny thing is, though, that in telling this truth, you tell very little actual truth—most of the pieces are fabricated, parodic, and relentlessly satirical. Tone is a notoriously difficult thing to manage in satire. How did you manage to keep it light, and yet, not pull your punches when it counted? Was it ever hard to keep playing the part, so to speak?

JAI ARUN RAVINE: In my research, I was constantly struck by the absurdity of everything in my path. I stumbled upon uncanny parallel traces, and hilarity abounded as soon as these seemingly disparate elements began to collide. Because I took myself, as a physical presence, “out” of the work for the most part, I began to choreograph these landscapes where actors and characters became my pawns. Something about having this kind of power over the board helped me stay “light,” I think. It allowed for my chess pieces to perform “the absurd” for me, and every time I moved them, they would inadvertently expose the stains of Orientalism that lay underneath it all.

LR: Beginning with the opening “Hints to Walkers” and continuing through the rest of the collection, your book is also profoundly intertextual, a ferocious, chimeric beast that begs, borrows, and steals voices from an impossibly wide range of cultural artifacts: screenplays, song lyrics, travel guides, promotional materials from the Tourism of Authority of Thailand, newspaper articles, early 20th-century novels, etc. How did you discover the sheer scope of the book? Did the subjects emerge as you proceeded through the project, or did you already know that there was a particular “canon” of relevant films, songs, and historical figures that you wanted to address?

JAR: When I began researching and writing for the book, I had a Fodor’s map of Bangkok marked with sticky notes for a few people, artifacts, and conceptual frameworks that I knew I wanted to explore further. But so many things emerged as I began to dig, and all the side streets began to wind and run into other side streets. I fell down a wormhole of “white elephants” and looked up everything in the library that had “Siam” or “Siamese” in the title. The song “One Night in Bangkok” led to The Oriental Hotel led to W. Somerset Maugham, in the same way that Anthony Bourdain led to Jerry Hopkins, and Jim Thompson led to Pat Noone. At a certain point, I had to make myself stop, because I realized there really was no end to the Orientalist and tourist archive; it constantly replicates itself. The final scope of the book arranges itself around theme and sequence, as well as destination and landscape.

LR: I’m fascinated by the ways in which you, as the author, exist as a felt present throughout the book, primarily via the “Information” and “Did You Know?” notes at the bottom of each page, where you comment, offer factoids and footnotes, and express interest in various critical features of the project. I was also struck by the moments when “you” enter the poems: you watch your mom talking to Tiger Woods’ mom; you play Anna in Jim Thompson’s low-budget film, The Silk King and I. What did it mean to you to introduce your own subjectivity—mediated, at times, by complex layers of form, fictionalized encounters, and performed identities—into the text? Was this always the plan?

JAR: In contrast to my first book, แล้ว and then entwine, where the writing came from a very personal need to define my relationship to ancestral histories and inherited silences, it was incredibly freeing (and a relief!) to take my ego out of the work. I imagined landscapes in which characters and actors from movies and plays could mash up and interact with each other. I could move through these icons as a kind of ghosted, energetic, electrical presence, and perhaps even hint at that nostalgic, “authentic” Thai essence that exists now as a work of fiction or as fusion cuisine.

Of course I couldn’t take myself out of the writing entirely, though, and especially in “White Love” and “Backpackers,” I make my anger toward white supremacy clearly known. But I think it was an important challenge for me to write a work in which the balance weighed more heavily on the other side of the scale. I did get completely caught up in directing my own theater, however, and at a certain point, it became too confusing for the reader—too many references, too crowded, too inaccessible. At that point in the draft manuscript, I circled back into the work, and with the guidance of writer and friend Marissa Perel, I realized that the moments when I inserted myself back into the text (when I stand side-by-side with Yul Brynner or Anthony Bourdain, for instance) were even more powerful than providing an anger-driven commentary on Orientalism’s devastating wake, or choreographing an intricate puppet show. I made a conscious choice in “The Silk King and I” to cut and paste “myself” into the scene, which I think made it stronger.

LR: You appear to speak most transparently in the opening “Hints to Walkers,” where you preface your project with the comment, “As a mixed race person of Thai and White descent, my attempts to connect with Thailand as ‘place’ and ‘cultural identity’ are colonized by tourism and White desire. […] This projects attempts decolonization in the face of such an erasure.” How did you make the decision to include this statement, along with the other prefatory remarks in “Hints to Walkers” at the opening of the book?

JAR: I have always found context extremely helpful. When an artist provides context for viewing their work, it gives the viewer a framework and a way into the experience. A lot of times, I read the work of a poet or see a choreographer’s dance performance, and if I’m not already familiar with the project, I’m distracted by the burning desire to know: What are the major concepts you are grappling with in this work? What is your relationship to the subject? How do you hope this object or performance will function in the world? I felt that stating these kinds of things at the beginning of my book (and during it) was crucial to its reception.I also outline some version of this before every reading I give. “Hints to Walkers” functions as a trail map, which lets people know what to expect on the journey. I see the “Information” and “Did You Know?” sections as other important trail markers that offer the reader both context and guidance.

LR: The Romance of Siam is, in so many ways, an unprecedented work of poetry, cultural resistance, and history. At the same time, I’m aware that even the most unprecedented work, no matter how wildly it reinvents genre, has its precedents. Who were the writers and thinkers who broke ground for you? What did you read, and to whom did you look for inspiration in the writing of this book?

JAR: I generated most of the initial material for The Romance of Siam during a residency at Djerassi in 2011, and one of the books I took with me was Jo Ann Wasserman’s The Escape. I read this book during Akilah Oliver’s course “Eros in Loss in Poetic Construction” at Naropa University in 2005. While I had never written much in classical forms, when writing The Romance of Siam, I remembered Wasserman’s book and the way she used the form of the sestina to work through her grief around her mother’s death. The sestina felt incredibly obsessive, but also somehow incomplete. The thing that one was grasping for could never be reached; it was a culmination without release. That feature of Wasserman’s work led me to writing a bunch of my own sestinas. Once I started, I couldn’t stop; the form just seemed to fit perfectly with my material (the Orientalist/tourist fantasy) and my relationship to it.

Even though I began reading the book after much of the material had already been generated, I am also indebted to Edward Said’s Orientalism, because he helped me identify a larger historical context for the project.

LR: There’s a fabulous moment at the end of The Romance of Siam when Jim Thompson’s character says that he wants to “purchase all the novels White man has written on Thailand and found a rare books annex” in Bangkok’s legendary Oriental Hotel—which I suspect exists, if perhaps only in spirit, as The Romance of Siam. This venture is described as a kind of “theatre within which [Thompson] has engaged much of his strange expertise and cultural knowledge,” a notion I find fascinating, given the particular prominence of theatre and performativity in your book. I was wondering if you could speak to the role of performance in your own life as an artist—or even as an individual, especially because I know you’re just as much a performance artist as you are a writer.

JAR: Performance is such a strong concept in The Romance of Siam because Orientalism itself is truly a performance that has been culled and animated from texts since the 1800s. Most of the West’s engagement with the Orient during the 1900s was via movies, film, and theater plays, and the stage is where its ideas and representations of Orientals (played by white actors in yellowface) are performed, solidified, and made legend. The way Yul Brynner performed the King of Siam, and royal Thai masculinity is forever burned on the collective psyche of contemporary culture. Theater is also a space where fact and fiction become blurred, a blurring I found again and again in Orientalist writings and tourist texts; Thailand was always more of a work of fiction, more like something from a book, than a real place, which is, in fact, where Orientalism’s true power lies.

In relation to my artistic practice, I trained in ballet from a young age and modern dance since college, and as a writer, I have always been drawn to the making of work that bridges text and body, which has led me to spoken word, video, and performance art. So creating a stage where I try to perform as Yul Brynner or Anthony Bourdain or Jim Thompson in this book sort of unmasks the constructions of race, gender, and the Orient and the Occident that I find so necessary.

LR: I have to ask, has there been much of a response to The Romance of Siam from Thai readers? Do you have any plans to work on a translation of the book? As many of us know, Thailand—like many other countries—fiercely policies foreign portrayals of its nation and subjects, and many of the films mentioned in your book (The Beach, The King and I, etc.) have been banned by its government. How do you think a Thai audience would receive The Romance of Siam, a depiction of the depictions deemed unfit for Thai consumption?

JAR: Ever since I created my short film Tom / Trans / Thai in Thailand and screened it at the Bangkok Arts and Culture Centre, Payap University, and the Alliance Française in Chiang Mai, I’ve come to understand that my work arises from its own specific context, which I very much define as of and related to the American QTPOC (queer and trans people of color) experience. The reception to my film in Thailand was not as meaningful for me as it was when I screened the project for QTPOC audiences in the States. So I suppose I’m feeling hesitant as to whether the book has relevance or solvency for Thai audiences. However, I have received some responses from queer Thai American friends, who I think can understand feeling both “inside” and “outside” with regards to Thai identity, being absurdly “mashed” with regards to race and representation, and being a tourist to oneself.

LR: Finally, what are you working on now?

JAR: I’m collaborating with writer Coda Wei on an experimental drama of text, comics and .gifs called Ambient Asian Space. We’ve been writing together since September 2015 and have recently started to release selected episodes here. I’m also working with choreographer iele paloumpis on a new dance work as part of the Oceanic End project, which we’ll be performing at a Draftwork showing at Danspace in New York City on December 10.

* * *

Jai Arun Ravine is writer, dancer, and graphic designer. As a mixed race, mixed gender and mixed genre artist, their work arises from the simultaneity of text and body and takes the form of video, performance, comics, and handmade books. The Romance of Siam is their second book. For more information, visit their website: jaiarunravine.com