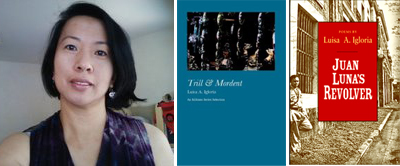

As part of our exploration of ekphrastic poetry, poet Luisa Igloria (who was featured in our November 2009 interview) very graciously agreed to answer some questions about the role that ekphrasis plays in her most recent book, the Ernest Sandeen Prizewinning Juan Luna’s Revolver [UND Press 2009].

LR: In what ways did visual art inform your process in developing Juan Luna as a project?

LI: Visual art provided both a means to stimulate individual poems, as well as provide points of thematic unity between the different parts of the book. I looked at photographs, old lithographic representations, postcards, and more. Juan Luna’s Revolver could not have evolved without calling to poems that make some reference to art — after all, Juan Luna was a painter, one of several Filipino artists and intellectuals who left the Philippine colony for Spain and other European destinations in the mid to late 1800s to study and to travel. Juan Luna was perhaps most famous for his mural “Spoliarium” which depicted two defeated gladiators being dragged into a chamber where they would be stripped of their armor and prepared for burning. The painting won one of two gold medals at a Barcelona exposition and took the art world there by surprise. In truth, however, I came to the Juan Luna poems in the book more gradually — the book perhaps really began with my long-standing fascination with stories about the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, and how 1100+ indigenous Filipinos were transported to serve as live exhibits there (many of them were taken from the northern Cordillera region in the Philippines, which is where I grew up). I’d done considerable research on this and looked at archival material, and it became clearer to me as the poems came that one of the central themes in this project was colonial spectatorship. Fair-goers at St. Louis in 1904 came to see the Philippine reservation and its half-clothed savages, and protested that they had paid to see “the authentic native” when well-meaning persons out of concern for their health, wondered if they should be given warm clothing to wear. While traveling in Europe, Juan Luna and his contemporaries were similarly gawked at. But through the powerful art and literature they produced (Juan Luna’s compatriot Jose Rizal wrote the two novels that further inflamed a grassroots-led revolution which finally overthrew the Spanish colonial regime) they had found a way to return the gaze of the Other.

LR: What influenced your decisions in terms of where and how to place ekphrastic poems like “Letras y Figuras,” “Dolorosa,” and “Mrs. Wilkin Teaches an Igorot the Cakewalk” within the text of Juan Luna? How do you envision their particular contributions to the arc and the rhythm of the text?

LI: When I’m beginning to work on the structure of a book, I also like being led by the tonal and emotional congruencies between parts. I try to see what kinds of “music” might be made by the decision to set one poem next to another, one section next to another. I don’t necessarily think a chronological approach is always the best one. And, I much prefer trying to set up relationships across poems so that it might be possible for an image or motif to jettison the reader back or toward another moment, in another poem… For example, even if the 1904 / World’s Fair poems form the last section, I hope it eventually becomes clear to readers that I’ve been trying to talk about the implications of looking at something or someone, or being held in close scrutiny, really from the very outset (such as in a very early poem in the book like “Intimacy deserves a closer look” ).

LR: In the poem “Ekphrasis,” you write of the viewing of sculpture as a process of critical reading: “the bridle that is history’s wants it to stay / its previous course — At least that’s how // it might be read” (55). In what ways can the exercise of “seeing” and subsequently interpreting a physical object of beauty prove useful to poets in our own crafting of imagery and perspective on the page?

LI: Poets frequently “see” and “interpret” — that is, find ways to move from a physically sensuous validation of the world (“seeing” is part of that) to finding in language the means, the shape, the form in which to express it. “Seeing” has never equated to a “neutral” activity to me. Even when I’m people-watching, I quickly realize I’m making up stories, wondering about the hidden narratives: who’s that old couple in the parking lot? where are they going, what are they thinking, who will they meet? what did they have for breakfast? When the imagination exerts an influence on what’s given, we make art. That’s one of the things that still continually amazes and humbles me – that on the one hand historical reports might say of events in the past, “these things are over, they’re done” — but that on the other hand, poetry can say, let’s look at it again; and what if? So yes there is critical reading, but there is also a sense that meaning can be remade or that a closed door is not necessarily what we think it is. We might think we know everything there is to know about something. But poetry always reminds us of the mystery that remains.

To read more about Luisa Igloria and her work, please visit her web site and blog. Juan Luna’s Revolver is available for purchase from the University of Notre Dame Press.