In celebration of our magazine’s ten-year anniversary, we’re catching up with past contributors this summer via our process profile series. In today’s profile, Issue 6 contributor Brynn Saito reflects back on her poem “Dinuba, 1959.”

* * *

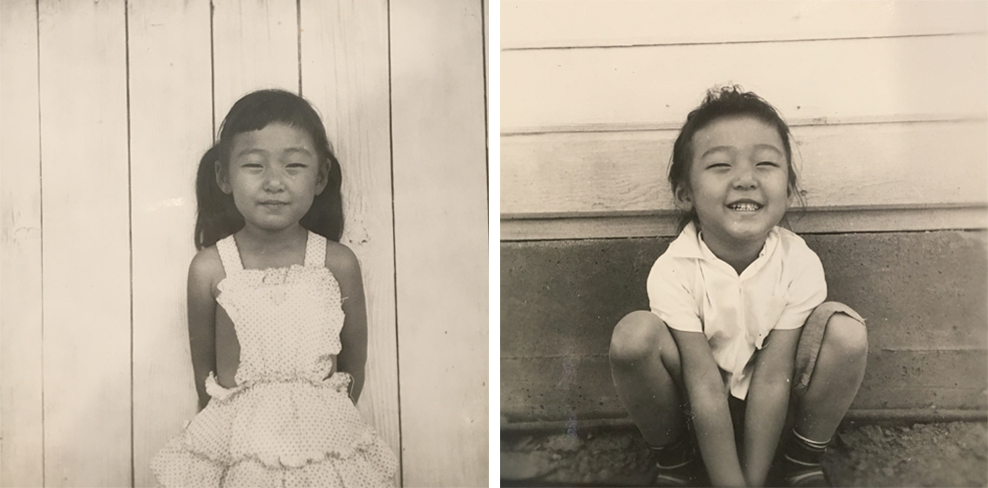

Inspired by communion with a photograph, this short poem inquires into the life and spirit of my mother, Janelle Oh Saito. In the photograph, my mother is about five years old, appearing as the poem describes: bright-eyed before the Dinuba, CA, farmhouse in a white dress. Rereading it now, I see how much my “terrible need to know” has shaped my poetics over the course of the last decade, in the time since the poem manifested itself on the page. In my mother, I’ve forever intuited an unsheltered, untouched wonder—a powerful wonder that tips into joy and laughter so easily. Alongside this energy, I’ve felt a fiery rage, born from what she endured as a child and fueling her current community work. In trying to understand her life, her personhood, I was—I am—subconsciously seeking to know something elemental about myself and something true about the histories shaping our family and making possible the worlds awaiting us. The photograph, then, was a portal to past and future.

I’ve returned, after nearly twenty years away, to my hometown of Fresno, CA, to live. Fresno is the primary city in the middle of the sprawling Central Valley—the valley where my immigrant elders labored; to where my grandparents returned after the Japanese American incarceration of World War II; where my mother’s grandparents settled after fleeing Korea, which, at the turn of the twentieth century, was suffering and surviving under the brutal Japanese occupation. My “terrible need to know,” first articulated in this poem, has, in the short time I’ve been back, unearthed new stories from the memory trove. Closer now to the land that made us and living about a mile from my parents’ house, I’ve become a listener and recorder. (Visit Dear— to see one community-based poetry project that has bloomed into a living archive of letters and portraits.) I’ve also nudged my mother (and father) into writing and telling their own stories, which they’ve performed before large audiences—something I never expected to see.

“I know who she becomes and why,” goes the poem. “But the how will escape me / continues to escape me.” Will, perhaps, always escape me, as our knowledge of the past is forever incomplete. But a desire fills that gap—an imaginative power that drew me to the photograph and draws me still: to the wellspring of memory and feeling, to a place beyond language where I commune with the energies that came before me, where I remember and make whole the body of my future self.

“Dinuba, CA, 1959” was published six years ago in Lantern Review, scrawled (most likely) in a workshop setting, and chiseled down to its three sentences for its inclusion in my second book. Today, it continues to undisguise itself, reveal itself—as the most lasting poems (and people and places) do.

* * *

Brynn Saito is the author of two books of poetry from Red Hen Press: Power Made Us Swoon (2016) and The Palace of Contemplating Departure (2013), winner of the Benjamin Saltman Award and a finalist for the Northern California Book Award. She recently authored the chapbook Dear—, commissioned by Densho, an organization dedicated to sharing the story of the World War II–era incarceration of Japanese Americans. Brynn is assistant professor of creative writing in the English Department at Fresno State and codirector of Yonsei Memory Project. More at brynnsaito.com and yonseimemoryproject.com.

ALSO RECOMMENDED

White Blood by Kiki Petrosino (Sarabande Books, 2017)

Please consider supporting a Black-owned bookstore with your purchase.

As an Asian American-focused publication, Lantern Review is committed to promoting diverse voices within the literary world. In solidarity with the Black community and in an effort to amplify Black voices in poetry, we’ll be sharing a different book by a Black poet in each of our blog posts this summer.