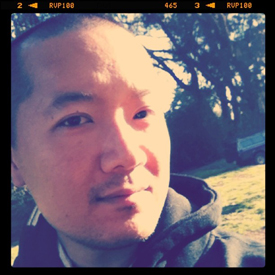

Aimee Suzara is a Filipino-American writer, cultural worker and educator who has been writing and performing in the San Francisco Bay Area since 1999. Her first play, Pagbabalik (Return) was produced in 2006-7 and featured at several Bay Area festivals, and she is developing her second, A History of the Body, both supported by the Zellerbach Arts Fund. Her poems can be found in several journals and anthologies, including Walang Hiya (No Shame): literature taking risks towards liberatory practice, Kartika Review , Konch Magazine, Lantern Review and her chapbook, the space between. She has been a featured poet and educator at schools, universities and arts venues nationally. Suzara has a Mills College M.F.A. and teaches English at Bay Area colleges. She has been a Hedgebrook Resident Artist and will be an Associate Artist at the Atlantic Center for the Arts in 2011.

For APIA Heritage Month 2011, we are revisiting our Process Profile series, in which contemporary Asian American poets discuss their craft, focusing on their process for a single poem from inception to publication. This year, we’ve been asking several Lantern Review contributors whose work gestures back toward history or legacy to discuss their process for composing a poem of theirs that we’ve published. In this installment, Aimee Suzara discusses her poem “My Mother’s Watch,” which appeared in Issue 2 of Lantern Review.

* * *

Though I began writing it in 2008, three years after my parents’ return to the Philippines, this poem began on my first visit “home” in 1991. In the opening moment at the bustling palengke (market), my mother insisted that she keep on her beloved Rolex, despite the attention I felt it drew. Through the poem, I sought to gain empathy for her attachment to the watch and what it symbolized. At this crossroads where goods are sold and money exchanged, the watch became the entry point to my family’s journey as immigrants.

And so I traced back the genesis of this watch—more accurately, the events leading to the desire for the watch. I had been piecing together my parents’ story and was fascinated with their uprooting from the slow-paced life of their childhood, to the full-color Technicolor dream of Kentucky Fried Chicken, Elvis songs and surround-sound systems. I was interested in this proverbial upward mobility, how it swept these newlyweds, not more than a few dollars in tow, into a life of shiny hyper-Americana. We were an unusual Filipino family living up the nuclear-family dream, moving frequently, cut off from anything Pinoy. Racism was thick in the small desert town where I spent much of my childhood, and we were taught not to trust anyone. In the age of credit cards and microwaves, we were right up in it, and at times it seemed we lived on an island stocked, as if our ammunition against the world, with Betamax videos, Jiffy pop and Lean Cuisines.

In peer feedback, it was suggested that this was a poem about privilege and its contradictions. What had been lost, and what could possibly be gained in its place, when a sense of genuine status or acceptance would always be denied? In the attempt to return to our beginnings, what do we cling to? Now came the questions befit for memoir. Was I treating our story with enough compassion? I felt I had to ask permission; my mother read it, and she did not mind my candidness. In the writing of the poem, the roots of my parents’ desire for the “flashy” began to unravel. Images that pushed through marked my parents’ coming of age in America, and then mine.

The first draft of the poem was in three parts, but it was suggested that I separate it into more, that it was too rushed and condensed. This made sense for what I wished to convey about time. The watch, like a heartbeat, like our lives, ticked on its own time. In its final version, in five parts, the poem spans at least twenty-five years. In the remembering, and in the writing, time stands still.

* * *

Excerpt from “My Mother’s Watch”

IV.

They do not yet miss their left-behind lives:

Lolo’s rule in the house with the green metal gate where

nine kids left for the West,one by one by one

movie house in the little town by the sea

popcorn sold out of recycled coffee cans

Sine del Sol burns to the ground:

fatherless tensibling grudges

tsinellas shuf shuf shuffle across aged wooden floors

timemeasured in sunrise and sunset

The ones left behind keep time in slow

tick tock the clocks not turning digital

send us some Tang, cigarettes, M&Ms

medicine, a change of the curtains

From “My Mother’s Watch” | Aimee Suzara | Issue 2, Lantern Review | pp 17-24.

Click here to read the poem in its entirety.