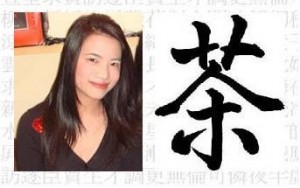

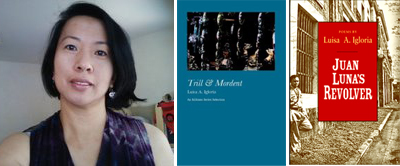

As we continue our exploration of ekphrastic poetry, poet Fiona Sze-Lorrain, whose first book (Water the Moon) we reviewed last month, graciously answers some questions that we’ve posed to her about the ekphrastic elements of her collection.

LR: How do you envision your work with ekphrasis with respect to the larger arc or project of Water the Moon?

FSL: Ekphrasis is indeed one of the many channels I turn to for building the muscle of my imagination. The Greeks say, “In the beginning was the verb.” How about “In the beginning was the image”? I remember having read — a long time ago — an interview with the French theatre artist, Ariane Mnouchkine, who (probably influenced by the Japanese theatre philosopher and pioneer, Zeami) perceived emotion as coming from recognition, which is an useful perspective for actors. In a way or another, I too define my experience of ekphrasis as emotion coming from recognition… for instance, by recognizing something in paintings that can transform descriptive clues to deceptively personal/emotional landscapes or narrative possibilities. Part of the larger arc of Water the Moon is about dialogues with artistic voices or consciousness that follow me like shadows over time. Steichen, Van Gogh, Dora Maar, Man Ray… these happen to be just some of them whose iconic images play a role in molding my sensibilities since a child.

LR: In “Steichen’s Photographs,” you write “Photos have no verbs . . . / . . .Verbs are those trying not to pose” (58). Indeed, it seems that your ekphrastic engagement with photography in the collection is more immediate in nature than your engagement with other artistic media, like painting — for example, in “Van Gogh is Smiling,” you continually invite a reconstruction of his iconic images, “Let’s imagine fifteen sunflowers” or “Let’s retrace your starry blue night” (51), rather than delivering a direct experiential response to a particular work. In what ways does the camera’s eye provide a different type of visual or interpretive experience than other forms of visual art (e.g. painting, sculpture)? How did these differences influence your decisions about craft and perspective?

FSL: Perhaps this is just a personal preference. I am married to a man who knows much about the world and craft of photography. By chance and good fortune, I have also crossed paths with the work of a few important photographers of our times. So I tend to feel more intimate with photographs, though paintings, to be honest, always offer me the contemplative space whenever I need it. Photographs — less so. They tend to be more visceral for me, and contain specific social realities that I can more easily identify with or pinpoint. As you can see, the cover image of my new book of poetry, Water the Moon (italics) is also a photograph. (It is entitled “Cortona,” taken by American photographer, Blake Dieter, in Italy). The clock in it is a metaphor of the Moon – in terms of time. I like films tremendously too and sometimes imagine photographs as immortalised snapshots from an unknown film. In general, it is harder for me to be oblique when writing about photographs than about paintings. You do not see something just because it is visible. There must be something else. What is it? I don’t know.

LR: Both “Steichen’s Photographs” and “Larmes” balance deftly on the seam between the perceived and the perceiver — in other words, we are made aware of the strange subjectivities at work when our gaze as readers is directed towards the speaker, whose observations become the subject of the poem as a piece of art, even while she herself is engaged in a process of fixing another artist’s subject in her own gaze. How can ekphrasis be of use to both the poet and the reader of poetry as an exercise in gaze, perspective, and subjectivity?

FSL: Ekphrasis (like any form of writing) is all about distance, because ultimately even if emotion must come from recognition, there comes a distilled point when the lie of the expression becomes evident: the artist, the painting, the poem, the writer, the reader, the reading … all these can never exist in one same space of subjectivity. “Let it not be the medium we question but the man — painter and photographer,” summed up Sadakichi Hartmann in “A Monologue” that was published in Camera Work in 1904, around the time of Steichen’s early photography. If anything, what ekphrasis offers is a bridge between various agendas, intentions and temporalities, based on an unchanging image. This bridge is dynamic — it constructs and deconstructs itself all the time. Besides, no one gaze is identical. I suppose it really is just simply the evocative power of an image that defines what we would call ekphrasis. At least this is what I feel – for now…

To read more about Fiona Sze-Lorrain, please visit her web site. Water the Moon was released by Marick Press in February 2010 and is available for purchase on their site.