As the summer winds down and the academic year ramps up, here are just a few August and September books by APA poets that we’re excited to crack into.

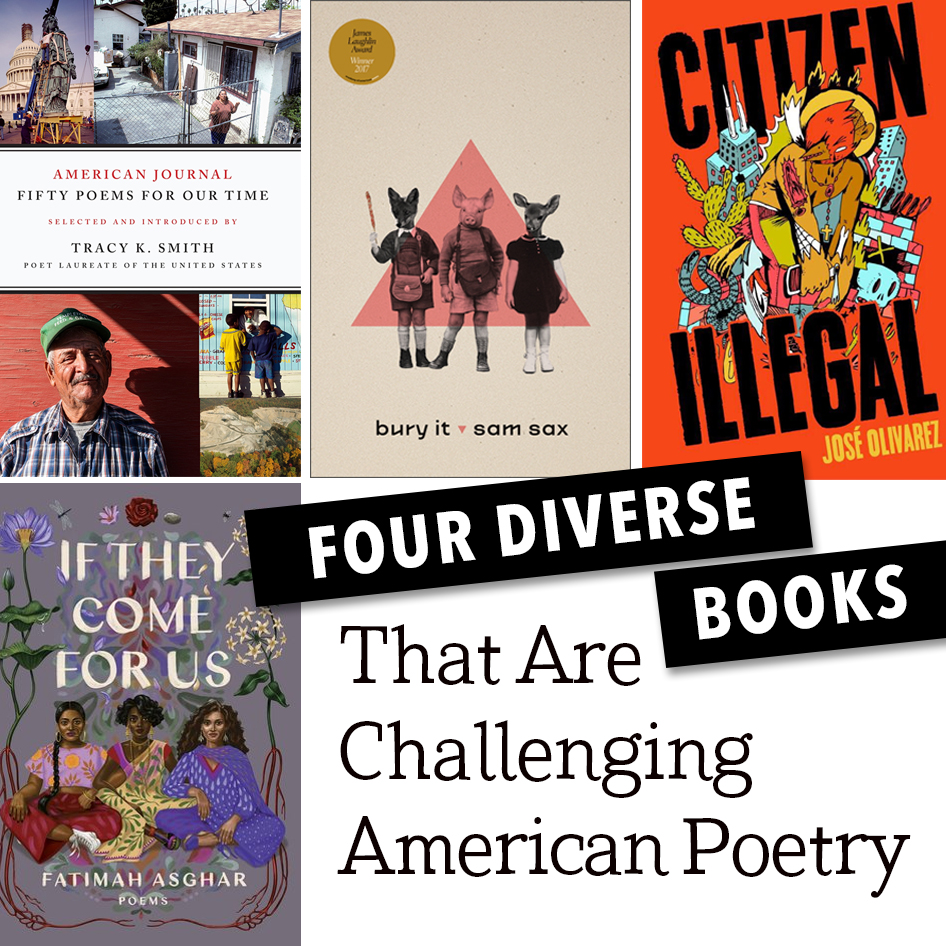

FEATURED PICKS

Kimberly Alidio, : once teeth bones coral : (Belladonna*, Aug 2020)

We were delighted to learn that Issue 2 contributor Kimberly Alidio’s new book, : once teeth bones coral :, is out this month from Belladonna*. Alidio’s deft syntactical and structural play appears to be in full force in this new collection, about which Cheena Marie Lo writes, “Alidio’s poems reveal the ‘luminous familiar,’ traces of the interior that make visible the simultaneity of histories and futures, the possibilities inherent in queer connection, kinship, and refusal. These fragments are precise and expansive, and will resonate for a very long time.”

W. Todd Kaneko, This Is How the Bone Sings (Black Lawrence, Aug 2020)

Another book that we’re excited to see hit shelves this month is two-time contributor W. Todd Kaneko’s This Is How the Bone Sings. Kaneko’s second collection, This Is How the Bone Sings interrogates ancestry and fatherhood through myth, legend, and history, including the poet’s family’s experience in the Minidoka concentration camp during WWII. We’ve long admired the striking imagery and music of Kaneko’s work, and this new book promises to be no exception. (As a bonus, Kaneko’s poem “The Birds Know What They Mean,” which we published in Issue 7.2, appears in the book. If you enjoyed that piece as much as we did, we hope you’ll check out the collection, too!)

Barbara Jane Reyes, Letters to a Young Brown Girl (BOA, Sept 2020)

We’ve been looking forward to Issue 1 contributor Barbara Jane Reyes’s latest collection, a series of epistles addressed to young (especially Filipina/x) women of color, for months now. At a time when mentorship and the importance of literary lineages (especially feminist, WOC lineages) have been top of our minds, Reyes’s book seems especially timely. Writes Asa Drake in her review of the book for Entropy, “These are poems about what we give ourselves, rendered in language to assure the young brown girl writing in America that she is not alone. What is a mixtape if not a love letter that confirms we have all existed in the world, and we have been listening, perhaps together?” This is one love letter that we can’t wait to read.

* * *

MORE NEW AND NOTEWORTHY TITLES

Sumita Chakraborty, Arrow (Alice James, Sep 2020)

Angie Sijun Lou, All We Ask Is You To Be Happy [Chapbook] (Gold Line Press, Aug 2020)

Sachiko Murakami, Render (Arsenal Pulp, Sep 2020)

Jihyun Yun, Some Are Always Hungry (U of Nebraska, Sep 2020)

* * *

What new and notable books are on your reading list this month? Share your recommendations with us in the comments or on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram (@LanternReview).

* * *

ALSO RECOMMENDED

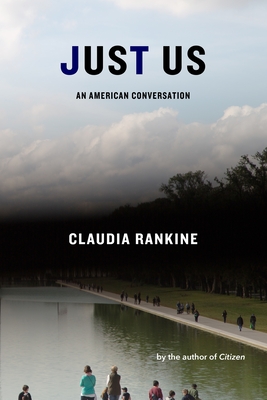

Just Us: An American Conversation by Claudia Rankine (Graywolf, Sep 2020)

Please consider supporting a Black-owned bookstore with your purchase.

As an Asian American–focused publication, Lantern Review is committed to promoting diverse voices within the literary world. In solidarity with the Black community and in an effort to amplify Black voices in poetry, we’re sharing a different book by a Black poet in each of our blog posts this summer.