Panax Ginseng is a monthly column by Henry W. Leung exploring the transgressions of linguistic and geographic borders in Asian American literature, especially those which result in hybrid genres, forms, vernaculars, and visions. The column title suggests the congenital borrowings of the English language, deriving from the Greek panax, meaning “all-heal,” and the Cantonese jansam, meaning “man-root.” The troubling image of one’s roots as a panacea will inform the column’s readings of new texts.

*

*

Recently, a colleague explained to me the ubiquity of the subjunctive tense in Spanish, which lends itself well to the magical realism of what-ifs and should-haves inhabited by the speaker. I countered that Chinese has, effectively, no subjunctive tense. I taught bilingual children in Hong Kong some years ago and they would write, for instance: “I wish this poem is good,” and, “If I am a seabird I can enter every apartment window in Hong Kong.” These clauses’ constructions signal no suspension of disbelief. The wish is conjured and, in the next instant, becomes grammatically true. When this nine-year-old imagines herself as a seabird, it is not that she could enter through windows—she already can.

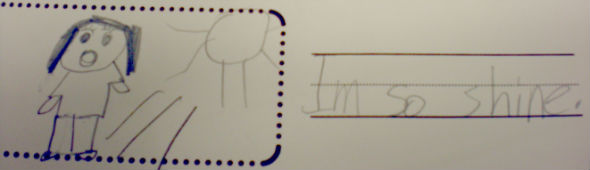

Another of my favorite examples is from a worksheet I gave to a five-year-old. She was directed to draw a picture of herself and use an adjective to describe her mood. She drew herself open-mouthed under the sun and wrote, “Im so shine.” Verbs and adjectives consist of the same words in Chinese and are distinguished only by context or signifiers. That five-year-old’s shiny mood is something which she enacts, rather than something which qualifies her. Continue reading “Panax Ginseng: Introduction”