A new school year is upon us, and if you’ve been following us for a while, you’ll know that we’re passionate about diverse books in the classroom. Anthologies are wonderful resources for teachers hoping to integrate a range of poetic voices into a curriculum, and luckily, 2019 has been especially bountiful in terms of new poetry anthologies and edited collections that feature diverse voices. Read on for three such titles that have caught our eye this year—and that we think would make fantastic additions to any classroom in the 2019–2020 academic year.

* * *

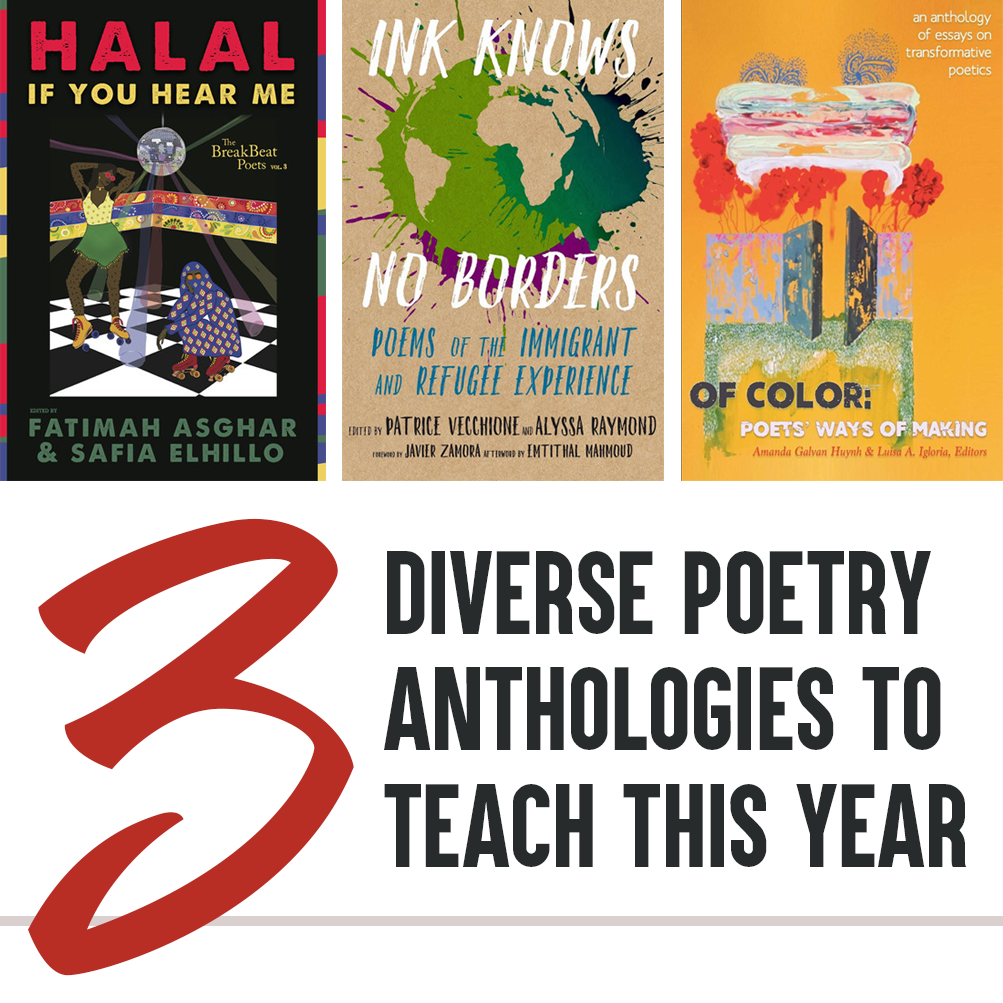

Halal If You Hear Me

(Haymarket Books, 2019)

Edited by Fatimah Asghar and Safia Elhillo

In assembling Halal If You Hear Me, editors Safia Elhillo and Fatimah Asghar set out to create a space that celebrates the diversity of the Muslim community. In her introduction, Elhillo writes of growing up afraid of “performing my identity incorrectly.” Asghar, too, writes of her own longing for acceptance. In contrast to shame and alienation, the editors have envisioned Halal If You Hear Me as a space of solidarity and freedom—a testament to the notion that, in Elhillo’s words, “there are as many ways to be Muslim as there are Muslims.” It’s safe to say that the editors have roundly succeeded: from Kazim Ali to Warsan Shire, the broad variety of poetic styles and backgrounds represented in Halal If You Year Me span a truly impressive range, singing and grooving across genres and generations. Halal If You Hear Me would make a fantastic choice for a high-school or community teaching setting, where its broad accessibility would make it an inviting point of entry into poetry. College-level and graduate courses, too, would benefit from the inclusion of this vibrant volume in their syllabuses.

* * *

Ink Knows No Borders: Poems of the Immigrant and Refugee Experience

(Triangle Square, 2019)

Edited by Patrice Vecchione and Alyssa Raymond

In a time where the notions of borders, migration, and citizenship are under constant scrutiny, Ink Knows No Borders seeks to highlight and celebrate the diversity that immigrant and refugee voices bring to the table. Write editors Patrice Vecchione and Alyssa Raymond in their introduction, “These lived stories, fire-bright and coal-hot acts of truth telling, are the poet’s birthright—and a human right. [ . . . ] Not only does ink know no borders; neither does the heart.” Indeed, this anthology sings with colorful narratives that bear witness. Featuring more than sixty poems that engage an enormous range of communities and experiences, the volume combines beloved favorites like Li-Young Lee’s “Hymn to Childhood” with more recent works like Aimee Nezhukhumatathil’s “On Listening to Your Teacher Take Attendance” and features a star-studded list of contributors that includes many of my [Iris’s] own favorite poets to teach—Joseph O. Legaspi, Franny Choi, Ocean Vuong, Alberto Ríos, Juan Felipe Hererra, Ada Limón, Bao Phi, and more. Ink Knows No Borders would be a wonderful text to teach in any high school or community setting or as an addition to any undergrad- or graduate-level reading list, while individual poems from the volume could also shine in the middle-grade classroom. To get you started, Penguin Random House, which distributes the book, has even helpfully provided a teacher’s guide to aid with introducing selected poems from the book to young readers.

* * *

Of Color: Poets’ Ways of Making

(The Operating System, 2019)

Edited by Amanda Galvan Huynh and Luisa A. Igloria

Born out of a student-teacher collaboration, this landmark volume thoughtfully collects together craft essays by poets of color—including numerous APA voices such as Ching-In Chen, Sasha Pimental, Ocean Vuong, and Craig Santos Perez. In keeping with the “windows and mirrors” principle, which proposes that students need to read texts that both offer glimpses into others’ experiences and reflect their own, Of Color tackles the need for diversity among not just primary works, but also among secondary writings on poetics, theory, and craft. In her introduction, coeditor Luisa A. Igloria recalls how the project came into being after a meeting when Amanda Galvan Huynh (who was then her student) confessed her frustration that “there was nothing in [her craft and theory courses’] syllabi or course reading lists that reflected who she was back to herself” (19). Indeed, the resultant volume speaks to a desire to carve out and create not just a resource—but a community. Writes Huynh in her own introduction, “To BIPOC writers: I hope you find what you need to hear in these pages, the support, the love, the struggle, and the reassurance that you are not alone in this poetic artistry” (16). A beautiful testament to the strength and importance of community, Of Color would be a strong addition to any undergraduate or graduate creative writing syllabus.

* * *

What books that you encountered in school helped open your world to diverse voices? If you’re an educator, what texts have you loved for including racially diverse perspectives in your curriculum? Share your recommendations with us in the comments or on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram (@LanternReview).