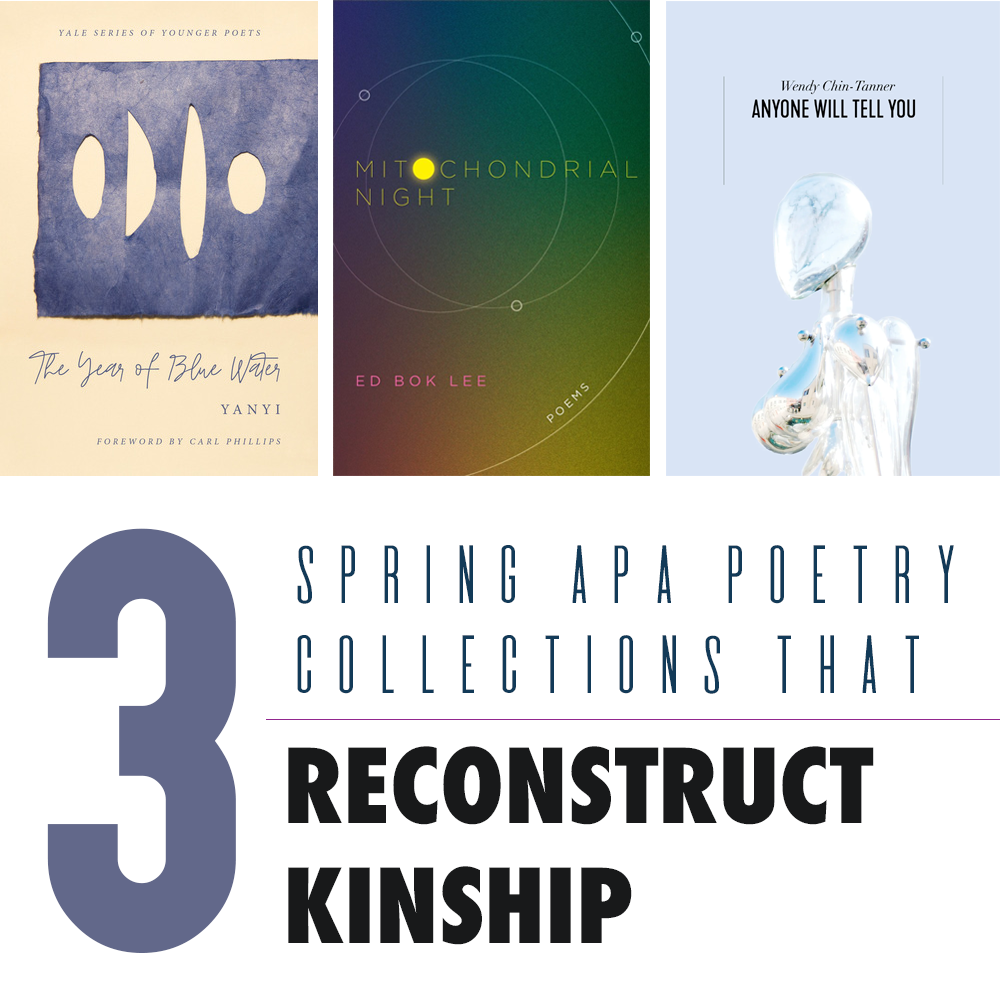

This month’s poetry round-up features three collections that consider and reconstruct restrictive notions of family, kinship, and relationships. Whether through essayistic reflection, dialogue, or lullaby, the poems from these new works scrutinize the power structures that normalize destructive ways of relating to one another while holding dear the people who can see us with clarity and compassion. We hope these books shed light on the people in your lives who enable transformation, as well as on the poetic techniques that can bear witness to intimacy.

* * *

The Year of Blue Water by Yanyi (Yale University Press, 2019)

“I thought that having myself was not supposed to take any effort” (31), writes Yanyi in one passage of The Year of Blue Water. Like many of the passages in the collection, this paragraph is arranged in the center of a page, as though the speaker himself stands in the middle of a hushed room, addressing his listener candidly. This tender dialogue is essential to the speaker’s transformation throughout the collection. “I have no control of my family,” the speaker writes. “They may leave me; I accept that.” What continues despite of (or rather, because of) the pain and violence of rejection is the project of reconstructing self and identity—possible only because of the constellation of chosen kin in literature and life who can, and will, listen and respond to the speaker.

The difficult transformation at the heart of Year of Blue Water honors bell hooks’s redefinition of love—as “an action rather than a feeling”—in order to emphasize, assume, and honor the accountability and responsibility required of love. For this reason, there is an enchanting affinity between The Year of Blue Water and Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights. Just as Gay commits himself each day to finding a “new delight” to discover, exercising his “delight muscles,” Yanyi commits himself to a type of love that recognizes the intentional activity and labor necessary for loving. Love as feeling, as bell hooks has written, has often been “the stuff of fantasy”; if being queer, trans, and Asian only heightens the incongruity of fantasy and reality, then the action of love must always depend on the act of seeing self and other clearly. The concision of Yanyi’s craft paradoxically speaks to how clarity is a process rather than a state to be achieved—each terse sentence builds on the one before, layering meaning upon meaning. “I am worth the work of transformations,” Yanyi writes. “As in, I do not fear how I will emerge from myself, or how many times” (57).

Mitochondrial Night by Ed Bok Lee (Coffee House Press, 2019)

It seems passé to place Ed Bok Lee’s recent collection within the lineage of travel writing, a genre that by now has been exposed and condemned for its often imperialist and colonialist ambitions. But the literary history of travel writing is also full of spectacular and critical turns, thanks to work by Monique Truong, Bani Amor, and Karen Tei Yamashita, among others, that confronts the legacies of empire, decolonizes tourism, and repurposes the genre to gather up communities forcibly split and scattered.

Mitochondrial Night is a dazzling continuation of this project. In “Metaphormosis,” for instance, the speaker’s mother describes traditional harvesting techniques “not of Korea, or Corea, or North Korea, but Chosun” (5); like the shifts in names and borders for Myanmar or Czechia, this story becomes a journey through kingdoms and imperial transitions that “forced a hiccup in my mother’s recollection” (5). Everyday details, as well as familial lineage, serve as carriages for travel—an “aluminum soda can” (57), “A distant Amtrak” (60), “your thumbnail” (81) are all opportunities to reflect on interconnectedness through sustainable exploration. We need

Anyone Will Tell You by Wendy Chin-Tanner, (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2019)

Former LR staff writer Wendy Chin-Tanner’s Anyone Will Tell You is a strikingly musical and melancholic collection that makes much with very little. Many of the poems are careful arrangements of two or three words in each line—a sparse form that Chin-Tanner developed after the birth of her second child. The direct and dynamic relationship between life and art, child and parent, is central to the project of this collection.

For instance, “Index” unravels in fits and starts, line by line: “I confess // I hungered,” the speaker tells us, before recalling, “wait this is // a poem” (14). Interruptions like these force the question: What is a poem, and who holds power over this definition? These questions prove crucial when a pivotal confession arrives several lines later:

“wait I should

say how I

tried to have

another

and it died” (15).

In the context of the emotional turmoil and the social stigma surrounding miscarriage, infertility, and the female body, Chin-Tanner’s poetry reveals its power as an aesthetic object. As a stunning site of stuttered rewording, Anyone Will Tell You rephrases the alternately devastating and wondrous experiences between self and other that have been scripted by and made unintelligible by exclusionary norms. In Chin-Tanner’s lyrical recursions, silence reemerges into language that holds, rather than abolishes, the unpredictable experiences of self and body. As she writes, “all i could do was make / my eyes see and not blink, and not look away” (30).

* * *

What poetry collections have shed light on or transformed your relationships with loved ones? Share them with us in the comments or let us know onTwitter, Facebook, or Instagram (@LanternReview).