Last May, the LR Blog featured the Angel Island poems in our APIA Heritage Month “Poetry in History” series. In the post, Iris explains:

Often called the “Ellis Island of the West,” Angel Island served as the site for processing as many as 175,000 Chinese immigrants from 1910-1940.

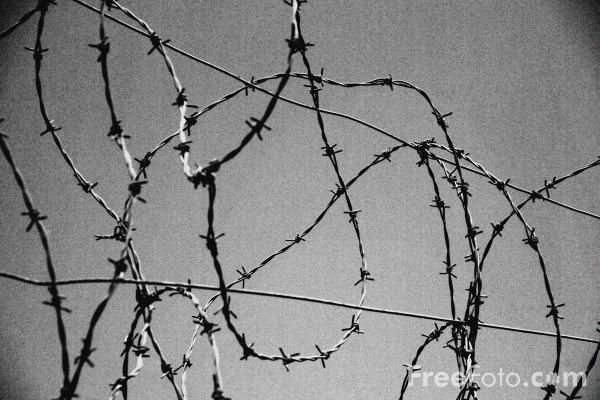

Detainees were separated by gender [and ethnicity!] and locked up in crowded barracks while they awaited questioning, for weeks or months — sometimes, for years — at a time. To pass the time, many immigrants wrote or carved poems into the soft wood of the barrack walls.

The poems vary in theme, form, and in level of polish, and serve as a testimony to the experience of detention, chronicling everything from hope to anger to loneliness, to a sense of adventure.

At the time, I had never visited Angel Island or read any of the poems inscribed on the walls of the immigration station, but last week I made the pilgrimage: flew to San Francisco, drove to Tiburon, took the ferry, made the hike, etc. It was an odd experience—I arrived at the dock at the same time as two groups of fifth grade history students, meaning that I toured the immigration station with them and heard all sorts of hilarious comments: “Who fought who during the Civil War? China and America?” as well as some not-so hilarious ones: “Chinese, Japanese, itchy knees, money please…” a sing-song chant I remember hearing about from the mid-twentieth century, around the time the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed. Amazing, really, what little impact four decades of activism have had on prevailing attitudes about who is/n’t included in “America” and why.

Continue reading “Event Coverage/Weekly Prompt: Angel Island”