A Guest Post by Stephen Hong Sohn, Assistant Professor of English at Stanford University

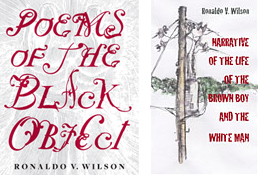

Narrative of the Life of the Brown Boy and the White Manby Ronaldo V. Wilson | U of Pittsburgh Press 2008 | $14

Poems of the Black Objectby Ronaldo V. Wilson | FuturePoem Books 2009 | $15

In this review, I discuss Ronaldo V. Wilson’s Narrative of the Life of the Brown Boy and the White Man (University of Pittsburgh Press 2008) and Poems of the Black Object (FuturePoem Books 2009). Wilson’s first full-length poetry collection might be more specifically described as prose poetry, as implied by its title. There are really no formal line breaks throughout the collection, so one is forced to consider what makes such a work poetry as opposed to prose. This genre-defying work’s title also clearly derives inspiration from two canonical African American literary texts: Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. In Wilson’s title, there isn’t any mention of the word “slave,” but the impulse to explore the conditions of subjection and domination are still very much there. Wilson’s work thus seems to enact a neo-slave “poetic” as derived through the queer racial minority’s subjectivity. The reference to the “brown boy” and the “white man” in the title also helps situate what actually occurs in the prose poetry blocks throughout the collection. “Brown boy” suggests that the lyric “I” is a mixed-race subject and likely an adult, but clearly one who does not have much access to economic resources. He is engaged in a homosexual relationship with “White Man,” someone likely older and with clearly far more money than the “Brown Boy.” Racial difference, class difference, and age difference, among other such distinctions, generate the rubrics of power and domination that mark the tension between “white man” and the “brown boy.” Wilson’s work is raw, dense, and does not shy away from difficult topics, as demonstrated by the following excerpt, which is fairly indicative of the stylistic impulses of the collection:

“Go Shower. This command reveals [the brown boy’s] relationship to the white man. He follows his lover’s orders like a slave without anything but the promise of being fed and shown a movie” (64).