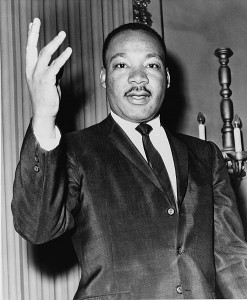

Martin Luther King, Jr. would have been 81 years old today. I wanted to do a prompt this week which engaged thoughtfully (in some way) with his legacy—with the work that he began and which continues today—and so I was pleased to stumble upon Laura Gamache’s lesson plan, “The Right to Inquire” (on the Teachers & Writers Collaborative’s web site), in which she uses poetry as a means to link the questions about equality raised by the Civil Rights Movement with contemporary racial injustice for a group of children two generations removed from MLK’s era. In her three-part exploration, Gamache juxtaposed the big, outspoken rhetoric of the challenges raised in Langston Hughes’ poem, “Let America Be America Again” with the much-quoted rhetoric of Emma Lazarus’s “The New Colossus” and asked her students to write poems that engaged in different ways with questions about the slippery relationship between what we imagine or idealize as “freedom,” and the reality of the matter.

In may ways, I think that Gamache’s title, “The Right to Inquire,” touches a vein at the heart of the struggle for social justice as it continues today. Who has the right to raise difficult questions, or questions that nobody wants to hear? And who will have the courage to do so? In reading Hughes’ poem myself, I was struck not only by the questions that he raises (“Who said the free? Not me? /Surely not me? The millions on relief today? / The millions shot down when we strike? / The millions who have nothing for our pay?”), but also by the broad claims that he lays to the voices of those who (ought to) have the right to freedom, in order to argue that America has not been “itself,” or has not met its own precious standard of liberty, in which the call to equality rings foremost:

“I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart,

I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars.

I am the red man driven from the land,

I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek–

And finding only the same old stupid plan

Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak.I am the young man, full of strength and hope,

Tangled in that ancient endless chain

Of profit, power, gain, of grab the land!

Of grab the gold! Of grab the ways of satisfying need!

Of work the men! Of take the pay!

Of owning everything for one’s own greed!I am the farmer, bondsman to the soil.

I am the worker sold to the machine.

I am the Negro, servant to you all.

I am the people, humble, hungry, mean–

Hungry yet today despite the dream.

Beaten yet today–O, Pioneers!

I am the man who never got ahead,

The poorest worker bartered through the years.”