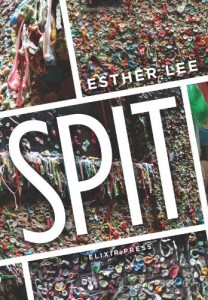

Spit by Esther Lee | Elixir Press 2010 | $16

Spit by Esther Lee | Elixir Press 2010 | $16

What is spit, taken as the title of Esther Lee’s first book of poetry? It can be derogatory, can be DNA and genealogy, can be sustenance and suckling, can be used to form or deform the sounds we make when speaking. The poems in this collection are preoccupied with the mouth, which functions as a site of stagnation just as much as change. The book begins, “When asked if I believe in absolute truths, I cite the lie.” And a few lines down: “Our mouths were stretched to the floor as punishment . . .” In another poem, the mouth is a “rusted hollow,” an irreparably broken car muffler. Later, in “The Real World Is Like This,” the sound of a mother’s “bird-throat” suggests flight, then suggests the clicking sounds of the speaker’s tap shoes driving a rift between her and her sister and, she says, “what my mouth can’t afford.”

Astonishing for a first book, Lee’s signature style is instantly recognizable by the accent she creates visually on the page. The front dedication to her family reads: “I kiss one hundred time[ ].” Generally brackets tell of absence, which can mean revision, loss, or a truncated excess—and in these poems refer to text as much as to personal experience. In the dedication, it is a nod to her parents’ accent. In the “Interview with My [C]orean Father” poems, the bracketed “C” reclaims and reshapes an ethnic label. It also points out how arbitrary are such naming practices, since Corean and Korean sound identical. In “We Are the Happiest Children in the World” and “Ivan / Ivan,” brackets proliferate lines to evoke at once caesura and transition, as we see in:

I tell you I am here mingled [ ] with snow

yellow-white as the page [ ] I suckled from

my grandmother—strange mother—and I [ ] grew

These brackets have a distinct flavor from backslashes, m-dashes, and ellipses; they are a ligature of grammatical pedantry (showing Lee in command of the language) and ungrammatical familiarity (an intuitive, poetic experimentation). They are a punctuation that Lee has made uniquely her own in these poems. Continue reading “Review: Esther Lee’s SPIT”