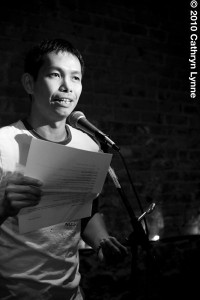

Jenna Le was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, the youngest child of two Vietnam War refugees. She obtained her B.A. in mathematics from Harvard University and her M.D. from Columbia University. Her first book of poetry, Six Rivers, was published by New York Quarterly Books in August 2011. Her poems and translations of French poetry have been published by Barrow Street, The Brooklyn Rail, The Nervous Breakdown, Post Road, The Raintown Review, Salamander, Sycamore Review, and other journals.

***

LR: Many of the poems in Six Rivers riff on classical characters and themes while preserving a conversational use of language. Likewise, you often work in form while eschewing formal language. What do such dualities aim to achieve?

JL: Many of the characters in Greek mythology seem quite real to me, especially the sorceresses like Circe and Medea, who in my mind embody the tragicomic situation of the 21st-century woman who is brimming with intellectual resourcefulness but who is still anguished by her dating troubles. Like, I see Circe as a sort of precursor to Napoleon Dynamite: although she had plenty of “great skills….like nunchuck skills, bow-hunting skills, and computer-hacking skills,” she was still totally hapless when it came to romantic relationships. This is such a thoroughly modern theme that it only makes sense for me to talk about it in colloquial contemporary English.

I use traditional verse forms for much the same reason: because I feel they have a lot of relevance to our modern-day plight. The tanka, for example, is a verse form that was historically used by aristocratic Japanese poets to treat such subject matter as clandestine assignations with illicit lovers. Well, I always thought it would be interesting to repurpose this verse form and use it to address contemporary sexual practices that really don’t differ all that much from ancient ones (“hooking up,” etc.).

LR: There is a strong geographical trope in your book with literal journeys along rivers that are both real and fictional. How do these journeys serve your narrative?

JL: Well, immigration and displacement played big roles in my family history. All the journeys in my book recapitulate that, in a way. And, in a way, it’s this small-scale recapitulation of a large-scale narrative of escape, of striking out on one’s own in an unfamiliar and sometimes hypo-oxygenated territory, that drives the narrative of Six Rivers.