Happy Thursday! A lot of relevant literary news has been making the rounds as of late, so we thought we’d do a quick roundup to keep you up to speed.

2014 Kundiman Prize Deadline Nears

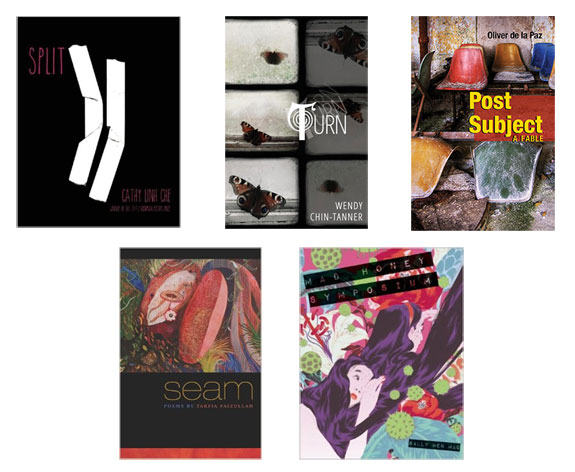

The 2014 Kundiman Book Prize, co-sponsored by Alice James Books, is still accepting manuscripts for consideration until Saturday (3/15). If you’re an Asian American poet who’s been shopping around a full-length poetry manuscript, we encourage you to submit. Past winners have included Janine Oshiro (2010; interviewed on our blog here), Matthew Olzmann (2011; interviewed here), Cathy Linh Che (2012; featured in this Q&A), and Lo Kwa Mei-en (2013). More information, including guidelines, can be found here.

Updates: New and Forthcoming Book Releases by Contributors & Staff

Earlier this year, we previewed a few books that are forthcoming in 2014, and we were recently excited to learn that Tarfia Faizullah’s Seam has now officially been released and that Kristen Eliason’s Picture Dictionary is now available for pre-order on her publisher’s website.

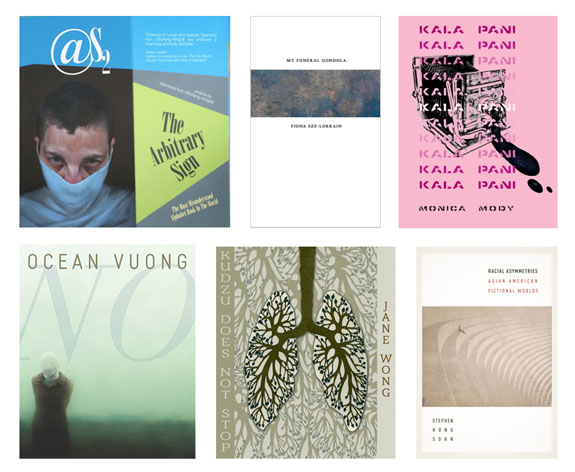

In other contributor publication news, Craig Santos Perez’s third book, from unincorporated territory [guma’], is forthcoming from Omnidawn later this year, and Don Mee Choi’s translation of Kim Hyesoon’s Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream (of which we published an excerpt in Issue 6) was launched at AWP last month. Additionally, Luisa A. Igloria, whose latest collection Henry reviewed here, recently announced that she has two more books forthcoming: Ode to the Heart Smaller than a Pencil Eraser, for which she won the May Swenson Poetry Award, and Night Willow, due out from Phoenicia Publishing (in Montreal) this spring.

New Book of Interest: April Naoko Heck’s A Nuclear Family

Every now and then, we come across a new book that we wonder why we didn’t know about earlier, and this is one of them: April Naoko Heck’s debut collection, A Nuclear Family, which was just released. I [Iris] have been a fan of Heck’s work for some years now, ever since I encountered some of her poems in the first issue of AALR. She writes with clarity and surety, an ear for music, and an eye for lush visual textures, artfully interleaving and building up layers of image to form beautifully collaged, almost dreamlike, poetic landscapes. I was thrilled to learn that she now has a book. (I only wish I had known about it in January when I started putting together our 2014 preview/round-up!)

“The Honey Badgers Don’t Give a Book Tour” Launching This Summer

We were delighted to learn that four of our past contributors (Eugenia Leigh, Sally Wen Mao, Cathy Linh Che, and Michelle Chan Brown) have banded together to do a book tour this summer. Their first stop will be a launch party in NYC (at LouderARTS Bar 13), on July 14th; the remaining tour dates have not yet been announced, but you can follow their website to stay abreast of future developments.

APIA Lit Mag News

A news round-up here wouldn’t be complete without a few updates about recent developments from our colleagues at other APIA literary magazines. One thing is for sure: they’ve been busy.

Last month, Kartika Review released its 2012–2013 anthology (now available for sale on Lulu). Its pages contain work by our very own Mia Ayumi Malhotra and Henry W. Leung, as well as pieces by a number of LR contributors, including Karen An-hwei Lee, Khaty Xiong, Lee Herrick, Michelle Chan Brown, Neil Aitken, Purvi Shah, R. A. Villanueva, Rachelle Cruz, and W. Todd Kaneko.

The AALR also just released its newest issue, themed around the topic of “Local/Express: Asian American Arts and Community in 90s NYC” and guest edited by Curtis Chin, Terry Hong, and Parag Rajendra Khandhar. LR contributors’ work abounds in its pages, as well: R. A. Villanueva, Ocean Vuong, Purvi Shah, Eugenia Leigh, and Cathy Linh Che all have work that appears in the issue.

Last, but not least, TAYO recently launched their fifth issue (which takes “Community” as its theme). They also posted this very thoughtful response to some of the reactions to their revised open submissions policy (in which they will now consider work that is not specifically themed around Filipina/o issues) on their blog. The issues that they address in their post highlight what I think is a very real dilemma for many publications serving specific communities of color: how does one navigate the balance between focusing on being a resource for those within the community while simultaneously remaining relevant within the greater literary conversation—enabling participation from and dialogue with voices from outside the community, as well? It’s a fuzzy line that’s not always easy to walk.

Virtual Reading for APIA Month: Coming Soon

Lantern Review is excited to be participating in a first-of-its-kind virtual reading that will take place this May, in celebration of APIA Heritage Month. Curated by Kenji C. Liu (a past LR contributor and former poetry editor of Kartika Review), the reading will feature contributors from each of several APIA literary magazines, and will take place online in real time—through Google Hangouts. The details of the event are still being worked out, but we will be sure to Tweet and Facebook updates as we know more.

* * *

That’s all we have for you today, but please continue to keep us updated on relevant literary news via Facebook and Twitter so that we can share it—we love hearing what you (and the poets you admire) have been up to!