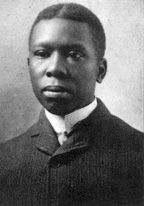

For the poet of color, whose repository of language is often composed of multiple “englishes” (standard English being only one of them), the dialect poem can become a site of great experimentation–and great conflict. Best known in the American canon, at least in terms of dialect poetry, are the works of noted African Americans poets like Paul Laurence Dunbar and later, Langston Hughes with his jazz and blues poetry during the Harlem Renaissance. Dunbar, often considered to be the first African American poet of national eminence, is widely read both for his black vernacular and standard English verse. The marked differences in syntax, register, tone, and even subject matter that distinguish works like “We Wear the Mask” or “Ships That Pass in the Night” from “When Malindy Sings” are fascinating to me, particularly because both “voices” are grounded, I think, in Dunbar’s understanding of himself as an English language/African American poet.

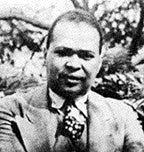

Equally fascinating to me are figures like Countee Cullen, who, like Hughes, was a prominent figure in the Harlem Renaissance, but who (unlike Hughes) vociferously rejected the use of black vernacular in his poetry. Why? Because he considered poetry worth reading to be poetry that was carefully metered, rhymed, and executed in the tradition of Keats and Shelley, his two greatest influences. For a more detailed exploration of Cullen and Hughes’ differing views on questions of racial representation, poetics, and aesthetics, see the comparative essay “Jazz or Junk?” posted on Renaissance Collage. Continue reading “Editors’ Picks: The Art of Writing in Dialect”