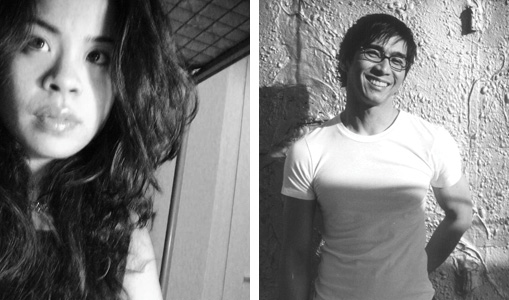

Tamiko Beyer is the author of the award-winning poetry collection We Come Elemental (Alice James Books), and chapbook bough breaks (Meritage Press).

Her poetry has appeared in The Volta, Octopus, DIAGRAM, H_ngm_n, diode, Copper Nickel, The Progressive, and other journals and several anthologies. She is a founding member of Agent 409: a queer, multi-racial writing collective in New York City that performed across the east coast and led workshops at conferences such as the U.S. Social Forum and Split this Rock Poetry Festival.

She has received several fellowships and grants, including a Kundiman fellowship, a grant from the Astraea Lesbian Writers Fund, and an Olin and Chancellor’s Fellowships from Washington University in St. Louis. She was a longtime workshop leader for the New York Writers Coalition.

With a background in communications writing and grassroots organizing, Tamiko has worked for a variety of nonprofit organizations, including the news program Democracy Now!, feminist film distributor Women Make Movies, and San Francisco Women Against Rape. Today, she is the Senior Writer at Corporate Accountability International.

Raised in Tokyo, Japan, Tamiko has lived on both the East and West coasts. She received her B.A. from Fairhaven College at Western Washington University and her M.F.A. from Washington University in St. Louis. She currently lives in Cambridge with her partner, architect Kian Goh.

* * *

LR: Water is the element that is focused on in We Come Elemental, and you have spoken about your interest in the queerness of water. Could you please tell us more about how you envision water as representative of queerness? How does this manifest itself in the book?

TB: Today, just a few days after the Supreme Court struck down the federal “Defense of Marriage” Act, is the last Sunday in June, and New York City is celebrating Gay Pride in all it’s corporatized glory. And [I do mean] it’s.

While I understand and appreciate the many wonderful things about the growing acceptance of gay people by mainstream society in the U.S., I also know that acceptance hinges to a large extent on an idea that gay people are “just like us,” with “us” being (to generalize for sure) white, middle class, heteronormative Americans, coupled with children.

And I’m thinking about how, for me, queerness—well, queer. That is, queerness is: not normative, existing on the exciting and sexy margins of sexuality, constructing radical and meaningful family structures that have little to do with the nuclear family and everything to do with chosen bonds. For me, queerness finds its power in its freakiness. And queerness is everywhere, has always been around, and, as it exists in the margins and applies its critique on the mainstream, is critical to the vitality and vibrancy of humanity. Which is also what makes it so terrifying to so many people.

I’m not sure I would say water represents queerness per se; rather, I find an inherent queerness in the element of water, and particularly in the fluidity of the element. My friend, poet Oliver Bendorf, who also writes a lot about water, described its queerness perfectly: “[I]t shape-shifts, takes on different forms, flows in hardened cracks, expands to fill the space it’s given.”

Water, so soft and smooth, will, in its insistent force, wear away vast canyons. It will freeze into glaciers that last for centuries. It will wash away whole shorelines. It is damn powerful—and its power is sometimes on full display (the crashing waves [of] the ocean, hurricanes and tsunamis), but more often it is barely noticeable, yet pervasive and inescapable. It (or its lack) permeates and affects almost every aspect of our lives—from our environment to the weather to how we nourish and sustain ourselves to how we play. This is how I see the force of queerness reflected in the element of water.

The poems in We Come Elemental are interested in many aspects of water, its queerness and eroticism, its pervasiveness, its ability to both heal and devastate. They also explore the not-so-simple relationship between human power and nature’s power of destruction and creation, in which water plays a key role.