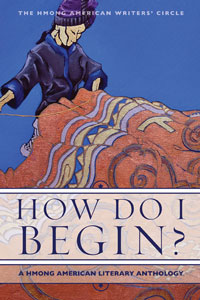

How Do I Begin? A Hmong American Literary Anthology | Heyday 2011 | $16.95

How Do I Begin? A Hmong American Literary Anthology | Heyday 2011 | $16.95

The NY Times began the new year with a piece about the Hmong American Writers’ Circle and the cultural context in which it operates. And our most recent issue of the Lantern Review put a spotlight on HAWC in Community Voices. This is only the beginning of much-deserved attention for this unique generation of new writers.

How Do I Begin is an apt title for an anthology of writers whose ethnic identity is doubly marginalized: though the Hmong roots are in southwest China, most emigrated/fled to the US from places like Laos or Vietnam after the Vietnam-American War. Burlee Vang, in his introduction to the book, describes himself as “born into a people whose written language has long been substituted by an oral tradition.” The written language of the Hmong was lost after assimilation in Imperial China long ago; this is not to mention assimilation into Thai and Lao culture, where most Hmong are provided an education only in their host countries’ official languages. The Hmong language has remnants in traditional embroidery but they have become indecipherable. Writers identifying as Hmong American today, therefore, have the tremendous task not only of writing themselves into history and literature, but also of gathering their names and identities from the pieces available. English is their adopted language, and so these writers must weave a warp and woof through multiple traditions.