This week’s prompt is, in large part, inspired by NYC-based Poetic Theater Productions’ call for re-magined versions of classical love sonnets , which I have been mulling over and trying to write into for the last week. Thinking about the challenge of modernizing the themes of a well-known sonnet for a contemporary audience has also gotten me thinking about form, at large, and the ways in which the sonnet itself has been re-shaped and re-envisioned in the contemporary era. While poets writing sonnets still continue to seek out the spirit of traditional form variations (such as the use of iambic pentameter, schemes of rhymes or off-rhymes that imitate the traditional Elizabethan, Italian, or Spencerian sonnets’ patterns, or even the inclusion of a turn, or the limiting of a poem’s length to 14 lines), many endeavor to push the form in new directions. There are many examples of “nontraditional sonnets” that buck the rule, but one of my favorites is Jill McDonough’s Habeas Corpus, where she uses the metered structure of iambs, and rhymes that often fall slant, in order to record, and examine, the narratives of victims of the death penalty in the United States. McDonough’s sonnets are, by design, rubbly, and at times brutal in their pacing. They are woven through with found language drawn from historical documents, and her masterful crafting of the poems that enfold these quotations allows the skeleton of the sonnet form to serve almost like prison bars–the poems and the people whose stories they tell are, at once, made visible by means of the formal “cages” which contain them, and are yet simultaneously engaged in a continual struggle against them.

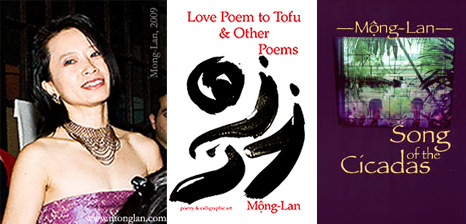

Mông-Lan also employs the sonnet in her collection Song of the Cicadas, whose eponymous sequence is a crown of sonnets, identifiable as such partly because of the length of each section (which falls around 14 lines, on average), but primarily because of its use of the formal convention in which the sonnets are linked by a series of repeated lines (the end line of the previous sonnet becomes the first of the one that follows, and the end line of the final sonnet is the first line of the first). “Song of the Cicadas” breaks from the notion of the sonnet as a formally-regulated structure by disregarding meter and rhyme scheme; its individual sections do not even quite look like sonnets (which we expect to be blockish and dense in shape, and quite short), as the poet’s use of unconventional breaks and spacing causes the poems to float, lattice-like, on the page. And yet, because it operates by calling upon the notion of the sonnet (however much it simultaneously resists it), we, as the reader, can read it as such: songlike, concise, clean and tightly polished, colored by the signature turn or tonal shift that we expect–even assume–drives the argument of each section forward.

Mông-Lan, Jill McDonough, and the many other contemporary poets who play with this well-loved form challenge us to re-think the sonnet, not just in order to “revive” it from the realm of stodgy antiquity or cliché, but in order to re-imagine it as was originally intended–not just as a pretty poetic form, but as a form of confident, and often surprising, poetic argument.

Prompt: Write a sonnet that re-imagines traditional formal constraints while still retaining enough of traditional conventions to make it identifiable as a “sonnet.”

(For more on different types of sonnet forms, please see this page from Poets.org).